Show Them the Money

Science of food salaries have surged, and the employment landscape has changed. IFT’s latest compensation research breaks it down: earnings, expectations, and aspirations.

Article Content

Paydays are getting better. A lot better.

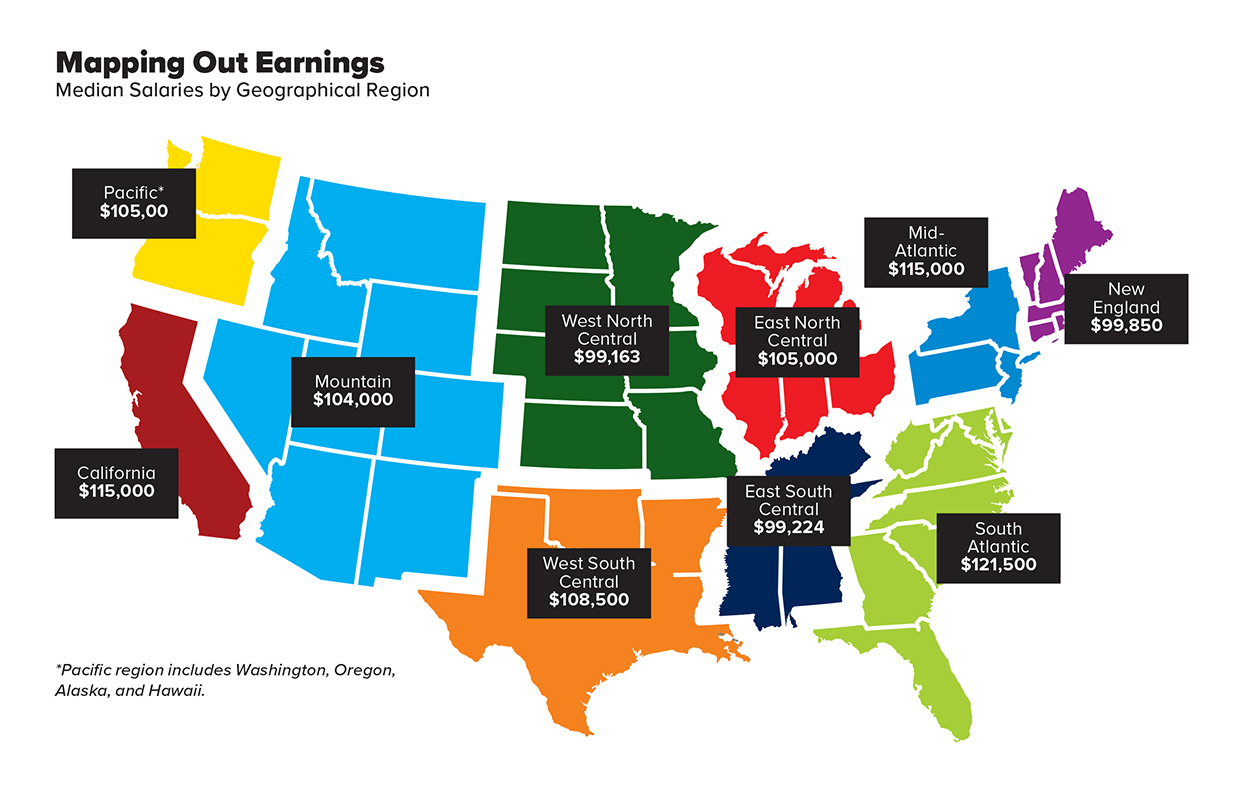

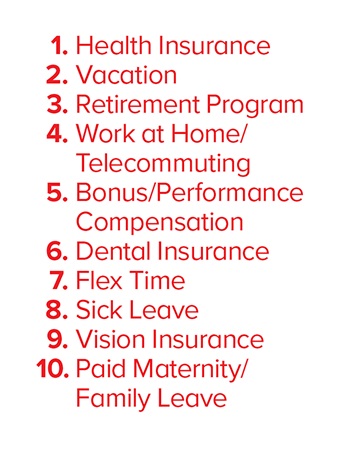

The science of food job market is robust as employers scramble to fill positions that opened up in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced some out of the workplace and prompted others to rethink their career goals, triggering the much-touted “Great Resignation.” In this environment, the median salary for science of food professionals surged to $110,000, up nearly 16% from $95,000 in 2019, the 2022 IFT Employment and Salary Survey found.

“Right now, the candidate has all the power, frankly,” says recruiter Joel Oliver, a partner with food industry executive search firm OSI. “If you don’t wake up to this as an employer, then you just don’t hire or you get an underqualified employee.”

