Environmental Testing Goes Viral

FOOD SAFETY AND QUALITY

Some third-party analytical labs are now expanding their test offerings for viruses in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Reaching for tests beyond foodborne enteric viruses (e.g., norovirus and hepatitis A [HAV]), labs are offering environmental monitoring of coronavirus on employee high-frequency-touch-point surfaces. These tests are often used in conjunction with employee monitoring for coronavirus infection. This column addresses COVID-19-related case studies addressed by Marshall and Higby (2020) and Marshall et al. (2020), which considered detection rates, cost effectiveness, employee morale, and validation of cleaning and sanitation standard operating procedures (SOPs). It also summarizes new research with enteric virus surrogates, and methods for decontaminating water in food production that were addressed at SHIFT20.

Controlling COVID-19 in the Workplace

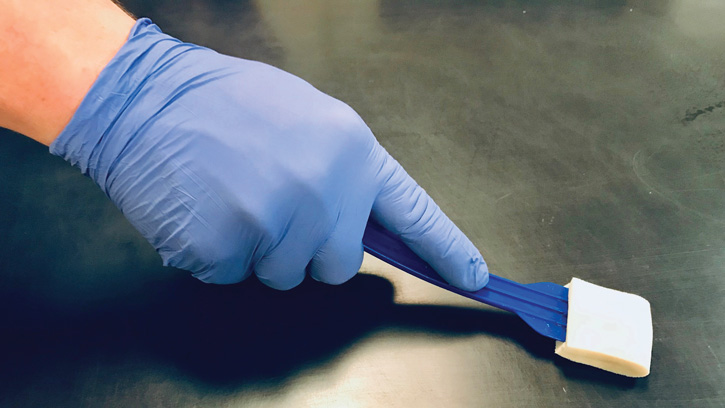

In a Eurofins webinar Douglas Marshall and Richard Higby presented “Screen, monitor, and manage: Real-world examples of how to control COVID-19 risk in the workplace,” reviewing three case studies examining the efficacy and usefulness of environmental monitoring for SARS-CoV-2 (Marshall and Higby 2020). One study was conducted at a meat processing plant after an outbreak, another involved a large global study at five sites in Europe and four in the United States, and the third study was at a long-term care facility. All swabbing was conducted by personnel at each site who were provided a simple instruction sheet with the swab kit. One goal was to test in each facility nonfood contact high-frequency-touch-point surfaces for SARS-CoV-2 contamination. Other goals included correlating surface contamination to COVID-19 confirmed positive employees and performing environmental swabbing after mitigations to evaluate cleaning and sanitization SOPs and effectiveness of physical barriers between employees, personal protective equipment (PPE), and quarantine and social isolation procedures.

In the meat processing plant, a COVID-19 outbreak precipitated a three-week shutdown during which time production lines were re-engineered to provide more physical distance and barriers were erected between workstations. The company also implemented staggered weekly work schedules to further segregate employees; they acquired more PPE and implemented use protocols; and they conducted cleaning and sanitation SOPs. To evaluate these mitigations, 48 high-frequency-touch-point surfaces were swabbed and tested. Also, employees were given an FDA-approved COVID-19 test. Twenty percent of the staff tested positive for COVID-19. These individuals and those who participated in carpools with the positive employees were then excluded from the workforce. Results of subsequent environmental monitoring showed that none of the environmental swab sites were SARS-CoV-2 positive. Thus, the company could now monitor SOP effectiveness and help reassure employees of safety in returning to work. Employee morale improved because management demonstrated concern for their well-being.

