Helping Consumers Eat Less

Food companies can help consumers better control their food intake through portion-control packaging, labeling, and product reformulation.

Food companies have been accused of contributing to the growing problem of obesity in the United States (Brownell and Horgen, 2004). They are in a sensitive position because they are torn between two groups of stakeholders—consumers who want a variety of tasty, inexpensive, convenient food, and concerned public policy officials and activists who believe that companies should be more responsive in helping combat obesity.

What causes us to gain weight in the first place is the same three things that enabled our Paleolithic relatives to gain weight and survive the Ice Age—we are wired to overeat food that is convenient, palatable, and easy (inexpensive) to obtain. And we don’t become obese overnight. Slightly more than 85% of the population gain weight because of an average calorie excess of less than 25 calories/day. Yet 25 extra calories/day can gradually become a big problem over the long run. Such gradual problems seldom have instant solutions. There are, however, reasonable steps that can be taken to help turn back the tide a few calories at a time.

Successful food companies and marketers have become successful because they have been able to create win-win situations for both themselves and consumers. They have been able to create foods and delivery systems that profitably satisfied what consumers wanted or needed. There is no reason to believe that addressing the obesity issue will be different. Having the motivation to profitably address this issue will produce some of the same ingenious, innovative solutions as it has in the past.

Unchangeable Human Behavior

A number of contributing factors have made us a more obese culture than we were 100 years ago. Automobiles, computers, cable TV, video games, remote controls, the Internet, and omnipresent convenience stores have all contributed to our obesity. In addition, food-related companies have made it easier and more efficient for us to do our “hunting and gathering.” Basically, companies have followed three key principles that have helped motivate our hunting and gathering efforts (Wansink, 2006):

• Consumers Seek Convenience. Innovations throughout time have generally evolved around reducing the amount of effort it took to move, to learn, or to communicate. Such innovations respectively gave us the wheel, the printing press, and the telephone. Yet these same three motivations also explain why new houses have attached garages with garage door openers, and why ice makers and dishwashing machines are never de-installed. They also explain why driving is often preferred over walking or biking for short trips.

This desire to follow the path of least effort results in a number of changes to our food distribution system that are market-driven but which also make the environment fat-friendly for consumers with weak willpower. Because of this, we get convenient, easy-to-open (and consume) packaging, a wide distribution of vending machines, and fast-food restaurants on convenient corners. We get the chance to buy foods instead of having to prepare them.

• Consumers Seek Variety and Choice. Because we seek variety and choice, we get brand extensions and new flavors. Our desire for variety can motivate new product innovations that include healthy alternatives that we can choose to adopt or to avoid. Some of these alternatives evolve into products that are well-accepted and embraced, such as Diet Coke. Others, such as McDonald’s ill-fated McLean Deluxe hamburger or Hershey’s Taste Sensations candy, are not widely embraced regardless of their healthy twist.

• Consumers Seek (the Option of) Value. With millions of purchases every day, the trade-off of quantity over quality appears to be frequently made. Right or wrong, this contributes to why Wal-Mart generates more revenue than Macy’s. Most people know which establishment sells higher-quality merchandise, but many define value in a way that influences where they shop. Furthermore, although they might not always prefer the less-expensive option, they still want it to exist.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

The food-related company that provides the most value—the most quantity and quality for the dollar—is rewarded with patronage and repurchase behavior by people who prefer it over a competitor who perhaps offers less value. Whether in the grocery store or in the restaurant, bundling meals together (a burger, fries, and a soda) is often a much less expensive than buying the three items separately. Although a food company might be able to encourage people to eat less if it made its food more expensive (either by raising prices or by decreasing portions), this would be foolish. It would disproportionately penalize lower-income consumers and, unless all firms simultaneously did this, would simply drive consumers across the street to a competitor.

It is important to realize that these three principles—convenience, variety, and value—have driven our hunting and gathering tendencies for generations. Knowing this provides us with an idea of what is realistic to recommend and what would be ineffective because of the basic nature of consumers.

Profitably Reversing the Drivers of Obesity

These principles can lead us to overeat, but they can also be used to help us more mindfully eat less. Most of the leading packaged goods companies—like PepsiCo, Kraft, and General Mills—are experimenting with new ideas, programs, and products that they think will be win-win solutions for them and their consumers. Let’s look at what else a sharp, nutrition-conscious marketer could do to profitably offer us food that can mindfully help us lose weight, i.e., profitably help “de-market” obesity. The philosophy behind de-marketing obesity is that there are protable ways that industry can help consumers better control their intake (Wansink and Huckabee, 2005).