“It’s a candidates’ marketplace—no question about that,” affirms Moira McGrath, president of food science recruitment firm OPUS International. “I think the food industry has stepped up, and they have increased their salaries. They know what they need to pay to get the right candidate.”

Salary growth is strong for “every type of role—whether these are food technologists or plant managers or executive vice presidents of supply chain,” says Oliver.

Fast Tracking It

It’s a very good time to be a young professional in the science of food—particularly if your credentials include a master’s degree and potential for upward mobility.

“The market is booming,” says McGrath, “and everyone wants the same person—whether it’s sensory or R&D or regulatory affairs or process engineering. A master’s of food science with five to seven years’ experience is probably the hottest area right now.

“Everyone wants someone who’s early in their career, who can be promoted as time goes on, [who can be given] more responsibility as the years go by,” McGrath continues. “There are still a lot of baby boomers retiring. The food industry understands they’re losing top talent.”

Talent acquisition currently is a huge challenge, agrees Laurie Hyllberg, vice president at Kinsa Group, a food and beverage executive recruitment firm. “The hardest thing for us to find is that early-career individual—you’ve got maybe two to four years of experience and are ready to take that next step.”

Things are also looking good for entry-level professionals. Starting salaries soared to a median of $77,000, up 33% from the $58,000 median in 2019.

Oliver says this aligns with what he’s seeing in the market. OSI recently placed an associate food technologist who had a master’s degree but no professional experience beyond what she’d gleaned in internships. “Her starting compensation was $75,500, which was above what they wanted to pay,” Oliver notes.

Gap Analyses

The good news about overall salary growth is tarnished by persistent gender- and race-based salary gaps.

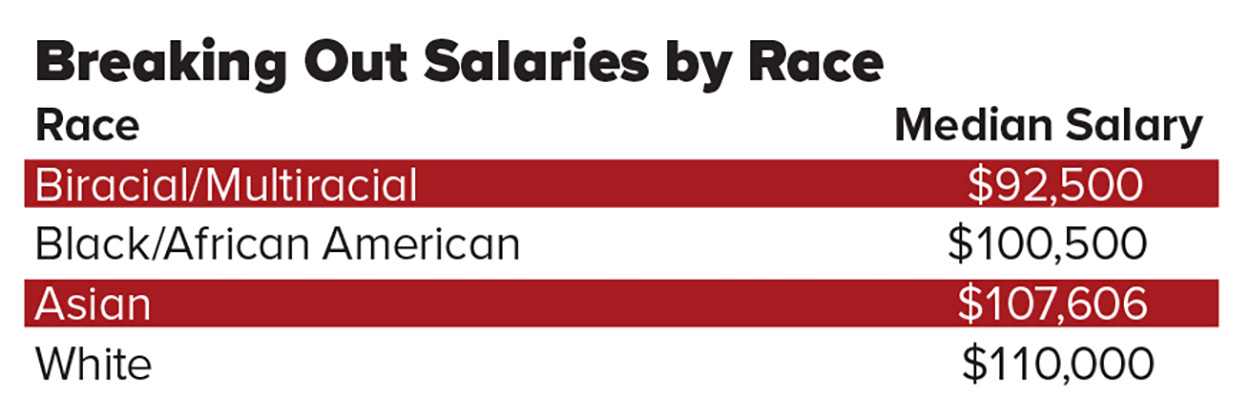

For the first time, this year’s survey compared the median salary of Black science of food professionals with those of white professionals. The median for Black respondents was $100,500, 91% of the $110,000 median for white respondents.

Race-based salary deficits show up across disciplines, says David Turetsky, vice president, consulting, at salary.com, a compensation data and analytics company. “It’s patently obvious that there are differences in pay based on people’s ethnicity or people’s race. And while it’s disappointing, it’s there,” he says. “It’s where our society is right now or where it’s been. And so what are we going to do about it?” (See the interview on page 34 for Turetsky’s take on advancing pay equity.)

Fortunately, many companies are trying to correct race- and gender-based salary inequities, according to Deirdre Macbeth, content director for WorldatWork, an association for compensation and benefits professionals. “With the increased focus on social justice during 2020, it certainly helped provide a heightened priority on fairness and equality in the workplace, including pay equity,” Macbeth says. In 2020, 80% of organizations provided pay equity adjustments, and 86% did so in 2021, according to WorldatWork data.

This year’s IFT survey found that the gender salary gap for science of food professionals is even wider than the racial salary gap. Women’s median salary continued to trail men’s, although the picture has improved since the 2019 survey, where women survey respondents earned just 73.5% of men’s salary.

