Packaging Innovation as a Marketing Tool

PACKAGING

More than 15,000 new food products are introduced annually in the United States, all of which require new packaging, even if the contents are just line extensions. In addition, an uncounted number of food products, perhaps about 1,000, are repackaged annually, each requiring some attention.

Obviously, not every new package represents an innovation; in fact, most are serviceable repeats with edited labels. On the other hand, a substantial number are intended to perform some technical or marketing function beyond their immediate antecedents, and some are aimed at really disturbing the conventional wisdom of food packaging, thus generating a new generation of purchasers and users.

As I thread my way through the maze of food packages developed, engineered, crafted, and designed to protect, preserve, communicate, heat, cool, and otherwise dazzle consumers, I am increasingly struck by the quantity—and occasionally, quality—of the offerings. As many times as I have been involved in innovating by creating, piggybacking, or cloning (without directly infringing) on behalf of my own or client organizations, I wonder how others approach the challenge of competing in the fiercely competitive world of retail food, armed with packaging as one marketing tool.

Packaging and Technology Integrated Solutions (www.pti-solutions.com) pondered this question and undertook to answer it with a deeply drilled study and analysis. PTIS conducted in-depth research of more than 100 significant consumer packaged goods companies and probing analyses of the raw data. Some of the results of the proprietary study, "Packaging’s Seat at the Table," available from Packaging Strategies (www.packstrat.com), are discussed below.

Education in Packaging as a Marketing Tool

Most marketing texts barely touch on packaging as a marketing tool, and very few packaging texts devote more than passing paragraphs to the increasingly intimate relationship of packaging and marketing. But consumer goods companies are expanding their employment of persons with the title of Packaging Vice President and compelling marketing, brand, and product managers to apply packaging as one of their key weapons in the ever-increasingly competitive marketplace. Packaging is today and more so tomorrow an indispensable vehicle to holistically deliver food to consumers.

And the delivery mechanisms within food companies and their downstream channels, the value chain, are increasingly more complex, embracing not just those chosen for their marketing skills but everyone in the chain, including the food scientist/technologists and their packaging partners.

The New Packaging Models

The new (corporate) packaging development models (not yet universally applied) require all participants to think about food packaging differently to provide better insights and thus deliverables.

• Horizontal Value Chain Model. This model consists of the demand plus the supply chain, and profit and cost centers. Packaging is the key enabler and differentiator for products across categories but until recently has not been fully appreciated. Food packaging functions throughout the value chain, including the raw material suppliers, converters and equipment suppliers, food processors and packagers, retail channels, consumers, and final disposition of the expended package.

Focusing on the chain links with which food and food packaging scientists and technologists are usually immersed, we can enumerate food processor/packagers, distribution channels, and disposal. Within food processor/packager/marketer organizations, marketing is changing because among consumers, convenience is huge, time is critical, and food is fun, safe, nutritious, and replete with quality. Food companies expect more from their converters, which, unfortunately unlike in the past, today have fewer resources to offer their customers. Food companies want to start small; they want to balance innovation with productivity; they are squeezed by their distribution channels and costs; they are trying to do more with less. Packaging development is tight, occupied mostly with day-to-day troubleshooting and productivity issues. Nevertheless, marketers want shelf and kitchen impact derived from a renewed focus on innovation.

Channel members and, in particular the retailers, have changed radically and continue to flow down the rivers of change. Nearly half the food volume and almost all the future food growth rests in the foodservice channel. For good or otherwise, the Wal-Mart distribution model has forever altered grocery delivery on this planet. All retail distribution is characterized on the one hand by consolidation and on the other by an ever-moving tide of splintering into ethnic, specialty, dollar, limited assortment, etc., to a record nearly 200,000 outlets, blurred boundaries on categories, not counting vending, mail order, and e-mail order. All want higher-value products fronted by their distinguishing package. All have electronic data that inform about movement per shelf millimeter and per facing, mimicking consumer behavior.

And packaging is now commanded to be the renewed future driver to make all problems right. The PTIS study indicated that 80% of food companies regarded packaging as "very important," but that only 20% of them involved packaging in preconcept work on new product development. When asked about the point of involvement of food packaging professionals, 37% claimed that packaging is involved "early" in the product development process and collaborates closely with marketing, with many resources available for innovation. A majority of those surveyed agreed that the packaging should play a larger role early in the development process, in a more integrated fashion. Yesterday and now, marketing controls the budget — and mostly does not understand the technical and consumer benefits delivered by packaging. Today’s crucial take-away is that suppliers and their customers must be aligned—or is it that marketing and technology must function in concert?

In the traditional packaging value chain, primary raw material suppliers fed (and received feedback from) converters, who, in turn, supplied food processors/packagers, who also sometimes offered feedback to their prized converters. Food processors/packagers sent their packaged foods through distribution channels and eventually arrived at retail outlets for consumers to acquire. Within the food processors/packagers were (and mostly still are) such functionalities as purchasing, operations, logistics, product development, marketing, sales, engineering, and, on occasion, packaging. In this soon-to-be obsolete model, there was little or no linkage, value, or innovation, but cost was omnipresent.

