Sanitizing Meat

PROCESSING

Needless to say, people are concerned about the safety of the food they consume. Although most foodborne illness can be attributed to problems in the home, food processors do the best they can to reduce even further any potential for problems.

According to Randy Huffman (phone 703-841-2400), Vice President of Scientific Affairs, American Meat Institute Foundation (AMIF), Arlington, Va., the industry is using intervention strategies on fresh meat carcasses as well as ready-to-eat (RTE) products such as hams, hot dogs, and sliced meats to reduce or eliminate pathogenic microorganisms.

According to Randy Huffman (phone 703-841-2400), Vice President of Scientific Affairs, American Meat Institute Foundation (AMIF), Arlington, Va., the industry is using intervention strategies on fresh meat carcasses as well as ready-to-eat (RTE) products such as hams, hot dogs, and sliced meats to reduce or eliminate pathogenic microorganisms.

With regard to fresh meat carcasses, some of more well-established interventions being used are steam pasteurization and steam vacuum. In a steam pasteurization system, the carcass is exposed to a blanket of steam as it passes through a steam cabinet. In a steam vacuum system, the operator uses a handheld device to spray steam directly onto areas of the carcass where contamination is suspected. Both methods are widely used in the industry.

Also widely used are sprays and organic acid washes, such as lactic and acetic acids. A hot water wash of the carcass before chilling and fabrication has also been shown to be as effective as some of the more costly interventions, Huffman said. Some work is going on looking at interventions for trimmings during fabrication of products destined for further processing, such as ground beef and other products. Various approaches, such as steam treatment and additives, are being considered.

Irradiation of meat has also been approved and is being used by several companies (see below), while others have been waiting for approval of some packaging materials, he added. The Food and Drug Administration on February 16, 2001, expanded use of x-ray and e-beam irradiation (in addition to the already-approved use of gamma irradiation) for the treatment of prepackaged foods. The amended regulation allows all packaging materials that had previously been permitted for use during gamma irradiation to now be used during e-beam and x-ray irradiation.

It is becoming more and more obvious that the key to success is to have multiple interventions in place, Huffman said. In line with this, AMIF is funding a number of projects related to reducing or eliminating contamination by Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Listeria monocytogenes. One probiotics study—a competitive exclusion approach targeted at E. coli O157:H7—will start this spring. Other researchers are looking at on-farm technology, studying the possibility of using bacteriophage targeted at E. coli O157:H7—a project very much in the experimental stage. Another project is looking at the distribution of virulent and avirulent strains of E. coli O157:H7; although not focused on intervention, the study can help us understand ecology better and develop better control strategies, Huffman said.

With regard to RTE products, FDA announced on January 5, 2000, that the Food Irradiation Coalition had petitioned for approval of irradiation of a variety of foods, including RTE meat and poultry products. AMI and other trade organizations are part of the coalition, which is hoping for approval soon.

There is a lot activity regarding strategies to control L. monocytogenes, the biggest challenge, Huffman said. The majority of meat products are thermally processed to destroy Listeria. The result is virtually a pasteurized product, he said, but many products get exposed to the environment between cooking and packaging. So all strategies are focused on eliminating post-cooking contamination and preventing growth of Listeria in the finished product. Various ingredients help control the growth of Listeria, including sodium lactate and sodium diacetate. About a year ago, the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service announced an increase in the amounts of these ingredients that can be used, giving processors more flexibility.

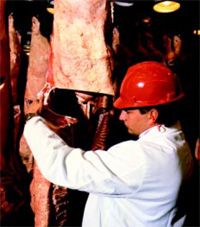

Listeria is capable of growth under refrigeration and grows well in niches in the processing environment, which is wet and Photo courtesy of IBP, Inc. cool. The microorganism has salt tolerance and many unique features that make it difficult to control. There are quite a few projects, including studies on optimal irradiation doses, and use of natural compounds such as extracts of rosemary and thyme and other natural ingredients.

Among the studies being funded by AMIF are a study at the University of Wisconsin on efficacy of cleaners and sanitizers on Listeria biofilms, including assessment of various surface coatings that will inhibit attachment; a study at Iowa State University to determine the ability of Listeria to attach to RTE meats, the optimal radiation dose required to eliminate Listeria using an electron-beam source, and the survival and growth of Listeria in RTE meats after irradiation processing; a study at the University of Georgia to prevent contamination of Listeria in foods by eliminating/reducing its occurrence in food processing through use of competitive exclusion microorganisms; and a study at Kansas State University to optimize the application parameters (spray, temperature, pressure, and contact time) of cetyl pyridinium chloride for control of Listeria in RTE meats.