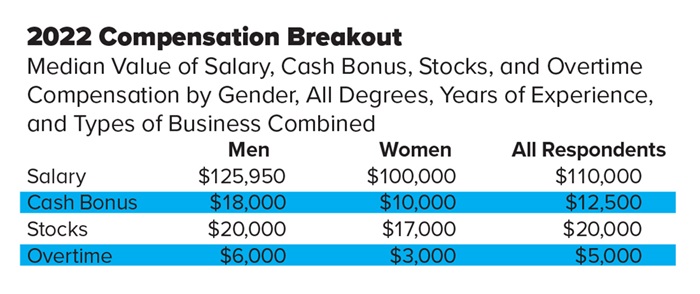

In 2022, the median salary for women science of food professionals was $100,000—79% of the male median of $125,950. Women reported median total cash bonuses of $10,000 in the 2022 survey, 44% lower than the $18,000 median men received. Overtime income, too, was lower for women than for men.

The gender salary gap the IFT survey identified aligns with broader statistics, says Pamela Tolbert, a Cornell University professor of labor relations and organizational behavior who studies salary inequality.

Across the board, the salary situation for women has improved since the 1960s, when they made just about 60% of what men earned, but progress toward eliminating the salary gap has stalled. “It [the gender salary gap] narrowed quite a bit through the 1990s,” says Tolbert, “but it’s really hit a plateau and been stuck at about 80% for the last decade or so.”

There were some bright spots in the survey data for female food professionals. For one thing, women’s salaries are growing at a faster rate than men’s, a trend that surfaced in the 2017 survey. Median salaries for women climbed by 16.3% over the past two years versus growth of 7.6% for the men’s median.

Also noteworthy is the fact that at $55,780, the median salary for female survey respondents aged 19 to 24 exceeded men’s by 5.2%—the only age bracket where women earned more. The gender salary gap was the greatest for those in the 45–54-year age range, where men earned a median salary of $150,000—32.8% more than women in that age range.

“Men and women start out even, but the gap grows the longer they work,” reflects survey respondent Jan Wiley Matsuno, founder of Mindful Food Consulting, who entered the profession in 1979 and has been frustrated by the lack of progress in eliminating the gender wage gap. Her food science career has included product development roles for Del Monte, Safeway, and CCD Innovation.

“Frankly, as a mother of three, I completely understand working part time or taking a less demanding job while caring for children,” says Matsuno. “But the fact that once child-rearing is over, the gap does not reverse, but only gets bigger as women get older, is really frustrating and evidence of the true extent of inequality.” Many factors contribute to this inequality, in Matsuno’s view, including, among others, “lack of support for pregnancy and family leave,” a “lingering ‘good old boy’ network,” and “lack of respect for women in general.”

Experts agree that time away from the workplace has a negative impact on salary trajectories. “Ultimately, you almost always get to the potential conflict between demands of work and demands of family, and women are still primarily the ones who are in charge of organizing family life,” says Tolbert. “Exiting the workforce is indeed costly to women and men, but women are more likely to do this.

“Economists note that technical skills get lost [or] rusty while people take time out of their careers, and employers often take this as a sign of lack of commitment to work,” Tolbert continues, “so if people return to work after time out, they’re less likely to be put in positions with a promotion path.”

Turetsky of salary.com thinks initiatives that reduce the emphasis on salary histories can help eliminate the compensation penalty for women who leave the workforce temporarily by putting the focus on position requirements rather than years of experience and/or past earnings.

One salary survey respondent, a flavor company account manager who is the mother of three sons, believes that it’s important not to paint the gender inequity issue with too broad a brush and to avoid hyperbolic headlines. She feels that her sales-focused career has allowed her to earn a competitive salary and enjoys working in a corporate environment that is supportive of women. “I think it’s a hindrance to people that have traditionally been viewed as marginalized to say that women are treated unfairly in the workplace all the time,” she reflects.

The account manager sees a brighter future for women in the next couple of decades. “We’re in an in-between stage. Only now are women part of the culture where since they were five, they’ve been told they could do anything that they wanted to do.”

She advocates for more family-friendly workplace policies like those that her company already offers new parents of either gender. Companies should have policies in place “so that men are not considered ‘lesser than’ if they choose to take three months off and bond and be a better father,” she reflects.

Both the account manager and Matsuno say that the career experiences they had working with professionals at international companies were sometimes more positive than their experiences with U.S.-based organizations.

“For 13 years early in my career, I worked closely with food scientists in Central America, Europe, and Asia,” says Matsuno. “Interestingly, I found the men there more respectful to me than American men.

“On a positive note,” she adds, “I will say that the working environment has improved a lot during my career. I really enjoy working with young people nowadays. The women are so well educated, and the men are much more civilized and considerate than male coworkers I remember from the 80s and 90s.”

Feeling the Squeeze

The skyrocketing cost of hiring is affecting more than talent acquisition budgets. It’s also having a major impact on the established employee base by causing what is termed “salary compression.”