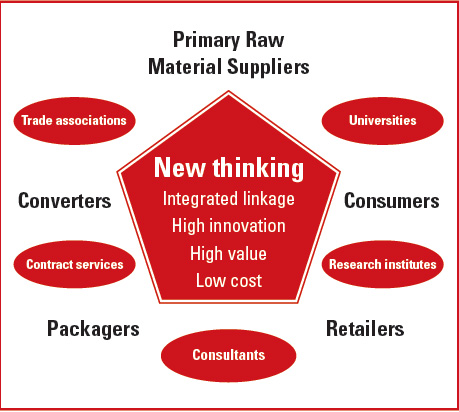

• Integrated Value Chain Model. In today’s and tomorrow’s integrated value chain model, every member overtly participates, linking innovation, value, and, above all, thinking with active consumer input (Figure 1).

• Integrated Value Chain Model. In today’s and tomorrow’s integrated value chain model, every member overtly participates, linking innovation, value, and, above all, thinking with active consumer input (Figure 1).

Regardless of marketing, scientist, engineer, or consumer perceptions, food products are the integral of contained product plus package plus brand equity plus adjunct services: the product is the package and its delivery system. Its value is measured by its benefit:cost ratio vs any substitute or competitor. Packaging strengthens core brands, offers new brands, and enhances the value equation. For example, packaging is widely credited with being the key driver for such "product" successes as extended-shelf-life flavored milk beverages; fresh-cut vegetables; microwave popcorn; moist pasta; microwave entrees and soups; shredded cheese; bottled water; and many more.

Packaging Innovation

Innovation in packaging begins with its definition: development and commercialization of a product that results in a successful launch that meets or exceeds the target or even alters the way we function (e.g., in-car eating), or development that disrupts the conventional wisdom but might not, for a variety of reasons, meet forecasts. Company strategy should dictate the package innovation charter: follow the leader (e.g., private label, at nearly a quarter of foods and growing in importance and quality); incremental—short term; search and reapply—utilize best practices within and external to the category; and discontinuous—totally changing the game while building business and margin (e.g., condiment squeeze bottles with inverted labeling or lunch kits or the new microwave pizza). Not so clear is the risk–reward equation: continuous small steps such as cost reduction or line extension are low in risk and low in return. The bold moves have the potential to change the world but carry with them high risk (e.g., self-heating coffee cans).

One answer is to have a clear objective within the company strategy and to invest in the early conceptual stages where failure is not nearly as costly as after scale up. A food packaging road map for these exercises is a comprehensive dynamic portrayal of the future, with short-, intermediate-, and long-term objectives.

In the near future, look for several "easy" innovations that may resemble the competitor’s. For the distant future, look to the stars, such as biomass polymers as they might influence chilled distribution and consumer disposal. In between is where the gold can be mined, requiring daring to test the technologies and the market (e.g., ultra-high-pressure-processed guacamole with its attendant stresses on the package structures that had to be solved).

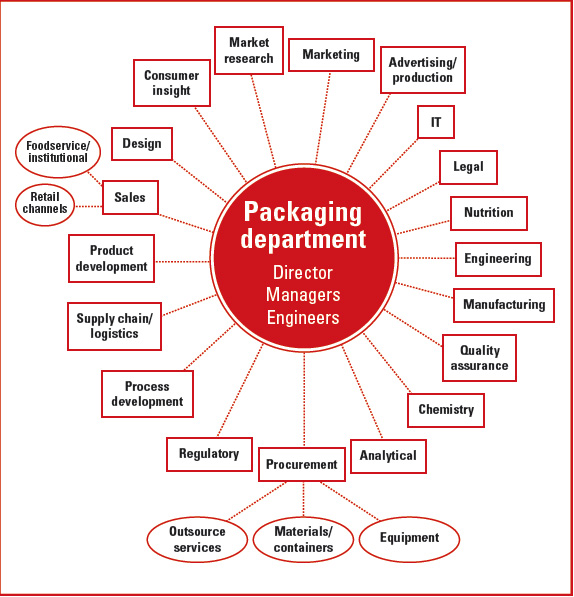

To perform the packaging innovation, packaging professionals have many constituencies to which they report and/or are responsible (Figure 2). They may be broadly classified into four areas—innovation, marketing and project support, cost savings and/or productivity, and firefighting—plus the underlying foundation of skills and resources capable of performing the tasks.

To perform the packaging innovation, packaging professionals have many constituencies to which they report and/or are responsible (Figure 2). They may be broadly classified into four areas—innovation, marketing and project support, cost savings and/or productivity, and firefighting—plus the underlying foundation of skills and resources capable of performing the tasks.

Always within these matrices is the need to cooperate closely with suppliers and distribution, as well as with the internal organization, which cannot be siloed into departments to await this week’s results before moving forward—with the entire process driven by professionals with vision and the courage to step where no one else has. Young folks cannot imagine a world without easy-open beverage cans or microwave popcorn. Old pros—even those who before color television microwave-popped their corn in kraft paper bags—cannot fathom how anyone could possibly have constructed an expandable fat- and moisture-resistant, multiplex paper/polyester bag with hidden integral microwave susceptors and steam dissipation.

When marketing packaging innovation within a food organization (internal marketing is a key element of any marketing plan), the offering must align with the business-unit strategies. With consumer insights in hand, the professional can link consumer needs to the business and then search for the technology that best fits the solution. The "sweet spot" of so many product development texts is the logical convergence of business strategy, consumer insight, and technology. Having hit the target, it is now the organization’s responsibility to possess the chutzpah to stay the course.

Consumers want safety, flavor, convenience, variety, nutrition, fun, and perceived value. Meet these criteria with the product/package integer and the package becomes relevant to the target consumer.

by Aaron L. Brody,

Contributing Editor ,

President and CEO,

Packaging/Brody, Inc., Duluth, Ga.

[email protected]