In another project funded by AMIF that is just beginning, Jimmy T. Keeton (phone 979-845-3936), Professor of Animal Science at Texas A&M University, College Station, will study decontamination of RTE products by incorporating new types of antimicrobial agents into the products or applying them as rinses after they are cooked but just prior to packaging. He will look at the effect on L. monocytogenes of three agents: (1) Safe2O™ HOH (“safe water”) a proprietary product from Mionix Corp., Naperville, Ill., consisting of sulfuric acid and calcium hydroxide in combination with lactic or propionic acid, all of which are considered generally recognized as safe (GRAS), used as an ingredient and as a rinse; (2) a 3.3% potassium lactate dip; and (3) a 3.4% lactic acid dip.

Keeton said that in production of ground beef, the main concern is decontamination of the product before it gets to the grinder, so decontaminating the carcass as much as possible would be a great benefit. The biggest challenge is just keeping the product clean and safe, keeping contamination off of it. There could be other organisms that arise over time, he said, but Listeria is the one they are most concerned with now because it can grow at refrigeration temperatures and is a serious pathogen.

According to Daniel L. Engeljohn (phone 202-720-5627), FSIS’s Director of Regulation Development and Analysis, a variety of antimicrobial agents are being used on fresh meat carcasses as a means of reducing or eliminating E. coli O157:H7. The industry is also looking into treating raw beef trimmings with antimicrobial treatments.

On October 20, 1999, FSIS published a final rule updating its sanitation requirements for official meat and poultry establishments. It converted many of its highly prescriptive sanitation requirements to performance standards and consolidated sanitary regulations applicable to both meat and poultry establishments. The rule took effect on January 25, 2000. Engeljohn emphasized that the sanitation performance standards are effective in having an establishment maintain a sanitary environment. Establishments can supplement them with irradiation and antimicrobials, but not in lieu of sanitation. They must still meet sanitation procedures and controls.

On January 9, 2001, FSIS issued regulations to limit the amount of water retained by raw, single-ingredient meat and poultry products as a result of post-evisceration processing, such as carcass washing and chilling. Raw livestock and poultry carcasses and parts will not be permitted to retain water resulting from post-evisceration processing unless any water retained is an inevitable consequence of the process used to meet food safety requirements. The rule becomes effective on January 9, 2002, and also requires labeling of the maximum percentage of retained water unless the retained water is an unavoidable consequence of meeting food safety requirements.

Industry is looking at ways to significantly reduce the level of microorganisms on raw meat to be used for ground beef, Engeljohn said. The agency intends to begin implementing its E. coli policy, forcing industry to no longer concentrate only on finished raw ground beef products but to start focusing on trimmings and carcasses.

Engeljohn added that he is hoping that industry will incorporate treatments into their HACCP programs. FSIS will start concentrating on the content of those programs. Until now, the agency was conducting basic reviews to determine that companies had written HACCP plans and records. Now the agency will look at those HACCP plans and how the hazards are being controlled.

FSIS doesn’t have research authority, but it does have in place a program that allows industry to do experimental research in federally inspected facilities. If industry wants to use a new technology or inspection process, it can contact FSIS for approval, as long as it doesn’t affect worker safety or product safety, Engeljohn said.

He added that the agency is doing everything it can to ensure that industry has the flexibility to develop new technologies and conduct experiments in plants to enhance the safety of meat, poultry, and egg products. If a company thinks it can do something but thinks it doesn’t have the regulatory flexibility to do it, the company should contact FSIS. The agency is willing to work with industry on something new and innovative if it enhances food safety, he said.

On November 27, 2000, FDA issued a final regulation allowing use of a mixture of peroxyacetic acid, octanoic acid, acetic acid, hydrogen peroxide, peroxyoctanoic acid, and 1-hydroxyethylidene-1,1-diphosphonic acid as an antimicrobial agent on red meat carcasses, in response to a petition by Ecolab, Inc., St. Paul, Minn. The additive mixture can be used at a maximum concentration of 220 ppm as peroxyacetic acid, and the maximum concentration of hydrogen peroxide allowed is 75 ppm.

Ecolab immediately began marketing the mixture as Inspexx™ 200. The product can be applied at concentration levels 100 times lower than other treatments currently available, according to Richard Higby, Ecolab’s Senior Marketing Manager, Meat & Poultry (phone 651-293-2024). Very few antimicrobial compounds for meat are actually documented as being effective oxidants and biocides, he said. Acetic acid (as well as lactic acid) is used to create an acidic environment in which bacteria don’t survive well, in the hope that they won’t survive. Only by making it into an oxidant such as peroxyacetic acid can you get a true bactericidal effect. Inspexx 200 is made by a patented process involving mixing hydrogen peroxide and acetic acid together to generate an equilibrium mixture of all three.