“The demand for the new hire’s salary, what their ask is, is often higher than what you’re already paying internal employees because the people who move around externally have always gotten higher wage increases,” says Hyllberg.

“Employers are finding that in order to hire someone from outside their organization, they have to pay them equal to or more than existing staff, who most likely have more tenure, higher levels of skills and experience, and so on,” says Kathryn O’Connor, director of compensation services for HR Source, a nonprofit group. “For existing staff, it can be terribly demoralizing to realize that their pay essentially has been diluted or diminished.”

“It’s a challenge,” Hyllberg agrees. “It’s balancing that internal equity—you’ve got to keep your internal top performers engaged and happy with their pay.” Employers should never lose sight of the importance of ensuring that their current talent pool is competitively compensated, Hyllberg counsels. Not only is it the fair thing to do, but it’s far more expensive to recruit and hire a new employee than to retain an existing one, she emphasizes.

“If you’ve got great, engaged employees, try to keep them,” says Hyllberg. “Add some compensation to keep them if they are critical to your success.”

Market Shifts Ahead

In the current climate, salary increases aren’t keeping pace with rampant inflation, even as employers strive to offer competitive compensation. The majority of U.S. employers (73%) are targeting payroll budget increases of 4% or more for the year—and 43% have increased their merit raise budgets by 5% or more, according to a salary.com survey of 1,173 compensation executives.

In periods of high inflation, employers typically give higher-than-normal increases and fund them by increasing the costs of their goods and services—leading to even more inflation, says O’Connor. “For the last 10 years, we have been in this market of 3% pay increases, 3% pay increases, 3% pay increases—and now things have been jolted.”

Wage inflation can’t last forever, however. Giving “increase after increase,” isn’t feasible, says salary.com’s Turetsky. “Margins will dissipate. Companies will go under because they can’t afford to pay people anymore. It’s not sustainable in the long term.”

One change Turetsky expects to see is a move toward making salary information more transparent. “Employers will tell employees exactly how comp is done,” which will help to increase employees’ job satisfaction, he predicts.

Job market trends are cyclical and usually last two to three years, says Loyola University of Chicago professor Dow Scott, who specializes in human resources issues. “Right now, it’s turned on the employers,” he observes.

But given the uncertain economic situation, that could change quickly. “If the economy goes into a big dive, then all of a sudden, jobs will get more scarce,” Scott says.

Food industry recruiters are optimistic about the science of food jobs outlook, which tends to be fairly recession-proof since demand for food is a market constant. Eventually, though, the pendulum will swing, recruiter Oliver acknowledges. “I don’t think it will swing to the other end within the next 12 months. [But] I think it will fall back to the middle.”

How It's Done

How It's Done

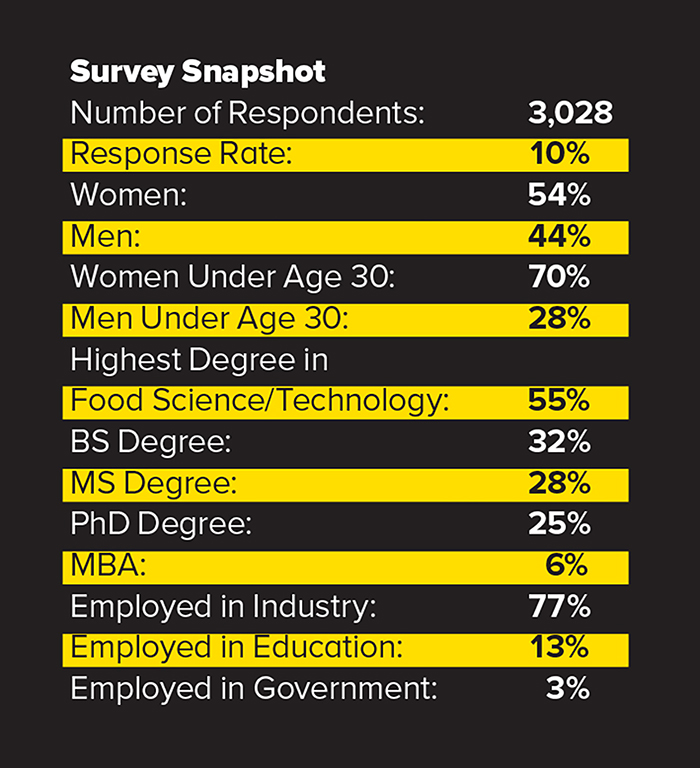

Fielded this past February, the 2022 IFT Employment and Salary Survey drew 3,028 respondents, primarily United States–based IFT members. Some survey participants come from outside the United States, but they were not asked to provide compensation data.