In the global study, 5,500 environmental surfaces were tested in nine locations during a two-week period (Marshall et al. 2020). A total of 841 volunteers were tested for COVID-19 infection using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Positive test results ranged from 1.5%–4% depending on the site. The daily environmental monitoring of the high-frequency-touch-point surfaces revealed 44 positive surfaces out of the 5,500 tested, a surface positive rate of 0.8%. The most frequently contaminated surfaces were breakroom chairs, workbenches, door handles, photocopier control panels, toilet handles, elevator buttons, computer mice and keyboards, and file drawer handles. Polymerase chain reaction threshold values (Ct) indicated very low concentrations of RNA on positive surfaces: 34 Ct–38 Ct. Locations with coronavirus-contaminated surfaces were 10 times more likely to have clinically positive employees than locations with no or very few positive surfaces (Marshall et al. 2020).

Long-term, residential care centers present a high risk for residents and staff due to the communal nature of meals and programs. The facilities are hot spots for fatalities due to high concentrations of elderly and immunocompromised residents. In one long-term care facility with 600 staff and 3,000 residents, testing was conducted to evaluate a risk reduction plan when two residents tested positive. The plan included erecting temporary walls as barriers, creating negative pressure in residents’ rooms, confining residents to their rooms, and using a dedicated COVID-19 staff who served only positive residents. Swabbing of environmental surfaces showed positive locations and allowed evaluation of the effectiveness of the plan. Positive swabs were associated only with one COVID-19 positive resident’s wheelchair arm and surfaces associated with that person. The environmental monitoring verifies the care facility’s disinfection practices and other intervention strategies. Communication of these results to employees helped maintain staffing at 100% by improving staff morale.

In summary, environmental monitoring through testing can be used to verify intervention efforts following a workplace COVID-19 outbreak and hasten return of employees to the workplace. Monitoring can also communicate due diligence and a regard for workplace safety to both employees and customers. Further, environmental testing may reduce the need for daily employee testing and thus lower COVID-19 monitoring costs.

‘Food Safety: Going Viral’

In this SHIFT20 session, a panel of experts discussed the global landscape in environmental testing for viruses and risk management. Erin Crowley, chief scientific officer at Q Laboratories and president-elect of AOAC International, indicated that Q Labs has been conducting environmental monitoring for the enteric viruses norovirus and HAV for the past three years. Since the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, she said there has been an upsurge in environ-mental viral testing. She explained that environmental monitoring for viruses, including for SARS-CoV-2 in employee areas and on food contact surfaces, fosters a “culture of safety” in the production setting. Through its SARS-CoV-2 Emergency Response Program, AOAC International is accepting applications for evaluation of multiple test kit models simultaneously to accelerate the certification of environmental monitoring test kits. Crowley shared that in lieu of surrogates AOAC is using in silico analysis to evaluate the kits for inclusivity and exclusivity. More details are available from the organization (AOAC International 2020).

FDA Perspective

“The FDA has nothing to announce with regard to guidance for environmental testing in the workplace and on food contact surfaces,” according to Susan Laine of the FDA Communications and Public Engagement Staff. “It may be possible that a person can get COVID-19 by touching a surface or object that has the virus on it and then touching their mouth, nose, or possibly eyes, but this is not thought to be the main way the virus spreads. The coronavirus is mostly spread from one person to another through respiratory droplets. Unlike foodborne gastrointes-tinal (GI) viruses like norovirus and hepatitis A that often make people ill through contaminated food, SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, is a virus that causes respiratory illness. Foodborne exposure to this virus is not known to be a route of transmission.” The FDA has issued a variety of information for different audiences, including industry guidance, factsheets, and other resources, which are available at the agency’s “Food Safety and the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)” webpage (FDA 2020).

Future Studies

According to Marshall, additional environmental monitoring studies will include air sampling, since COVID-19 is known to be transmitted by particulates and droplets suspended in the air. The data may be used to determine whether respirators are necessary to prevent the spread of disease among employees in high-density, close-contact situations. Preliminary study with wastewater testing protocols showed promise as a semi-quantitative method for monitoring development of an outbreak (Jorgensen et al. 2020). The study found that wastewater testing can detect a community COVID-19 prevalence rate as low as 0.02%–0.1% (i.e., a rate between two virus shedders per 10,000 people and one virus shedder per 1,000). Testing methods such as these can assist epidemiologists in predicting COVID-19 outbreaks in communities.

