Choosing an Allergen Test Kit

FOOD SAFETY AND QUALITY

Food allergies are immune reactions to food proteins. More than 90% of all food allergies are caused by eight foods: peanuts, soybeans, milk, eggs, fish, shellfish, tree nuts, and wheat. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires declaration of the presence of these eight allergens on labels of food products under its jurisdiction. The U.S. Dept. of Agriculture does not require such listing on meat and poultry products but encourages similar declaration. The FDA allows only foods containing less than 20 ppm of gluten to be labeled as gluten-free, but the declaration of gluten-containing grain ingredients by source is required in some cases—even with levels below 20 ppm. Gluten is never declared in the ingredients list unless the ingredient is vital wheat gluten; instead, the common or usual name of the gluten-containing ingredient is used (e.g., wheat flour, barley malt, etc.). The European Food Safety Authority requires labeling of 14 foods that cause most allergies and intolerances: milk, eggs, peanuts, soy, tree nuts, fish, shellfish, celery, mustard, sesame seeds, lupin, cereal sources of gluten, sulfur dioxide, and sulfites. Other countries require labeling for other specific food allergens.

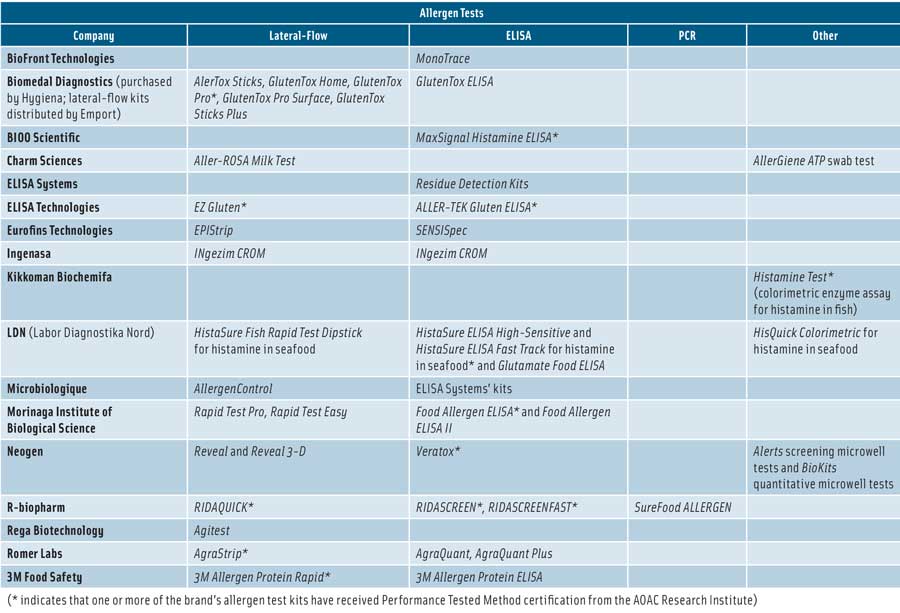

It is important for food companies to monitor whether their food products contain or may contain allergens—either from their use as ingredients or as a result of insufficient sanitation or cross-contamination. To help in this effort, manufacturers have developed test kits for detection and measurement of food allergens. Test kits are commercially available for almonds, beta-lactoglobulin, barley gluten, Brazil nut, buckwheat, casein, cashew, celery, coconut, crustaceans/shellfish, egg, egg white, egg yolk, fish, gliadin, glutenin, gluten, hazelnut, lupin, lysozyme, macadamia nut, milk, mollusks, mustard, ovalbumin, peanut, pecan, pine nut, pistachio, rye gluten, sesame, soy, tree nuts, walnut, wheat gluten, and whey protein. Kits are also available for detecting substances to which some people are intolerant, including histamine, sulfite, and glutamate.

It is important for food companies to monitor whether their food products contain or may contain allergens—either from their use as ingredients or as a result of insufficient sanitation or cross-contamination. To help in this effort, manufacturers have developed test kits for detection and measurement of food allergens. Test kits are commercially available for almonds, beta-lactoglobulin, barley gluten, Brazil nut, buckwheat, casein, cashew, celery, coconut, crustaceans/shellfish, egg, egg white, egg yolk, fish, gliadin, glutenin, gluten, hazelnut, lupin, lysozyme, macadamia nut, milk, mollusks, mustard, ovalbumin, peanut, pecan, pine nut, pistachio, rye gluten, sesame, soy, tree nuts, walnut, wheat gluten, and whey protein. Kits are also available for detecting substances to which some people are intolerant, including histamine, sulfite, and glutamate.