Surveys were distributed by email by a private consulting firm and via links disseminated by individuals and organizations within the food community. Unless otherwise specified, the survey findings reported in this article apply to U.S. respondents. The survey’s margin of error is 2%.

The IFT Employment and Salary Survey was the first in a comprehensive, two-part IFT career research initiative. A second survey, with nearly 3,000 respondents, focused on professional pathways and attitudes about employment.

In addition to more coverage in the November issue of Food Technology, a full report on findings from both surveys will be available free of charge to IFT members this fall and also offered for purchase by non-members.

Bringing Salary Talk Out of the Dark

Bringing Salary Talk Out of the Dark

Most of us don’t want to talk about our salaries. In fact, in a recent survey conducted by YouGov, 11% of respondents said they’d rather run through their office naked than share their salary with coworkers.

David Turetsky says it’s time to lift the veil of salary secrecy. Without salary transparency, we can’t have equity, maintains Turetsky, vice president of consulting for salary.com, a compensation analytics firm. Here’s what he told Food Technology about why the issues of pay transparency and equity are so critically important.

Some states and cities are implementing regulations around pay transparency. What does pay transparency involve?

I used to work for an investment bank. They were angry if they heard an employee was talking about pay. Pay transparency is the opposite of that. Pay transparency is publishing and communicating how pay works so that people understand what they’re paid and why.

What’s the comfort level with pay transparency?

It is a very big departure from where companies are today. Companies are not there. They are in the pay hush, not pay transparency, world. And you know why? Because our culture does not like us talking about pay.

How important is the movement toward pay transparency?

Companies are going to be very successful at pay equity if they’re successful at transparency. And if they’re more secretive about pay, they’re going to be more unsuccessful. That’s just how it is. It’s black and white. You can’t have pay equity without transparency.

How does pay transparency affect the ability to reward for job performance?

Pay transparency makes the pay-for-performance conversation easier for managers because the managers can be more transparent about how things were done. Things now are done in a box. And the box is opaque. So employers can see in, but employees can’t.

If organizations want to be successful, transparency is the way to go. Because pay for performance exists in a vacuum today. No employee knows how their merit increase is created. They don’t know why. They care, but they have no idea.

What’s a simple definition of pay equity?

Let’s go back a little bit and say [that] in the past, pay equity was a check-the-box activity. What we used to do was, we used to say, regardless of who you are, we’re going to pay you similarly. And that didn’t do anything because basically the old rules of when someone comes and interviews with us, we’re going to ask them how much they earned before and we’re going to pay them probably a little bit more than that. And that’s great for us because we may get a bargain out of that person.

And now?

What pay equity tries to do is that it says we’re all going to start people on a level footing. That we’re going to pay them what the job is about. And we’re going to pay them a little bit more if they have experience. We’re going to pay them a little bit less if they don’t.

How does it differ from paying for performance?

With pay for performance, what we did was, we used to pay them for what we could get them in the door for and then give them small increases throughout their career. And if they got promoted, we’d give them a bigger increase. We’d pay them more throughout their career, and we didn’t care about the differences between people [in salaries] because we’d blame it on how they got hired. We’d blame it on the merit increases they got. That’s pay for performance.

Why is a pay equity approach better?

Pay equity basically says we’re paying people similarly. We’re going to pay them fairly for the work that they do. We’re going to hire them in at the same level; as long as they have the same competencies and skills and experience, we’re going to pay the same and not differentiate.

So if a woman has two years less experience because she was pregnant and she gave birth and she stayed home with the kids, we’re not going to ding her because she didn’t have those years’ experience because she’s at the same level in competence as a man who didn’t have to stay home for those two years.

The Power of Benefits

While money matters to most of us, it’s not the only priority for employees. Often benefits are just as important as salary. The pandemic spurred many employees to reevaluate work and how it fits into their lives. For example, half of workers responding to an ADP Research Institute survey said they would trade a pay cut for better work/life balance.

Workers universally want their employment to include the benefits that matter to them, which include both traditional benefits like health insurance and more recently valued benefits like flexible schedules. Sixty-seven percent of job seekers said benefits are more important to them now than before the pandemic, and 54% would consider taking a lower paying job with a better benefits package, according to a survey by Joblist, a resource for job seekers.

