Moving Ahead on Traceability

FOOD SAFETY & QUALITY

On January 4, 2011, President Barack Obama signed into law the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act, which, among other things, expands the authority of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to establish a product tracing system that will allow it to quickly track and trace foods as they move through the supply chain. The new law requires the FDA to initiate pilot traceability projects with the food industry by the end of September 2011, assess the costs and benefits of adopting tracing technologies, and report to Congress by mid-2012 with recommendations for establishing a product tracing system for food produced in or imported into the United States.

In my column “Resources for Product Traceability,” in the June 2008 issue of Food Technology, I wrote about U.S. and international organizations and their activities in the area of traceability. For this month’s column, I asked several major players for their views on advances and challenges regarding traceability.

In my column “Resources for Product Traceability,” in the June 2008 issue of Food Technology, I wrote about U.S. and international organizations and their activities in the area of traceability. For this month’s column, I asked several major players for their views on advances and challenges regarding traceability.

Professional Society: IFT

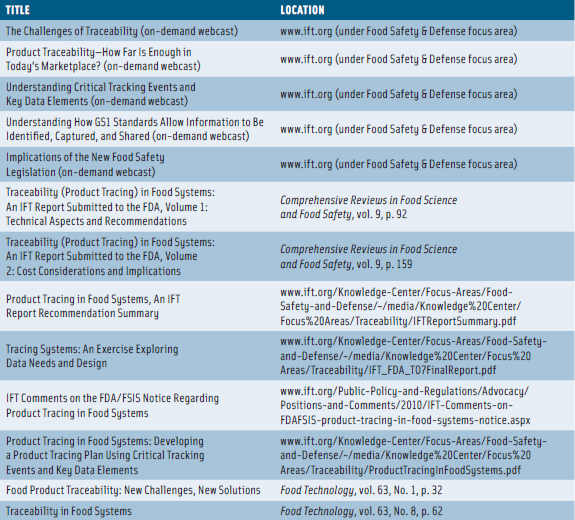

The Institute of Food Technologists (IFT) has been actively involved in promoting the establishment and use of food traceability systems for more than seven years, conducting conferences and workshops and issuing reports and documents (see Table 1). In 2008 the FDA commissioned IFT to evaluate product tracing systems and provide recommendations for a product-tracing system. IFT subsequently provided two documents to the FDA in 2009 under the overall title “Traceability (Product Tracing) in Food Systems: An IFT Report Submitted to the FDA.” The first document was subtitled “Technical Aspects and Recommendations,” and the second, “Cost Considerations and Implications.” Both documents were subsequently published in IFT’s Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety in 2010.

The Institute of Food Technologists (IFT) has been actively involved in promoting the establishment and use of food traceability systems for more than seven years, conducting conferences and workshops and issuing reports and documents (see Table 1). In 2008 the FDA commissioned IFT to evaluate product tracing systems and provide recommendations for a product-tracing system. IFT subsequently provided two documents to the FDA in 2009 under the overall title “Traceability (Product Tracing) in Food Systems: An IFT Report Submitted to the FDA.” The first document was subtitled “Technical Aspects and Recommendations,” and the second, “Cost Considerations and Implications.” Both documents were subsequently published in IFT’s Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety in 2010.

In March 2010, IFT submitted comments in response to an FDA/FSIS notice regarding product tracing in food systems. IFT also recommended guidelines for establishing a comprehensive system to track the movement of food products from farm to point of sale or service. The recommendations included creation of a standard list of key data or information to be collected (key data elements, or KDEs); standardization of formats for expressing the information; identification of the points along the supply chain, internally and between partners, where information needed to be captured (critical tracking events, or CTEs); comprehensive record-keeping that allowed the linking of information both internally and with partners; use of electronic systems for data transfer; inclusion of traceability as a requirement within audits; and required training and education on what compliance entails. The report concluded by saying that the system should be simple, user-friendly, and globally accepted as well as have the ability to leverage existing industry systems.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Earlier this year, in addition to the Food Safety Legislation Forum conducted in January, IFT and GS1 US commenced the educational series “Creating a Product Tracing Plan,” which was designed to provide food safety and supply chain professionals with the practical knowledge needed to develop and implement traceability programs within their organizations. The series consisted of webcasts on February 15 and March 15 and workshops on June 1 and 15.

