Making Sense of Health Claim Regulations

Obtaining regulatory approval for a food or beverage claim is not a simple matter, but it can pay major dividends in the marketplace.

Making a health claim on a food or beverage product can provide consumers with a powerful purchase incentive—which gives manufacturers a strong motivation to obtain regulatory approval for such a claim. But petitioning for a claim is a complicated, time-consuming process without a guarantee of success. And if you think that navigating the regulatory maze in the United States is a daunting prospect, well, it’s a slam dunk compared with attempting to get the nod for a health claim on a product sold in the European marketplace.

To glean insights into key issues about health claims labeling—and numerous other topics—IFT organizers gathered a group of experts for a Food Technology Presents conference themed “Developing and Marketing Products for Consumer Health and Wellness.” The event was held Feb. 27-28 in Chicago. Here’s a look at what some of the assembled authorities had to say about health claims, with a particular emphasis on qualified health claims, plus an update on the challenging process of securing a health claim for a product marketed in Europe.

A health claim, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, “describes a relationship between a food, food component, or dietary supplement ingredient and reducing risk of a disease or disease-related condition.” A health claim is categorized as “unqualified,” which means that its validity is supported by “significant scientific agreement,” or “qualified,” if the evidence that supports it is more limited and “not well enough established to meet the significant scientific agreement standard,” as FDA explains on its Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) Web site (www.cfsan.fda.gov).

Compelling Documentation Required

Food Technology Presents speaker Guy Johnson, a nutritional/regulatory issues consultant, described the scientific evidence required for unqualified health claims in this way. “This is a very, very high standard and requires a significant regulatory process to get there,” said Johnson, President of Johnson Nutrition Solutions LLC, Kalamazoo, Mich. “Unless you have something [scientific documentation] that’s incredible, don’t even think about an unqualified claim,” said Johnson. “It’s going to be very difficult to get.”

Not that securing a qualified claim is a simple matter. “It’s not something that you can do over the weekend,” Johnson observed wryly. “It takes some time and some resources.”

A qualified health claim is an appropriate vehicle for presenting what FDA describes as “emerging evidence” of a substance’s ability to reduce disease risk. Johnson explained that qualified health claims, for which FDA spelled out parameters in its 2003 Consumer Health Information for Better Nutrition Initiative document, originated as a result of a lawsuit filed against FDA. Eventually, Johnson said, an appeals court ruled that if a claim is supported by an adequate level of science, a qualified health claim should be permitted.

“Qualified health claims weren’t exactly FDA’s idea,” Johnson said. “They had qualified health claims foisted on them basically through a court decision.”

--- PAGE BREAK ---

With a qualified health claim, FDA exercises what is termed “enforcement discretion” vs proceeding to the rulemaking involved in approving an unqualified claim, said conference speaker Anthony Pavel, a food law attorney in the Washington, D.C., office of the firm K&L Gates. FDA may choose to act on a qualified claim in the future, continued Pavel, but for the present, the agency’s stance with such a claim is “we’re going to leave you be.”

“There are about 24 qualified health claims that have been cleared and about 24 or 25 that haven’t,” Pavel said. (This total includes claims that relate to foods, beverages, and dietary supplements.)

Among the qualified health claims that have been approved for conventional foods are claims that relate to nuts and reduced risk of heart disease, omega-3 fatty acids and heart disease, and monounsaturated fatty acids from olive oil and heart disease. For a complete list, go to http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/lab-qhc.html.

Qualified health claims have come under fire in some quarters, but Johnson defends them. “FDA has been whacked by certain consumer groups and others for qualified health claims, saying that it’s watered-down science and so forth,” said Johnson. “I personally think qualified health claims are a wonderful thing, but not everybody does. I think they can be very useful tools to communicate information to consumers.”

What’s more he adds, “They’ve been getting approved more [frequently] lately than unqualified health claims.” In addition, the timetable for obtaining a qualified health claim—at least in theory—is shorter than for one that is unqualified.