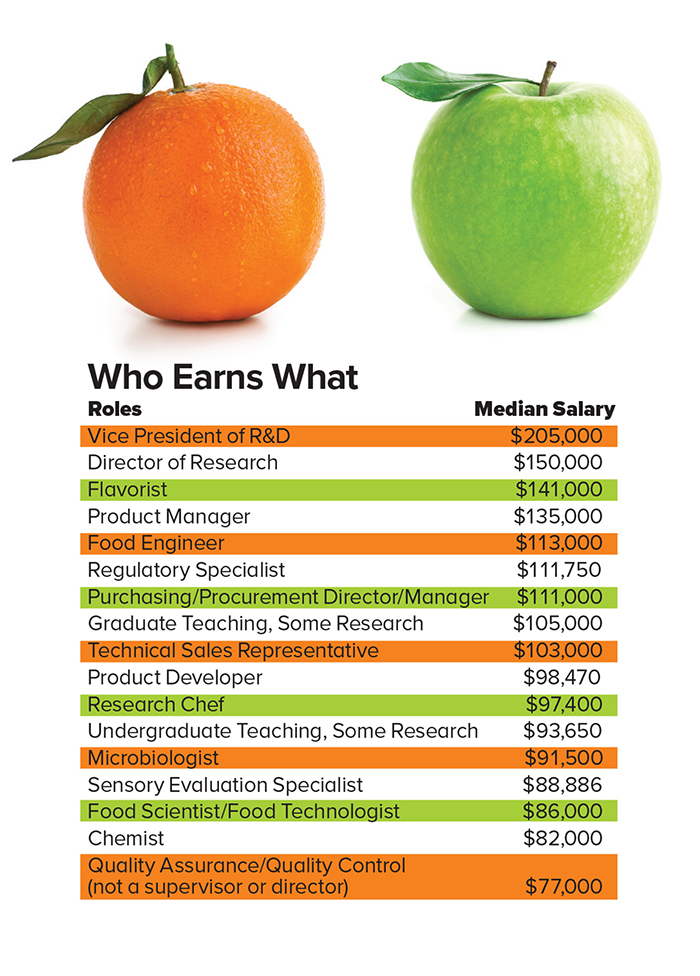

Respondents to the 2022 IFT Employment and Salary Survey were asked to rank the top three benefits in order of importance to them. Not surprisingly, health insurance (offered to 96% of survey respondents) remains the most important benefit to most employees: 70% ranked it first, and 18% ranked it second or third. But respondents also included a number of other benefits in their top three.

Talent in Transition

Thinking about a job change? Odds are good that some of your coworkers are.

One-quarter (25%) of salary survey respondents said they had pursued a job or career change in the past 24 months. Within this group, 23% said they are actively searching and interviewing, and 25% said they weren’t interviewing but were monitoring open positions. Another 32% said they were not actively looking but were open to offers, and 14% had accepted offers.

Now is the time to pay competitively, recruiters emphasize. “Preemptively give them that raise because they’re out there looking more than likely, and if so, they’re going to get an offer elsewhere with more money,” counsels Joel Oliver of executive recruitment firm OSI.

Typically, however, salary isn’t the primary motivator for a job change says recruiter Moira McGrath, president of OPUS International. “It’s never just the money,” she contends. “It’s the whole package. It’s the responsibilities of the job. It’s the opportunities for advancement. It’s relocation, if necessary, or remote [work]. It’s the culture fit as well as the money.”

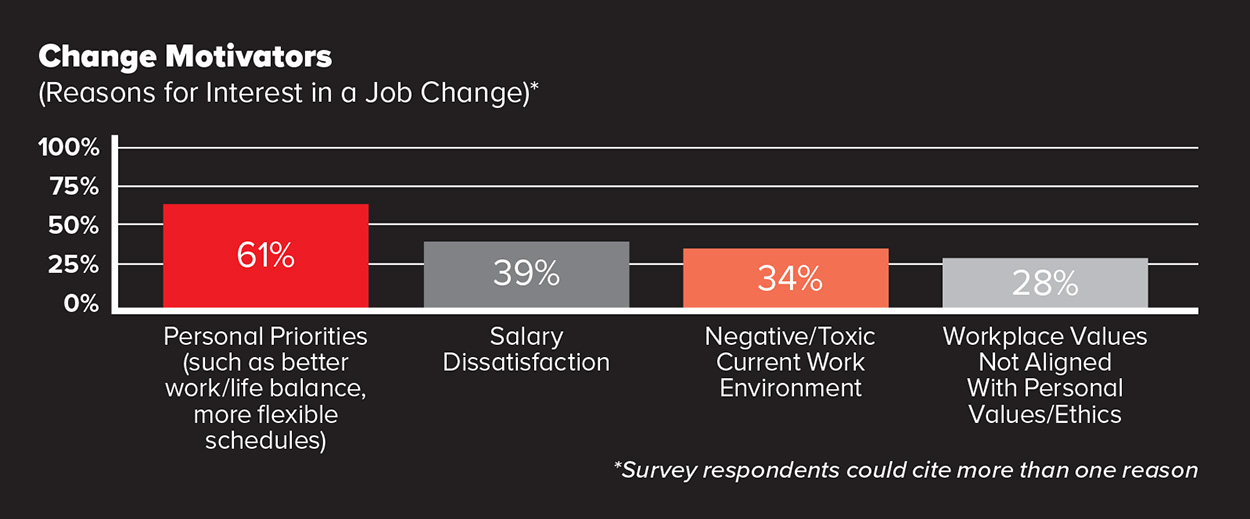

Salary dissatisfaction was a motivator for 39% of those interested in changing jobs, a distant second to personal priorities, such as seeking better work/life balance, cited by 61%.