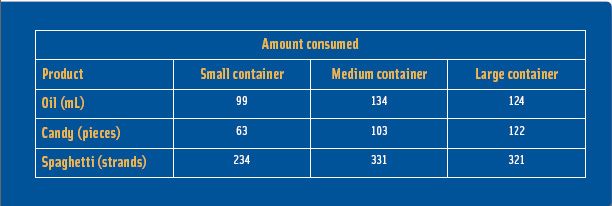

• Think Extra-Small and Extra-Large. From 1970 to 2000, the number of new larger-size packages increased ten-fold (Young, 2005). Food companies super-size for two reasons: to satisfy our demand for value, and to match the competition (Young and Nestle, 2002; Rolls et al., 2004). A large number of us want to be able to buy a lot of food for very little money. If only one restaurant provided a supersized value-meal, it would catch both our attention and our $3.59. If the competitor across the street did not quickly do the same, it could start closing up shop.

In 1996, my laboratory began experimenting with mini-size packs to determine how they would influence how much consumers paid for them and how much they ate (Wansink, 1996). We found that a sizable percentage of people were willing to pay more for something that would help them control their portions and that it would help 70% of these people eat less in a single sitting. Although the packages would be more expensive per ounce than the larger packages, some people would not mind paying more to eat less or to eat better. Given the $43 billion spent on diet foods and weight loss programs each week, this is probably a big group of people.

Does this mean abandoning the value-priced supersize packages in favor of little boutique-sized portion packs? Absolutely not. There may be sizable markets for both—one that wants value and one that wants portion control. The introduction of either into the market would not only give more options to current fans, but also give others (either the price-sensitive or the portion-sensitive) a reason to come back to the fold.

2. Create Packages with Pause Points. In one study (Wansink et al., 2006) moving a candy dish six feet away led participants to eat half as much as when it was close by. They said this was because that distance gave them time to “pause” and ask themselves whether they were really that hungry. In the same way, building pause points into packaging can give people a chance to catch their breath and ask themselves if they really want to continue eating.

This can be done by separating a large container into several smaller containers. It can also be done through the use of internal sleeves that force us to actively decide whether we want to continue eating after we polish o- a sleeve of six (or however many) cookies. Girl Scouts Thin Mints cookies have a built-in stopping point. Instead of being packaged in a wide-open, no-serving-size-limit tray, they are carefully wrapped in two cellophane sleeves. As much as you might want to overeat, when you hit the bottom of that first sleeve, it gives you pause. That is about all most of us need to stop. Another version of this is individually packaged cookies.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

These pause points can also take other forms. In another study (Wansink, 2006) we took canisters of Pringles potato crisps and dyed every 7th chip red, took other canisters and dyed every 14th chip red, and left other canisters plain, with no red chips. We then invited 150 people to watch a video and enjoy the new version of chips. Those who ate from the canisters with no red chips ate an average of 23 chips; those who ate from the canisters where every 14th chip was red ate an average of 15 chips; and those who ate from the canisters where every 7th chip was red ate an average of 10 chips. Having something, almost anything, to interrupt our eating gives us the chance to decide if we want to continue.

This can open a bigger market to sell multi-packs with smaller individual servings. For instance, instead of selling a large 20-oz bag of potato chips, the bag could contain four 5-oz sleeves. In this way, there would be a natural point at which to pause and decide whether we want to continue eating. In another study (Wansink, 2006), we gave 124 students a large zip-lock bag containing either 200 M&Ms or 10 smaller zip-lock bags each containing 20 M&Ms. Those with the large single bag ate an average of 73 M&Ms during an hour, while those with the smaller bags ate an average of 42. Not a big deal? That is 112 calories less—the mindless margin. This is the beauty of various snack food companies’ repackaging their products into 100-calorie packs.