It is effective in reducing microbial contamination on red meat surfaces, such as E. coli O157:H7, L. monocytogenes, and Salmonella typhimurium. It’s less corrosive and has less impact on the plant environment, and no activation or generation equipment is required. It is also compatible with waste treatment systems, since it contains less than 4 ppm of phosphorus and no chlorine. It rapidly breaks down after use into water, oxygen, octanoic acid, and acetic acid. It is considered an active intervention strategy in USDA’s HACCP program.

Ecolab approaches meat plant sanitation in several ways: through use of food-contact-surface sanitizing agents, meat-surface sanitizing agents, and irradiation, the latter through a partnership with IBA, headquartered in Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium. Ecolab is the exclusive marketing agent for IBA’s e-beam and x-ray food irradiation technology.

Higby said that one of the major challenges is innovating new products in view of the regulatory burden to demonstrate safety and efficacy. Any new ingredient has to go through FDA’s food additive petition process, and to be implemented in the plant it has to be authorized by FSIS. It adds 18 mos to 3 years to the time frame for introducing something brand new, he said.

Another challenge is creating the original active ingredient that will be effective. There are a limited number of products that can be used from the chemical perspective without adversely affecting the appearance and flavor of the food. Ecolab uses peroxyacetic acid chemistry, although other chemistries are available. Nevertheless, new and truly innovative products are relatively few, he said. One of the newest red meat antimicrobials is lactoferrin, but it is fairly expensive, Higby said. The challenge is to reduce the cost of the material application to a reasonable level. Trisodium phosphate is being used for poultry and being considered for use on red meat, but there is a growing need to have organic products now and phosphates aren’t organic. Organic acids such as acetic and lactic acids have to be used at fairly high weight percentages (approved up to 2.5% sprayed on), but they are corrosive to the plant environment and fairly expensive compared to steam pasteurization.

Steam pasteurization is a largely mechanical thermal process. The surface has to be dry, so there can be problems if the steam is not hot enough or the meat surface is too cold or wet. Ultraviolet light has been tried, too, but irradiation is the only process that will assure very effective antimicrobial action, he said. It is being used on packaged products. Probably the most effective is x-ray technology, because of the stigma attached to gamma irradiation and the lack of depth of penetration by electron beams.

On December 23, 1999, FSIS approved irradiation of refrigerated or frozen raw meat and meat products to significantly reduce or eliminate E. coli O157:H7 and other hazardous microorganisms. Irradiated products must still meet all other food safety requirements, including sanitation and pathogen reduction standards. Three types of irradiation have been approved: gamma, electron beam, and x-ray.

In May 2000, Huisken Meats, Chandler, Minn., became the first company to market irradiated beef in the United States, when it introduced its irradiated frozen beef patties under the Huisken™ and Taste Club™ brands in Minnesota. The products, which are e-beam-irradiated by SureBeam Corp., San Diego, Calif., are now being marketed in 18 states. Other meat products e-beam-irradiated by SureBeam are now being marketed all across the U.S. by IBP, Inc., Dakota City, Neb., Omaha Steaks, Omaha, Neb., Excel Corp., Wichita, Kans., Emmpak Foods, Inc., Milwaukee, Wis., and Schwan’s, Marshall, Minn.

In June 2000, Colorado Boxed Beef, Auburndale, Fla., began marketing irradiated fresh ground beef and frozen beef patties under the New Generation brand in several retail markets in Florida. The products are gamma-irradiated by Food Technology Service, Inc., Mulberry, Fla.

IBA is currently building a commercial irradiation facility in Bridgeport, N.J. It is expected to be completed this month but will not be open for commercial use until May or June. It will have both e-beam and x-ray systems, but will use only x-ray for food. According to Chip Colonna (phone 901-681-9006), Vice President, Perishable Foods at IBA’s Food Safety Division, Memphis, Tenn., the Bridgeport facility will be equipped with IBA’s 135-kW Rhodotron TT-300 electron accelerator.

He added that Ecolab/IBA has other irradiation facilities in operation or under construction. Recently, IBA announced the installation of a dedicated x-ray system at the Carthage, Mo., facility of Americold, the largest provider of cold storage in the U.S. Expected to be operational by June, it will be dedicated to irradiation of packaged foods, everything from meat and poultry to RTE products. IBA also has received a USDA grant of inspection for its gamma-irradiation facility in the Chicago area, and it has an x-ray test facility in Long Island, N.Y., where it has been testing meat and poultry products. In addition, several major RTE processors have tested product in anticipation of the approval of the RTE petition.

On August 19, 1999, FDA announced that FSIS had submitted a petition asking FDA to approve irradiation of unrefrigerated, uncooked meat, meat by-products, and certain other meat food products to reduce levels of foodborne pathogens and extend product shelf life; this petition is pending. On January 5, 2000, FDA announced that the Food Irradiation Coalition had filed a petition asking FDA to approve use of irradiation on a variety of foods, including preprocessed (RTE) meat and poultry products but not raw meat products. Issuance of a final rule on irradiation of RTE meats is expected soon.