The New Non-Negotiables

The New Non-Negotiables

Anyone who’s scanned the headlines recently knows that employees’ expectations have changed. For some, the option to work remotely has become a non-negotiable condition of employment and moving for a job is not on the table.

“I just had a job in Boston for a senior director of regulatory affairs,” says Moira McGrath, president of OPUS International, a food science executive search firm. “And I must have talked to 20 outstanding candidates, and 90% of them said, ‘I’m not moving.’

“That was the biggest hurdle—to find someone who was willing to move for the opportunity even though it might have been a step up,” McGrath continues. “It was a step up for everybody that I talked to. Great company. Great benefits. Great salary. But it was the remote piece that everyone was looking for.” Ultimately, she says, the company made a local hire.

It’s not just people in jobs that have traditionally been considered work-from-home positions (a regional sales manager role, for example) who now expect to be able to work remotely, says Laurie Hyllberg, a vice president with recruiting firm Kinsa Group. “Now you’re finding [that with] any administrative job that spends a lot of the day on the computer, their expectation is, ‘I can do this from home’—if not all the time—at least the majority of the time,” she says.

“I’m surprised at the number of QA people in particular who are applying [for a job], and I talk with them and they’re like, ‘Is this job remote? Can it be remote?’” says Joel Oliver, a partner with executive search firm OSI. “I don’t really understand how you could even do this remote. Flex time, sure. There’s some paperwork and stuff like that you could do from home a day or two a week maybe. But I don’t know how you’re going to test your samples from across the country.”

Two-thirds (64%) of the workforce say they would consider looking for a new job if they were required to return to the office full time, according to ADP’s People at Work 2022 survey. And if pushed, employees are prepared to make compromises if it means more flexibility or a hybrid approach to work location: More than half (52%) are willing to accept a pay cut to maintain remote or hybrid work, the survey found.

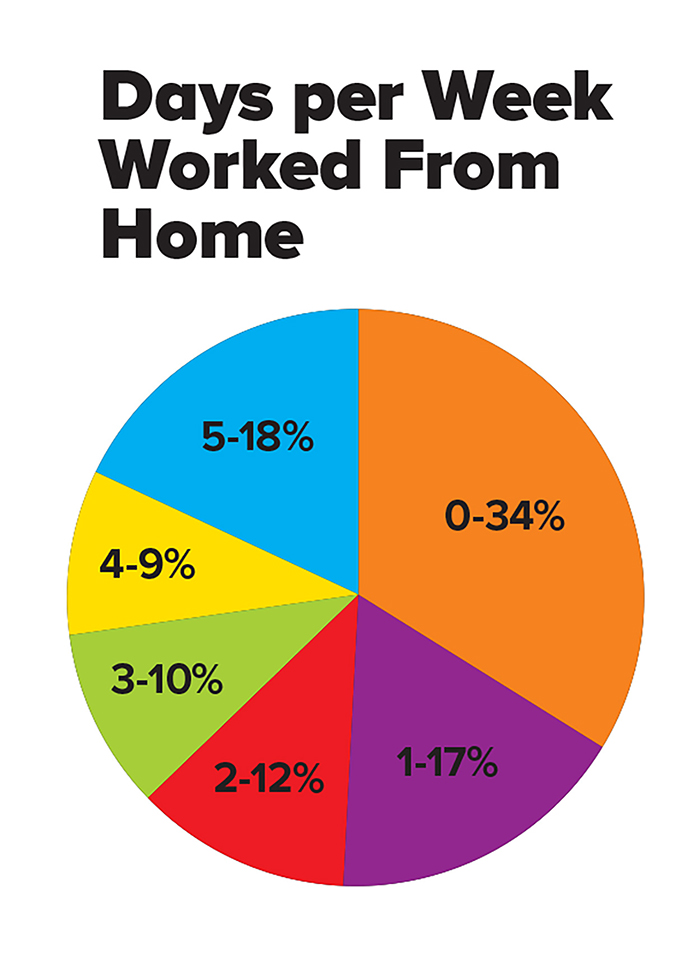

Salary survey respondents work from home an average of 1.9 days per week, with 18% reporting that they were fully remote (five days a week at home) and 34% saying they had no work-at-home days.