This can open a bigger market to sell multi-packs with smaller individual servings. For instance, instead of selling a large 20-oz bag of potato chips, the bag could contain four 5-oz sleeves. In this way, there would be a natural point at which to pause and decide whether we want to continue eating. In another study (Wansink, 2006), we gave 124 students a large zip-lock bag containing either 200 M&Ms or 10 smaller zip-lock bags each containing 20 M&Ms. Those with the large single bag ate an average of 73 M&Ms during an hour, while those with the smaller bags ate an average of 42. Not a big deal? That is 112 calories less—the mindless margin. This is the beauty of various snack food companies’ repackaging their products into 100-calorie packs.

3. Change the Recipe, But Keep It Good. Since the failure of McDonald’s’ McLean Deluxe sandwich in 1996, food marketers across the U.S. and beyond have taken the wrong lesson away. It was not that there was no market for healthy foods or that companies just cannot make good low-fat products. It was that these foods were typically new products that tasted new, were advertised as new, and were expected by consumers to be bad-tasting because they were “healthy” (Wansink and Park, 2002).

In contrast to this approach, companies could quietly alter existing products in modest ways that reduce calorie density. In this way, there would be no negative taste expectations of a healthy food that would prevent it from getting a fair shot. We call these silent changes “stealth modifications.”

Small modifcations in formulations can lead to reduced-calorie foods like candy bars that are the same size as regular candy bars. High-energy-density items, such as those with a lot of fat, can be replaced with fruits and vegetables without our even being aware of it. McDonald’s offers the option of an apple snack with a Happy Meal, and Wendy’s offers a small salad for the same price as French fries.

Small modifcations in formulations can lead to reduced-calorie foods like candy bars that are the same size as regular candy bars. High-energy-density items, such as those with a lot of fat, can be replaced with fruits and vegetables without our even being aware of it. McDonald’s offers the option of an apple snack with a Happy Meal, and Wendy’s offers a small salad for the same price as French fries.

In general, we tend to look at the size of something as an indicator of whether it is a good “value”—i.e., the bigger the food, the better the value. While adding water, or air, or filler may do little to the taste, it helps maintain the perception of value, and it decreases calorie levels. Even if such efforts only reduce calorie levels by 10%, this decrease in daily calorie consumption would either slow or reverse the weight gain among most of us. However, this would be a slow pound-by-pound reduction, just as gaining was a pound-by-pound process.

Here are three facts about slightly modified and reformulated foods: when the calorie density of a food is decreased, we eat the same volume we usually do, we think we are just as full, and we think the food tastes the same, as long as it hasn’t been labeled as being “reduced calorie.”

4. Provide Simple But Realistic Labels. “Education” is the one-word, easy answer to anything related to health. Once we say “education,” it becomes somebody else’s problem, like the government’s or industry’s. And if their “education” efforts don’t work, the answer is to do more of it.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Marketing nutrition is a noble enterprise, but it is very clear that education, as defined by most, is not the answer. We are either too busy or distracted to read packages, or too preoccupied or hungry to care that we should eat a carrot stick rather than a handful of Wheat Thins.

Clearly labeling calories and serving sizes is a good idea. But we need to be realistic regarding how much of an impact it will have on nutrition. Most research shows that, outside of an artificial laboratory situation, this labeling only influences a modest percentage of consumers. Still, it is worth having.

The question is where should this information stop. The more that is given, the more there a risk of unmerited “health halos” or of the label backring (Wansink and Chandon, 2006). A Food and Drug Administration–sponsored committee on the issue of away-from-home labeling of food recommended that companies should stick to calories, the one common denominator most commonly understood.

The question is where should this information stop. The more that is given, the more there a risk of unmerited “health halos” or of the label backring (Wansink and Chandon, 2006). A Food and Drug Administration–sponsored committee on the issue of away-from-home labeling of food recommended that companies should stick to calories, the one common denominator most commonly understood.

5. Keep it Affordable. Generally, when prices go up, consumption goes down. This is true with meat and potatoes, but not as true with tempting foods, like candy, cookies, and ice cream. Within a reasonable range, when the price goes up, we either buy the candy, cookie, or ice cream anyway because it is indulgent, or we simply switch to another brand.

One of our lab’s pilot studies (Wansink, 2006) showed that increasing the price of selected vending machine candy caused people to buy less of that candy. In the real world, if the price of a candy bar went up by 25 cents, people would either pay it, or they would buy another brand. They would not stop eating candy.

What is certain is that large increases in food prices make us look for other alternatives. It does not mean that we look for healthier options. It does not change our food desires, it just changes where we would go to buy our French fries and candy bars. Raising prices within a reasonable free-market range does not change behavior, it penalizes the people with the least money. It would be a return to rationing for many of them.