Going for a Claim

The process for obtaining either an unqualified or a qualified health claim begins with a petition submitted to FDA.

For a qualified claim, “theoretically, within 270 days, they [FDA] are supposed to tell you what the outcome is,” Johnson said. “If they allow the claim, they post a letter on their Web site. It explains very clearly what they have agreed to permit and not permit.”

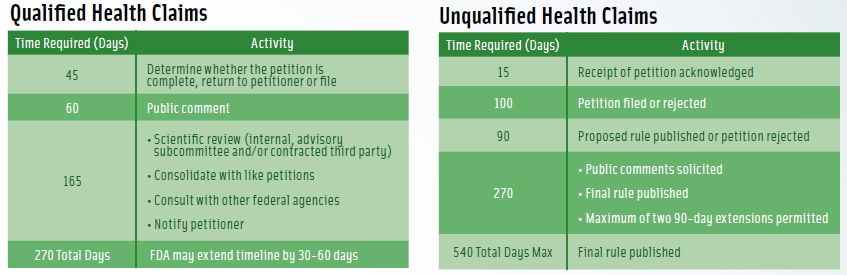

The timetable for an unqualified health claim is twice as long—540 days, but there are no guarantees that either process will be completed on schedule, Johnson said. (See Figure 1 for a comparison of the petition processes, including timetables, for unqualified and qualified health claims.)

After a petition has been submitted, FDA officials undertake a stringent evaluation of the scientific evidence submitted in support of the claim. The process of reviewing the evidence includes the following steps, according to Barbara Schneeman, Director of CFSAN’s Office of Nutrition, Labeling, and Dietary Supplements and also a conference speaker.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Define the substance/disease relationship.

• Identify relevant studies.

• Classify the studies.

• Rate studies for quality.

• Rate for strength of the body of evidence: quantity, quality, consistency, relevance.

• Report “rank.”

Johnson offered his perspective on FDA’s scientific evaluation process. “What you quickly learn in terms of health claim substantiation,” said Johnson, “is the only things that really count from a practical standpoint are randomized controlled trials. Epidemiological information is nice, but if you’re going to go with a straight epidemiological study [in which the data suggest an association between a substance and reduced risk of disease in a large, general population], you’re not going to get a very high level claim.”

Studies used to support health claim petitions need to be done on groups of healthy people who reflect the U.S. population segment that is the target of the claim. For example, said Johnson, a study that seeks to determine if a substance plays a role in reducing the risk of a heart attack among cardiovascular patients isn’t appropriate for use in a health claim petition because it doesn’t indicate the role that the substance would play in a normal, healthy population.

Health claim approval also is limited, according to Johnson, by the fact that studies in support of a health claim must use an FDA-approved biomarker (i.e. a biological indicator of a medical condition), and the list of such biomarkers is not long. Among the biomarkers on the FDA “short list” are total cholesterol level, LDL-cholesterol level, and blood pressure.

Thus, said Johnson, “most of the health claims out there tend to be cardiovascular disease claims,” because most of the approved biomarkers are indicators of cardiovascular health. Health claims that relate to cancer risk reduction are “tough because the only biomarker that FDA accepts is polyp reoccurrence,” Johnson said.

The consultant cited the example of the carotenoid pigment lycopene, which, according to many epidemiological studies, is linked to reduced risk of prostate cancer. “FDA says, well, that’s all very nice, but it’s an association,” Johnson observed. “It doesn’t prove cause and effect ... Give us the randomized clinical trials with the hard clinical endpoint … and then we’ll talk about giving you a better claim.”

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Weighing the Evidence

For a company contemplating a health claim for a product, Johnson recommends careful consideration.

“If you’re thinking about doing a health claim, you need to think about what kind of research you can afford to do to substantiate your claim,” said Johnson. “If it doesn’t have an approved biomarker that can be measured in a reasonable period of time, it’s probably not worth pursuing health claim approval,” he counseled.