Employers have recognized the importance of remote work benefits. In the 2022 IFT survey, 64% of respondents said their employer offered remote/telework options, up from 48% who did so in 2017 and 52% in 2019.

Widespread research suggests that the increase in remote work options isn’t just a temporary response to the pandemic. For example, it’s becoming significantly more common for employers to design jobs to be performed remotely, according to WorldatWork research. Seventy-two percent of respondents in a WorldatWork study designed telework jobs in 2021, up from 63% in 2020.

Employers who are attempting to bring employees back to the office are meeting resistance—and many are giving in, according to the Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes from the Work From Home Research Project created by Stanford and University of Chicago economics professors. For example, among firms that are requiring a five-day return to work, less than half have managed to get employees to adhere to their requirements. In addition, 43% of employees said their employer does not punish workers who come into the office fewer days than required.

Clocking in on Compensation

Clocking in on Compensation

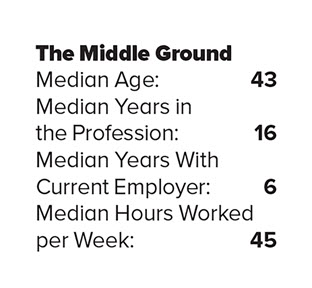

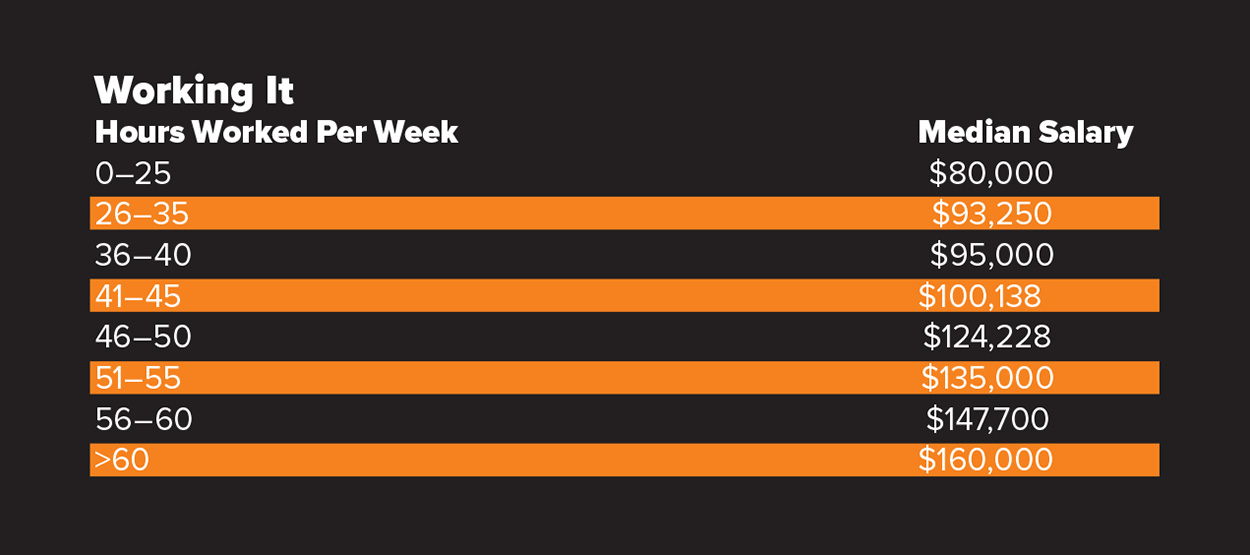

How much you work tends to be related to how much you make. IFT survey respondents who reported working more than 60 hours a week make a median of $160,000 versus half that amount ($80,000) for those who work 25 hours or fewer. In the 2022 survey, respondents reported working a median of 45.1 hours, up just slightly from the median of 44 hours in 2017 and 43 hours in 2019.

Women are said to be less likely than men to subscribe to what Cornell University Professor Pamela Tolbert, an expert on salary inequality, terms “the culture of overwork,” which tends to prevail in disciplines like finance or law, where 60- or 70-hour work weeks are often the norm. That’s traditionally been a contributing factor to the gender-based salary gap, according to Tolbert.

In the IFT survey, however, the median number of hours worked was the same for men and women, and the difference in the percentage of those who reported working in excess of 50 hours a week was minimal: 22% of men and 19% of women.

Are you getting a competitive salary? Is your career on track?

The new 2022 IFT Compensation and Career Path Report is an invaluable resource. IFT's exclusive research benchmarks total compensation, including salary and benefits across the science of food profession. This year’s report expands to include global insights on job satisfaction, career pathways and barriers.