Kitchen Capers

PACKAGING

Having wandered my own kitchen and a few others during the past and present, I have concluded that a surge of food packaging engineered explicitly for the 2013 home has erupted. The kitchen has been modernized with appliances and devices to assist the contemporary homemaker and family members. Granite and stainless steel are so common as to be considered a downside if home periodicals are to be believed. Energy transfer is controlled for perpetual human comfort and convenience. And, of course, food preservation, preparation, and delivery are complemented by continuous information via televisions and computers. It is difficult to determine which came first: the hardware or the packaged food to accommodate consumers in their kitchens. But what an array of targeted packaged food exists.

Timeliness has not necessarily been a factor in engineering and design for kitchen-friendly packaging. Often the combination has been decades in the making as with the rectangular cross section ketchup bottle to fit the refrigerator door shelf or microwave steamable pouches that currently pepper frozen food sections. Microwave popcorn and microwave steamable plastic pouches were developed in Raytheon laboratories during the RadaRange™ era of the 1950s and 1960s but did not burst onto the commercial scene until the late 1980s for popcorn and the 2000s for steamables. Of course, some brilliant engineering was required to graduate popcorn from primitive Kraft paper bags to susceptor-complemented greaseproof paper bags. And self-opening steamable packaging demanded some skillful comprehension of temperature sensitivity of pouch sealants after the discovery that internal steam generation complemented and accelerated microwave heating. These two examples are among a host of early integrations of thermodynamics with microwave ovens. Now, interactions are more carefully studied by packaging professionals to produce kitchen-friendly blends. The perception is that recent commercial successes presage a flood of food packages that are co-engineered to fit or enable preparation and consumption.

Refrigerators

Cooling and maintenance of reduced temperatures have been domestic mainstays since World War II with more built-in humidifiers, rapid chillers, ice and water dispensers, and special controls for meats. None of these superficially appears to warrant singular packaging for products but look again. Since the advent of supermarkets, fresh red meat has been offered in expanded polystyrene trays tightly wrapped in PVC stretch film. Since most red meat is frozen at home, the package structure fosters rapid cooling of the meat. When high-oxygen modified-atmosphere caseready packaged fresh red meat entered, the large primary package headspace created a thermal insulator that markedly slowed the freezing process and added freezer burn potential. Among the remedies was master packaging of multiple stretch-wrapped packages, which offered consumers an expected freezer-ready condition. Caseready fresh red meat packaging has yet to be universal for U.S. retailers; one issue is the interface with the freezer.

Some refrigerator makers have engineered low-temperature compartments especially for fresh red meat, claiming to reduce and maintain temperature at the freezing point (29°F), expecting that the entering packaged product would be at that temperature—a highly improbable occurrence. Might package thermal insulation promote this result?

Food packagers have increasingly designed bottles that fit neatly on refrigerator shelves. During the beginnings of polyester bottles for carbonated beverages, three-liter bottles that could not fit on any shelf were offered, but these were discontinued. Two-liter bottles that could stand on shelves became the standard. In the realms of wine and sauces, stand-up pouches and bag-in boxes are engineered for refrigerator shelves with dispenser spouts verhanging shelf edges; this allows rapid dispensing of liquid contents into cups and tumblers.

Food packagers have increasingly designed bottles that fit neatly on refrigerator shelves. During the beginnings of polyester bottles for carbonated beverages, three-liter bottles that could not fit on any shelf were offered, but these were discontinued. Two-liter bottles that could stand on shelves became the standard. In the realms of wine and sauces, stand-up pouches and bag-in boxes are engineered for refrigerator shelves with dispenser spouts verhanging shelf edges; this allows rapid dispensing of liquid contents into cups and tumblers.

Twelve-ounce aluminum cans of carbonated beverages or beer in multiples of six in plastic ring carriers were the original unitizers, but to move more liquid, multiples of ten, twelve, and 24 were introduced. With no direct links to the hardware, consumers were compelled to shelve the cans individually to fit them into the refrigerator or acquire a second beverage-only unit. This awkward situation was resolved with the Fridge Pak™, a paperboard 6 x 2 arrangement 12-pack that fit onto a shelf horizontally with a special corner opening that dispensed one can at a time. Because of its coated natural Kraft paperboard, the carton could be carried easily using a cross-grain handle and occupy relatively small space on refrigerator shelves. Winner of numerous awards, this interesting unitizer perhaps represented the beginning of the trend toward careful integration of appliance and package. The current issue is how multiples will be arranged and stored now that the trend is smaller and differentiated primary packages.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Ovens

Conventional gas or electric range tops and ovens have long been accommodated by aluminum foil pans, trays, bowls, and plates followed by dual ovenready (i.e., microwave plus convection) crystallized-polyester- and polyester-coated paperboard trays. Remember the classic TV dinner? Thrusting one into induction heated range tops requires special utensils, which could be met by packaging, but not enough induction units have been sold to warrant the introduction. Infrared units are a challenge for packaging as are the forced convection ovens and combination microwave/convection units that are gradually gaining momentum. My view is that the time of the conventional food heater has passed in favor of the microwave oven and the small appliance.