Jennifer C. McEntire, Senior Staff Scientist and Director of Science and Technology Projects at IFT, said that many companies are offering traceability products and services (see Table 2). Some provide technology for marking products with barcodes and radio frequency identification (RFID) tags while others offer software to manage data sent to them by the food companies. The main drawback of some of these technology solutions, she said, is that they are proprietary and require everybody in the supply chain to subscribe to their service.

Jennifer C. McEntire, Senior Staff Scientist and Director of Science and Technology Projects at IFT, said that many companies are offering traceability products and services (see Table 2). Some provide technology for marking products with barcodes and radio frequency identification (RFID) tags while others offer software to manage data sent to them by the food companies. The main drawback of some of these technology solutions, she said, is that they are proprietary and require everybody in the supply chain to subscribe to their service.

![]() To overcome this problem, she said, solution providers can make their technologies interoperable by using international standards so that food and other companies using their technology solutions can be part of the standards system. To have a true traceability system, McEntire said, food companies need to have the right data to provide to these technology companies. The technology is there, but links haven’t quite been adopted, and they certainly don’t have universal adoption, she said. It’s really very complicated.

To overcome this problem, she said, solution providers can make their technologies interoperable by using international standards so that food and other companies using their technology solutions can be part of the standards system. To have a true traceability system, McEntire said, food companies need to have the right data to provide to these technology companies. The technology is there, but links haven’t quite been adopted, and they certainly don’t have universal adoption, she said. It’s really very complicated.

She said that many food companies don’t use third-party solution providers for a number of reasons. The Bioterrorism Act requires companies to be responsible for one-up/one-back tracing, and companies may feel that they can handle that internally. They are not required to care about traceability all across the supply chain. Why invest if they don’t have to and if competitors won’t? McEntire said that she’s not sure the motivation is really there right now.

Standards-Setting Organization: GS1 US

GS1 US (www.gs1us.org) is a not-for-profit, technology-neutral organization that promotes the use of GS1 standards in the United States. It was formed in 1974 by the grocery industry to help businesses adopt the universal product code (UPC). GS1 standards are now used globally to make the supply chain and electronic commerce more efficient through the use of standard product identification, barcodes, RFID tags, and electronic data interchange.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

GS1 US—the U.S. member organization of the international organization GS1—assigns unique company identifiers, which are the foundation for the global trade item numbers (GTINs) that identify items such as units, cases, and pallets; other applications support batch and lot numbers. The numbers can be encoded into a barcode or an RFID tag, allowing the information to be quickly and accurately read, captured, and stored. Numerous data-exchange standards help trading partners share information.

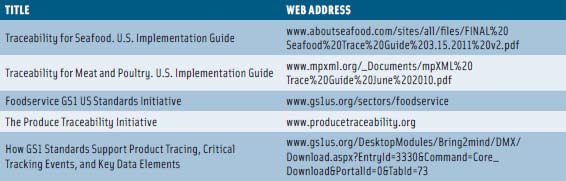

Steve Arens, Director of GS1 US, said that besides working with IFT on traceability educational efforts, the organization is actively involved in many traceability-related initiatives with the seafood, meat and poultry, produce, foodservice, dairy, deli, and bakery industries (see Table 3). Also, it has submitted comments to the FDA describing the potential use of GS1 standards to support product tracing.

Steve Arens, Director of GS1 US, said that besides working with IFT on traceability educational efforts, the organization is actively involved in many traceability-related initiatives with the seafood, meat and poultry, produce, foodservice, dairy, deli, and bakery industries (see Table 3). Also, it has submitted comments to the FDA describing the potential use of GS1 standards to support product tracing.