Allergen Detection Methods

Lateral-flow tests, also known as immunochromatographic assays, are usually available in strip or dipstick format and generally provide qualitative results. When the sample is applied to the strip, it mixes with a colored reagent and moves by capillary action along the strip into specific zones that contain the allergen-specific antibody. If the allergen is present, it will bind to the antibody, and a visible line will form. A control zone is usually included that will form a color indicating that the strip has worked correctly.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) provide quantitative results and are the most widely used method for the detection and quantification of food allergens. The most common form is the sandwich ELISA. Protein in a sample is extracted and added to the antibody-coated wells of a microplate, forming an antigen-antibody complex. Then a second allergen-specific antibody linked to an enzyme is added. The enzyme-linked antibody (conjugate) binds to the antigen-antibody complex, forming an antibody-antigen-antibody sandwich. An enzyme substrate that changes color in the presence of the conjugate (and thus the allergen) produces a color whose intensity is directly proportional to the concentration of the protein in the food. Some food matrices can interfere or cause cross-reactions with other allergens, and some ELISAs may not be suitable for cooked products since the protein molecules may be denatured and no longer detectable but can still cause allergic reactions.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests detect the DNA of an allergen rather than the protein itself and is more sensitive than ELISAs. They can be used for testing cooked products because DNA generally remains intact after being exposed to cooking temperatures. They are also not subject to the interferences ELISAs are subject to, but they can’t be used on products that don’t contain DNA, such as oil, milk, and egg white.

Additionally, swab tests, such as those that detect adenosine triphosphate (ATP) or protein in general provide qualitative assessment of cleanliness of equipment surfaces. These tests, as well as PCR tests, can be referred to as surrogate tests because they do not detect a specific source of protein. Mass spectrometry is also being considered as an allergen-detection method because it can identify fragments of proteins even if they have been degraded by processing.

Expert Q & A on Allergens

Q: How do the test kits for a specific food allergen differ among the companies providing the tests?

Steve Taylor, a professor in the department of food science and technology at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and co-director of the university’s Food Allergy Research & Resource Program, said that kits can have different targets and food companies need to know which target best fits their product. For example, one kit manufacturer might have a milk test that targets beta-lactoglobulin whereas another might target a specific casein.

Tony Lupo, director of technical service at Neogen, said that there are three primary areas where allergen test kits can vary from supplier to supplier. The first is the antibody itself. Considerations include specificity of the antibody to the target allergenic food and whether it cross-reacts with closely related proteins, how sensitive the antibody is (to what level the allergenic food can be detected), and in what form the allergenic food can be detected (will the antibody detect the allergen after the food is roasted, baked, retorted, fried, extruded, hydrolyzed, etc.?). The second is how the extraction conditions of a test kit will affect the solubility and thus the detectability of the target allergen. If a target protein is not soluble, he said, it won’t be detected. And the third is the standard chosen to calibrate any test kit, which is critical to understanding how to interpret the data being generated. All test kits express results in parts per million (ppm), he said, but some express results in ppm of allergenic food, others in ppm of protein from the food, and still others in ppm of a specific fraction of protein from the food. For example, of three test kits testing for milk allergen, one could express the limit of quantitation as 2.5 ppm of nonfat dry milk, another as 0.9 ppm of milk protein, and a third as 0.72 ppm of casein, but they are all equivalent in sensitivity.

Tony Lupo, director of technical service at Neogen, said that there are three primary areas where allergen test kits can vary from supplier to supplier. The first is the antibody itself. Considerations include specificity of the antibody to the target allergenic food and whether it cross-reacts with closely related proteins, how sensitive the antibody is (to what level the allergenic food can be detected), and in what form the allergenic food can be detected (will the antibody detect the allergen after the food is roasted, baked, retorted, fried, extruded, hydrolyzed, etc.?). The second is how the extraction conditions of a test kit will affect the solubility and thus the detectability of the target allergen. If a target protein is not soluble, he said, it won’t be detected. And the third is the standard chosen to calibrate any test kit, which is critical to understanding how to interpret the data being generated. All test kits express results in parts per million (ppm), he said, but some express results in ppm of allergenic food, others in ppm of protein from the food, and still others in ppm of a specific fraction of protein from the food. For example, of three test kits testing for milk allergen, one could express the limit of quantitation as 2.5 ppm of nonfat dry milk, another as 0.9 ppm of milk protein, and a third as 0.72 ppm of casein, but they are all equivalent in sensitivity.