As to whether to seek an unqualified or a qualified claim, Johnson offered this recommendation. “What I advise my clients is to go for the highest-level claim you can,” he said. “If FDA is uncomfortable with that, they won’t hesitate to let you know.”

Despite the complexity of getting an FDA green light for even a qualified health claim, such a claim can be a major boon to marketplace success.

Johnson cited the example of the nuts and heart disease claim, which states: “Scientific evidence suggests but does not prove that eating 1.5 oz/day of most nuts as part of a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol may reduce the risk of heart disease.”

That claim went a long way toward changing consumer perceptions of nuts, he maintained. “People were avoiding nuts because they were worried about managing heart [health] or body weight. And the health claim—even a qualified health claim, I think, put nuts in a whole different light. It gave people permission to eat nuts, and—in my mind—legitimately so.

“Since the nut claim was approved, sales of almonds have continued to increase, pistachio sales have increased, and most of it [the marketing message] has been on a health-focused part of the business.”

Thus, despite the hurdles that must be cleared in order to receive approval for a health claim, Johnson is a believer in their merit as marketing tools—provided that the petitioner has appropriate scientific back-up.

“Health claims can be a great way to reach consumers, but it takes sound science and a dedicated strategic approach,” he summarized.

Mary Ellen Kuhn is Managing Editor of Food Technology magazine ([email protected]).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Cracking the European Health Claims Code

Companies seeking to make health claims on products marketed in European Union countries will have their work cut out for them.

That’s the message delivered by attorney Mark Mansour, a partner based in the Washington, D.C., office of the firm Foley & Lardner LLP.

A system of Health Claim Regulation for European Union countries was adopted in December 2006, and European Commission regulators now are in the process of sifting through more than 20,000 health claim petitions. “They’re going to continue going through these for the next year or two, trying to determine what has substantiation and what doesn’t,” Mansour said in the course of a discussion at the Food Technology Presents conference held earlier this year.

The regulatory expert anticipates numerous disputes and lawsuits. They will come “both from consumer activist groups, which oppose nutrition and health claims in principle, and from industry, which believes that the regime unfairly restricts the manufacturer’s ability to communicate with consumers and violates principles of free trade and free movement of goods,” he said.

The European perspective on health claims is different from the U.S. perspective, Mansour explained. “Fundamentally, in the United States, we accept the premise that a health claim, a nutrition claim, a structure-function claim has some merit,” said Mansour. “That is not the philosophy in Europe.

“It has taken many, many years to get European officials to acknowledge that health claims have any merit at all. They have been viewed for many years as … akin to a trick by manufacturers to convince people to buy food that they neither want nor need.”

In Europe, Mansour said, health claims regulation operates with a premise of “restriction, not permission. It’s all based on a premise of, ‘We’ll tell you what you can do. If it’s expressly permitted, it’s fine. And if it’s not expressly permitted, assume it’s prohibited.’”

It’s important to keep in mind that health claims are examined, not just in the context of support for the claim itself, but in terms of the overall healthfulness of the product. In Europe, the mindset is more “good food” vs “bad food” than it is in the U.S., Mansour pointed out.

Evaluating the European regulatory landscape, Mansour offered a few predictions and recommendations.

• Conduct supporting research studies in Europe. “If you want to do this, get European data … American data are going to be viewed as interesting from a scientific perspective, probably credible from an American perspective, but useless as far as validation of a health claim in the European Union,” Mansour said.

• Expect close scrutiny. “I think the more innovative claims are going to face some problems. I think the burden of proof is going to be much, much higher,” Mansour said. Health claims that relate to cognitive function, weight control, and “anything involving children’s health” will be especially “touchy,” Mansour said.

• Proceed with caution. “If you violate the nutrition and health claims provisions, you’re going to have a branding problem because they’re going to start talking about company names rather prominently, and they’re not going to pull any punches,” Mansour counseled. “They’ve made that very clear. You’ll get on a bad list very quickly if your claims don’t pass muster.”