In addition, he said, a number of pilot projects are in the planning or execution stages with suppliers, retailers, distributors, and foodservice operators. Some are researching the identification of CTEs and determining how to enhance the information embedded in barcodes on their products while others are researching how to collect that information as products move through the supply chain to end users. This will lead to improved product traceability and supply chain visibility in the case of a recall or product withdrawal, he said, and the changes they make to enhance traceability may also enable them to reduce costs and operate more effectively.

However, he added, the potential changes to long-established business processes will require planning, investment, training, and potentially steep learning curves as companies try to keep their products flowing through the supply chain. And since a significant amount of U.S. food is imported, foreign suppliers and importers will need to be educated on the new requirements and regulations.

Foodservice View: Yum! Brands

Unified Foodservice Purchasing Co-op LLC (UFPC) (www.ufpc.com), which manages the supply chain for Yum! Brands, has been active in traceability since 2006. A project to standardize item numbering and barcode symbols has been managed as a cross-functional team representing each of the co-op’s restaurant brands—A&W, KFC, Long John Silver’s, Pizza Hut, and Taco Bell. The project’s intent is to replace existing manual processes with electronic data-capture systems.

According to Brenda Lloyd, Director of Equipment Purchasing & Distribution at UFPC, when the company wanted to establish a tracking system for its products, it found that while many solution providers felt they had an end-to-end system, there was no off-the-shelf program for capturing the data from an extended-data barcode that could then make it accessible for use in existing systems. There were several programs for setting up item-numbering systems, she said, and for creating and applying barcodes, and there were many back-of-house systems for using the data. But there was no standard software specifically for the foodservice industry for scanning GS1 standardized data.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Most of the company’s suppliers and distributors were using barcode systems for their own internal tracking but were not able to share the information across the supply chain electronically. Basically, Lloyd said, there was a gap between these two parts of the supply chain (i.e., GS1 bar codes being applied to the cases by suppliers and the ability to capture and utilize that data within different partners’ data-management systems). In 2010 UFPC began working with a mobility technology company to create a program that read the barcodes on its cases and uploaded the information to an above-store data cloud that could be accessed for potential use across the company’s supply chain.

The foodservice industry works hard to provide a safe supply chain, Lloyd said, and data standardization and electronic data capture will allow companies to document those measures faster and more precisely. There is a need for technology solutions that can be scaled to fit the needs of all sizes of operations throughout the foodservice industry. That means adopting and refining existing tools, not developing complex systems that cannot be adopted across all parts of the supply chain. The challenge ahead, she said, is for companies to continue to adopt industry standards and technology that would allow them to share data across all partners much more efficiently.

Supplier View: BASF

BASF Health & Nutrition (www.basf.com), a major supplier of food and feed ingredients, is using a traceability system that is on the verge of being implemented globally. The system, from a third-party solution provider, was chosen because of its interoperative capabilities and the ability to keep data behind the company’s firewall. Cristian Barcan, Sustainability and Traceability global project manager at BASF, said that one of the major challenges ahead for the food industry is to eliminate companies’ fear that traceability can only be done with a government-controlled database. That’s not the case, he said. Every single company can keep its own records and history.

The only thing needed to complete an entire traceability picture of a product in the supply chain, he said, is an identification number that is globally unique for each commodity at each step in the supply chain—one ID number at each step, telling what was done to or with it. Everything else—name, address, date, batch, production data, certificate of analysis, etc.—is just good business practice, which could be shared or not, depending on how transparent a company wants to be. The numbers are enough to provide a complete picture of what needs to be taken off the shelf in the case of a recall. A unique ID number using a standardized system such as the GS1 standards facilitates traceability, he said. So the only data a company needs to tell the outside world is a number, which means nothing to anybody but the company itself. Everything else about the product can be kept internal.