Other antimicrobial additives are being used or tested. Cetyl pyridinium chloride has been approved as GRAS by FDA for use as a disinfectant for the exterior of packaging bags in which meat and poultry products such as deli meats are cooked. The substance is marketed as Cecure™ by Safe Foods Corp., North Little Rock, Ark. According to Amy Waldroup (phone 501-758-8500), Director of Research & Development, after the meats are cooked in the bag, the antimicrobial is sprayed onto the outside of the bag as it enters a clean room so the bag doesn’t serve as a vector for cross-contamination. The cook-in bag is then stripped from the meat product. The company submitted a draft food additive petition to FDA last fall for use of the antimicrobial as a treatment for raw meat carcasses, received FDA’s comments, and plans to resubmit the petition shortly. The compound is effective against Listeria, Salmonella, E. coli, and Campylobacter.

Acidified sodium chlorite, a combination of citric acid and sodium chlorite in an aqueous solution, is being marketed by Alcide Corp., Redmond, Wash., under the tradename Sanova®. It was approved for pathogen control on red meat carcasses and products on January 12, 2000. It can be applied as either a spray or dip. It has been approved as a food additive for use on meat, poultry, seafood, and fruits and vegetables, as well as on food-contact surfaces. It is currently being reviewed for use in RTE products, including hot dogs and other sausages, and as a post-chill application for poultry. It can control E. coli O157:H7, Campylobacter, Listeria, Salmonella, and other microbial contaminants on meat surfaces.

According to Cayce Warf (phone 425-882-2555), Alcide’s Director of Research, Sanova received FDA approval as a carcass rinse in 1998. The company ran a successful pilot test using the antimicrobial as a carcass rinse prior to chilling at a meat slaughtering plant in northern Illinois last summer and is putting in a complete installation there. The company also ran a successful pilot test on beef trim to be ground to make hamburgers at a meat processing company in Milwaukee, Wis., and is now putting in a complete installation there. On February 13, 2001, FSIS amended its approval on post-chill red meat parts and trim and primal cuts to allow use of the antimicrobial without the for supplemental labeling of the treated product.

Activated lactoferrin is currently being tested as an antimicrobial spray for beef carcasses by Farmland National Beef Packing Co., Kansas City, Kans. According to its developer, A.S. Naidu (phone 909-869-3788), Professor at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, the GRAS substance can be applied as an electrostatic spray in microgram quantities, making it much less expensive than previous studies have indicated. The aqueous solution of lactoferrin is made by a patented immobilization process that keeps the substance biologically active. Activated lactoferrin has been shown to be effective against E. coli O157:H7, other serotypes of enterotoxigenic, enteropathogenic E. coli, Salmonella, Campylobacter, and a variety of other foodborne pathogens and food spoilage organisms, including radiation-resistant species.

PRODUCTS & LITERATURE

E-Beam Irradiation is offered to reduce microbial content of bulk ingredients and packaged products. The process applies a controlled high-energy electron beam that requires no chemicals, leaves no residue, and does not alter appearance, taste, or chemical makeup of the product or package. For more information, contact E-Beam Services, Inc., 118 Melrich Rd., Cranbury, NJ 08512 (phone 877-413-2326) —or circle 310.

Can Inspection System, the TapTone 500, combines a proximity sensor to measure lid curvature and an x-ray fill level sensor to detect and automatically reject cans with deflective lids, flat lids, missing lids, cocked lids, seam defects, knockdown flanges, dents, low fill, overfill, or low vacuum. The high-speed, noncontact system allows users to set their own rejection parameters, provides on-screen diagnostics for troubleshooting, and features a menu-driven keypad. For more information, contact TapTone Package Inspection Div., Benthos, Inc., 49 Edgerton Dr., North Falmouth, MA 02556-2826 (phone 800-423-4044 or 508-563-5920, fax 508-564-9945, www.taptone.com) —or circle 311.

Decanter Centrifuge with clean-in-place (CIP) capabilities features an over-hung design of the process area. This keeps the drive section and all bearings and seals physically separated from the process, guaranteeing no cross-contamination. The new centrifuge easily separates liquids and solids down to 2 microns of materials with different specific gravities. The all-stainless-steel construction readily lends itself to clean-room applications and facilitates a complete washdown. For more information, contact TEMA Systems, Inc., Centrifuge Div., 7806 Redsky Dr., Cincinnati, OH 45249 (phone 513-489-7811, fax 513-489-4817, www.tema.net) —or circle 312.

Daily NEWS

For the latest food industry news, analysis & trends, check out . . .

www.ift.org/dailynews/index.html

by NEIL H. MERMELSTEIN

Senior Editor