The challenge will be to help make the healthier options more attractive and more affordable. We cannot legislate or tax people into eating Brussels sprouts. That is not to say that a smart, well-intentioned marketer can’t convince them to do so.

21st Century Marketing

The 19th century has been called the Century of Hygiene—more lives were saved or extended by an improved understanding of hygiene and public health than by any other single cause. We learned that rats were not house pets and that it is a good idea to wash hands before surgery.

The 20th century was the Century of Medicine. Vaccines, antibiotics, transfusions, and chemotherapy all helped to contribute to longer, healthier lives. In 1900, the life expectancy of an American was 49 years; in 2000, it was 77 years.

Will the 21st century be the Century of Behavior Change? Sure, medicine is still making fundamental discoveries that can extend lives, but changing everyday, long-term behavior is the key to adding years and quality to our lives. This will involve reducing risky behavior and making changes in exercise and nutrition. The more we exercise and the better we eat, the longer and more productively we will live. There is not a prescription that can be written for such behavior. Eating better and exercising more are decisions we need to be motivated to make.

When it comes to contributing most to the life span and quality of life in the next several generations, marketers could be well suited to effectively help us make the move. They are in a good position to develop the products that make it easier to exercise or eat more nutritiously. They can also motivate us to get both of these done. Our eating habits would be a good place for them to start.

by Brain Wansink, Ph.D., is Professor and Director, Cornell food and Brand Laboratory, 109-111 Warren Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853. Portions of this article have been adapted from the author's book, Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think (Bantam, 2006).

References

Rolls, B.J., Roe, L.S., Kral, T.V., Meengs, J.S., and Wall, D.E. 2004. Increasing the portion size of a packaged snack increases energy intake in men and women. Appetite 42(1): 63-69.

Wansink, B. 1996. Can package size accelerate usage volume? J. Mktg. 60(3): 1-14.

Wansink, B. 2006. “Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think.” Bantam Dell, New York.

Wansink, B. and Chandon, P. 2006. Can “low-fat” nutrition labels lead to obesity? J. Mktg. Res. 43: 605-617.

Wansink, B. and Huckabee, M. 2005. De-marketing obesity. Calif. Mgmt. Rev. 47: 4, 6-18.

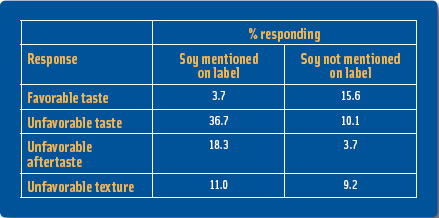

Wansink, B. and Park, S-B. 2002. Sensory suggestiveness and labeling: Do soy labels bias taste? J. Sensory Studies 17: 483-491.

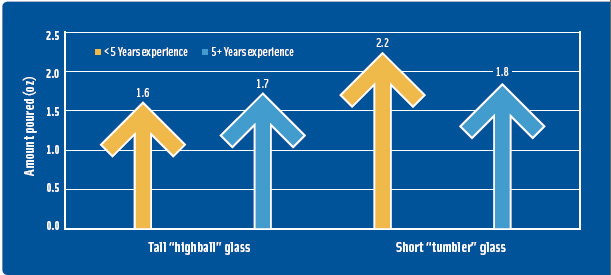

Wansink, B. and van Ittersum, K. 2005. Shape of glass and amount of alcohol poured: Comparative study of e-ect of practice and concentration. Brit. Med. J. 331: 1512-1514.

Wansink, B., Painter, J.M., and van Ittersum, K. 2001. Descriptive menu labels’ e-ect on sales. Cornell Hotel Restaurant Admin. Quarterly 42(6): 68-72.

Wansink, B., Painter, J.E., and Lee, Y-K. 2006. The o�0;0;0;0;0;0;0;0;0;0;0;0;0;0;0;0;0;0;0;1C;ce candy dish: Proximity’s in uence on estimated and actual candy consumption, Intl. J. Obesity 30: 871-875.

Young, L.R. 2005. “The Portion Teller.” Broadway Books, New York.

Young, L.R. and Nestle, M. 2002. The contribution of expanding portion sizes to the US obesity epidemic. Am. J. Public Health 92: 246-249.