Research Presented at SHIFT20

Unlike the respiratory virus SARS-Co-V-2, enteric viruses are known to be transmissible via foods since following ingestion they pass through the high acid conditions of the gut to infect the consumer. Norovirus and HAV are the viruses most widely tested by the food industry. Until just recently, norovirus was not culturable in the lab, so nonpathogenic surrogates have been used to determine the efficacy of cleaning and sanitation SOPs and novel decontamination strategies. Use of a viral surrogate also presents lower risk and less expense in terms of necessary equipment and biological safety levels for studying viral inactivation.

Researchers at the University of Tennessee reported growth of Staphylococcus carnosus under specialized growth conditions as a surrogate for HAV (D’Souza and Bowman 2020). They found that decreasing water activity in the growth media by adding 5% sodium chloride or 20% glycerol increased the thermal resistance of S. carnosus. This allowed tweaking the D-values for the microorganism to a range similar to that for HAV. The D-value is the decimal reduction time—the time needed for a one-log reduction of a microorganism of interest at a given temperature (Wikipedia).

Norovirus outbreaks in the United States are most frequently associated with consumption of shellfish and fresh produce. Decontamination of virus-contaminated water associated with both food categories has been suggested as a mitigation strategy (Aboubakr and Goyal 2020). Studies of nonthermal inactivation methods, such as photodynamic treatment (PDT) using LED-blue light and photosensitizers, were conducted on human norovirus surrogates, feline calicivirus, and Tulane virus to reveal the mode of action of these treatments. The researchers indicated that reactive oxygen species were created which destroyed the integrity of viral capsids. They also postulated that viral particles inside the capsid were affected by the oxidation of functional peptides or amino acids. According to the researchers, the photosen-sitizers used, rose Bengal and phloxine-B, are suitable for use as food contact ingredients. Future studies will be conducted to optimize the PDT for use in depuration waters for shellfish and postharvest rinses for produce.

REFERENCES

Aboubakr, H. and S. Goyal. 2020. “Mode of Action of LED-Photodynamic Treatment on Human Norovirus Surrogates in Water.” Presented at SHIFT20, Institute of Food Technologists, July 13–15.

AOAC International. 2020. “AOAC now Accepting Applications for Emergency Response Validation of Novel Coronavirus Test Kits.” Press release, Jul. 24. AOAC International, Rockville, Md.

D’Souza, D. H. and A. Bowman. 2020. “Growth of Staphylococcus carnosus CS 300 with 5% NaCl and 20% Glycerol at 42°C for use as a Hepatitis A Virus Surrogate.” Presented at SHIFT20, Institute of Food Technologists, July 13–15.

FDA. 2020 “Food Safety and the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).” Food and Drug Administration. fda.gov/food/food-safety-during-emergencies/food-safety-and-coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19#5f2139784fbb8.

Jorgensen, A. C. U., J. Gamst, and L. V. H. I. I. H. Knudsen, et al. 2020. “Eurofins COVID-19 Sentinel™ Wastewater Test Provide Early Warning of a Potential COVID-19 Outbreak.” medRxiv medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.07.10.20150573v2. Preprint.

Marshall, D. and R. Higby. 2020. “Screen, Monitor, and Manage: Real-world examples of how to control COVID-19 risk in the workplace.” Webinar. Eurofins.

Marshall D. L., F. Bois, and S. K. S. Jensen, et al. 2020. “Sentinel Coronavirus Environmental Monitoring Can Contribute to Detecting Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Virus Spreaders and can Verify Effectiveness of Workplace COVID-19 Controls.” medRxiv. medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.24.20131185v1. Preprint.

Wikipedia. D-value (Microbiology). en.wikipedia.org/wiki/D-value_(microbiology)#:~:text=In%20microbiology%2C%20in%20the%20context,log)%20of%20relevant%20microorganisms.