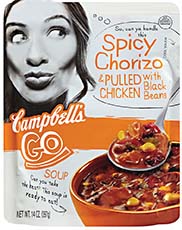

Society is comfortably in the era of three-minute re-thermalization of ambient temperature shelf-stable barrier plastic cans with overcap to release steam pressure; thermally insulated expanded polystyrene labels for soups, sauces, entrees, and whatever else; retort barrier plastic trays, bowls, and cups with handles for hand holding; stand-up plastic pouches for soups with thumb and finger holds to facilitate grasping hot pouches; and the rapidly emergent chilled meals and side dishes in polypropylene trays and bowls.

Society is comfortably in the era of three-minute re-thermalization of ambient temperature shelf-stable barrier plastic cans with overcap to release steam pressure; thermally insulated expanded polystyrene labels for soups, sauces, entrees, and whatever else; retort barrier plastic trays, bowls, and cups with handles for hand holding; stand-up plastic pouches for soups with thumb and finger holds to facilitate grasping hot pouches; and the rapidly emergent chilled meals and side dishes in polypropylene trays and bowls.

Microwave susceptor laminated paperboard sleeves for hand-held turnover sandwiches such as Hot Pockets™ or frozen pizza or bread represent the epitome of linking microwave energy with the package. Microwave energy heats both the filling and the susceptor film, which in turn heats the surface to crisp and brown. Whether the rolled sandwich trend was led by Hot Pockets or the product rode a rising wave of wraps, enchiladas, calzones, roll-ups, turnovers, knishes, and other similar items, popularity will be a subject of culinary chronology, but the result is no longer a phenomenon; it is mainstream.

Although a visit to Bed, Bath and Beyond or analogous retailer will present a vast variety of food heating devices such as steamers, woks, rice cookers, waffle irons, slow cookers and so on, the core small appliance remains the toaster/toaster oven. The world’s food marketers have definitely developed countless products designed for radiant heating and surface crisping of items such as Pop Tarts® and the like. Most are configured to be heated outside of the package, but some are engineered for heating within a heat-resistant package for quick temperature rise. A simple device designed to toast bread is now married to a host of food products formulated explicitly for the appliance.

Coffee Brewing

Many western movies invariably featured cowhands on the prairie boiling water and coffee grounds over the campfire near the chuck wagon. And sitcoms always showed a family pouring coffee beverage from a percolator or similar coffee brewer, which has been followed by porous paper filters containing premeasured portions of ground coffee that fit the brewing device. Then came the era of roasted coffee beans in barrier flexible pouches with one-way valves to allow for expulsion of carbon dioxide, for the grinding of beans just before brewing.

Perhaps history’s most extraordinary example of the intimate marriage of food product, kitchen appliance, and package is the single-cup coffee maker. Less than 20 years old, this combination is probably the most expensive means of offering a single cup of the beverage to consumers: an electronic water heater plus a single-cup unit portion of ground roasted coffee in a barrier plastic heat-sealed thermoform. To prepare a single cup, the thermoform is inserted into the appliance, which is activated to force perfect temperature water through grounds in the instantly pierced thermoform. The plastic unit is then discarded. For about fifty cents, a perfect cup of coffee has been prepared for the coffee drinker.

Perhaps history’s most extraordinary example of the intimate marriage of food product, kitchen appliance, and package is the single-cup coffee maker. Less than 20 years old, this combination is probably the most expensive means of offering a single cup of the beverage to consumers: an electronic water heater plus a single-cup unit portion of ground roasted coffee in a barrier plastic heat-sealed thermoform. To prepare a single cup, the thermoform is inserted into the appliance, which is activated to force perfect temperature water through grounds in the instantly pierced thermoform. The plastic unit is then discarded. For about fifty cents, a perfect cup of coffee has been prepared for the coffee drinker.

Consider the variables: cost is significantly greater than for multi-cup brewing, but a wide variety of flavors—more than 200—is now offered at retail. Time for preparation is hardly different from conventional pot brewing. No grinding is required. No handling of wet grinds, but a few grams of multilayer barrier plastic enters the solid waste stream each time. The consumer gains what he/she perceives as a simple, clean means of receiving a gourmet beverage. Prior to 1995, was there any hint of single-cup coffee making in any peer-review or popular literature? For those technologists and marketers whose task it is to envision the future, did anyone have the chutzpah to predict any success for an exclusive combination of a $150 small appliance and prepackaged half-dollar-priced unit portions of ground coffee?

What home food preparation activity of today might a food packaging technologist dare to address with a high cost package plus a new and expensive single-purpose device? A rice cooker that bypasses instant rice and retort packaged rice are in America’s home kitchens. The water dispenser is usurping bottled water. Might the beverage carbonator be the phenomenon of tomorrow? The message today is that he/she who studies the ethnography of today’s consumer is destined to see the future, which is inevitably a tight linkage of product and package.

Aaron L. Brody, Ph.D., CFS,

Aaron L. Brody, Ph.D., CFS,

Contributing Editor

President and CEO, Packaging/Brody Inc., Duluth, Ga.,

and Adjunct Professor, University of Georgia

[email protected]