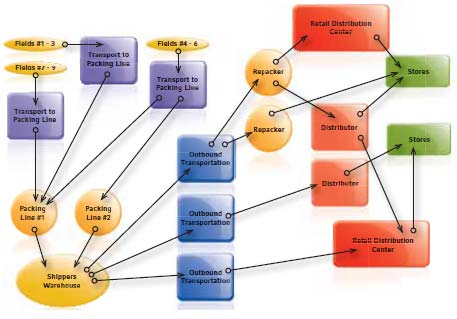

BASF is working with IFT on a project to show that it is possible to develop a traceability system without divulging company secrets, using various technologies. Simply maintaining and keeping records and barcodes doesn’t give traceability, Barcan said. Companies need to link the history of how a product was produced at all stages of the supply chain: which batches of raw materials went into the intermediate product, which batch of intermediate product went into which batch of product, which was recombined or repackaged, and so on all the way to the retail shelf.

One thing to understand, he said, is that traceability is a journey over time—it won‘t be accomplished overnight. But there are various steps companies need to take to get there, and as long as they take those steps they are going in the right direction.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Canada’s Experience: OnTrace

Canada’s federal and provincial agriculture ministers committed in 2009 to the creation of a national agriculture and food traceability system. Brian Sterling, Chief Executive Officer of OnTrace Agri-Food Traceability (www.ontrace.ca), said that because the first focus has been on livestock, with a few exceptions there is little coordination as yet between industry and government in Canada about produce and crop traceability.

Significant effort has been expended on developing common standards and the technological underpinnings of a national traceability system, he said, but a legislative framework must still be developed and may be two years away from becoming law. Partly to address the need for a focus on traceability, Ontario’s agriculture industry and government agreed to establish OnTrace Agri-Food Traceability, a not-for-profit corporation with a mandate to lead food traceability programs and initiatives in Ontario. Its goals, Sterling said, are to deliver traceability solutions that enable the agriculture and food industries in Ontario to become more innovative and competitive and to strengthen the capacity of industry and government to respond to emergencies related to agriculture and food welfare and public safety.

OnTrace has provincial responsibility to validate parcels of land associated with agrifood activities and assign them a unique premises identifier (PID) so that they can be rapidly located when necessary. OnTrace has partnered with GS1 Canada to couple these identifiers with Global Location Numbers. Premises registration is still voluntary.

In addition to registering premises, OnTrace recently announced its OnTrace Verified Network, which enables producers, processors, distributors, truckers, and retailers to share information to streamline their transactions and securely exchange critical information for recalls or emergencies. The network can deliver source verification of a food product across the whole food chain as well as provide the means for reliable, accessible, and low-cost electronic data exchange between businesses of any size.

Leaders in the agriculture and food sectors are pursuing their own interests in traceability, Sterling said. These are driven by market demand, either from Canadian consumers or from export market requirements. The need to verify the trail of food from farm gate to dinner plate and prove the origin of products is growing. Retailers, manufacturers, processors, and farmers are realizing that this is an issue that is not going to disappear and that they will need to work together to resolve it. Rugged independence is not a good thing when it comes to effective traceability, he said.

Sterling added that the challenges ahead for governments are similar to those for industry: creating a common direction and a collaborative process that implements a system that works for both government and industry. There is a consensus developing that government should provide the governance and enforcement of a Canadian traceability system while industry should operate the system.

The challenges at the supply end of the food chain—farmers and their immediate customers—revolve more around access to and use of electronic information-management tools, he said. Larger producers and industry leaders have played a role in encouraging others to embrace technology, he added. Cost is a factor, and governments have provided the programs to promote adoption. Now businesses need to decide that their future viability rests on more-effective use of business data for traceability and other purposes.

Neil H. Mermelstein, a Fellow of IFT and Editor Emeritus of Food Technology

[email protected]