Kurt Johnson, president of R-Biopharm, said that test kits from different suppliers use different antibodies; are calibrated to different standards; and can vary in detection range, limit of detection, limit of quantitation, time for the test, and extraction procedures. And Matthew Lawless, technical support specialist at Romer Labs USA, said that many lateral-flow devices must be stored at refrigerated temperatures and warmed to room temperature prior to use while others can be stored at room temperature, which is an advantage in making unscheduled emergency and otherwise impromptu testing quick and efficient. He said that lateral-flow kits and ELISA kits both differ in the time it takes to get results and in the limit of detection. The heart of the difference between ELISA kits, he said, is the antibody used to target a specific allergenic protein. Some companies offer gluten test kits that use the G12 antibody, which is specific to the most immunotoxic portion of wheat gliadin responsible for eliciting negative effects in celiac patients, while other companies use the R5 antibody, which is specific to rye secalin and merely cross-reacts with wheat gluten. As another example, the peanut contains several allergenic proteins (Ara h 1, Ara h 2, etc.), and it is up to the kit manufacturer which allergenic proteins the kit will detect.

Another way that ELISA kits can be differentiated, Lawless said, is the calibration material the kits are standardized against. With the lack of a specified reference material, each kit manufacturer uses its own material to create calibrators; this often leads to differing reporting units. For example, milk may be reported in units of milk, milk protein, nonfat dry milk, beta-lactoglobulin, casein, etc.

Q: How should a food company choose which type of test to use?

Taylor said that users have the responsibility to determine that the test method is “fit for purpose”( i.e., that it works on the form of the food that they’re trying to detect and provides the type of result desired, qualitative or quantitative). He said that ELISAs detect a specific protein, PCR detects DNA from a specific source, mass spectrometry methods detect a specific target, ATP tests detect ATP from all biological sources and are not specific, and general protein methods don’t discriminate among various sources of protein.

Lupo said that method choice will depend on the type of information users hope to gain. If an allergen management program is in place and validated and the desire is to verify that the program is functioning properly, lateral flow is an ideal solution because it screens above or below a particular threshold. If an allergen management program is in the validation or revalidation stage, a fully quantitative solution by ELISA would be preferred. Also, where a free-from allergen claim is being made, the finished product should be tested with a fully quantitative method like ELISA. He said that PCR would not be his preferred approach since it relies on a genetic target and genetic material can be present without correlating to allergen protein. He would reserve PCR for situations in which an effective immunological method like lateral flow or ELISA does not exist.

Johnson said that a customer needs to match the application to the type of testing. Lateral-flow devices are predominately used for sanitation and cleaning validation. ELISAs are used for ingredients and finished product, especially when a threshold number is available (currently only for gluten). PCR is generally used where no ELISA exists and for dispute mediation when ELISA results are either not within expectations or two different ELISAs give different results.

Lawless said that ELISAs are suited for most companies willing to invest in in-house testing. Companies then have the ability to set their own internal thresholds and can design, implement, and verify their own sanitation standard operating procedures. However, many companies do not have the time, manpower, or funds to invest in ELISA methods because they require more sophisticated equipment and training. Lateral-flow tests offer onsite testing that requires no extra equipment. They provide a simple yes-or-no answer for allergen detection, and users can easily send their samples to a third-party lab for quantitative results if necessary.

Q: Since many companies offer a test kit for the same allergen, how should a food company choose which company’s test kit to use?

Q: Since many companies offer a test kit for the same allergen, how should a food company choose which company’s test kit to use?

Taylor said that the company should make sure that the kit detects residues of the allergen in the form that is appropriate. For example, if a company is deep-fat frying and wants to detect milk in the fried food, will they get good detection once the product has been through the frying process?

Lupo said that users should ensure that any kit is tested on known dirty surfaces or with known allergen-containing samples and elicits a positive result to ensure that the method is fit for purpose and that the product processing does not affect the test kit’s ability to detect the target. Users should also ensure that the kit’s time requirements and procedure fit the company’s laboratory workflow.

Johnson said that any decision should be based on the correct balance of external validation, in-house validation, cost, time for assay, ease of use, and confirmation of complex or unusual matrices.

Lawless said that each company’s test kits have unique advantages. So deciding which test kit to use goes beyond just the kit itself to the provider’s capabilities and services, such as technical support, involvement in the customer’s food-testing program, training, and analytical testing.

Neil H. Mermelstein, IFT Fellow,

Neil H. Mermelstein, IFT Fellow,

Editor Emeritus of Food Technology

[email protected]