Eating Healthier in School

School feeding programs must meet federal nutrition guidelines, but less-nutritious ‘competitive’ foods also sold in schools do not have to. Here’s what should be done.

One can hardly read an article about obesity in children in either the popular press or the scientific peer-reviewed literature and not see the words “school lunch” somewhere in the article. But is this connection warranted? Let’s take a close look at school meals in the United States.

Value of School Feeding Programs

Value of School Feeding Programs

More than 100 years ago, in 1894, the Starr Center Association in Philadelphia started serving penny lunches in one school. This was soon expanded to a second school. A lunch committee was established, and lunches were extended to include nine schools in the city. Soon after, other cities and other schools started serving lunches to students.

However, school lunch was not a federally mandated program until President Harry S. Truman signed the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act, a federal law, on June 4, 1946. The legislation came in response to claims that many American men had been rejected for World War II military service because of diet-related health problems. The federally assisted meal program was established as a “measure of national security, to safeguard the health and well-being of the Nation’s children and to encourage the domestic consumption of nutritious agricultural commodities.” This Act authorized the National School Lunch Program. Although the Act has been amended numerous times, the basic framework of the program still exists.

The U.S. Dept. of Agriculture is responsible for the Child Nutrition Programs, which include the National School Lunch Program (NSLP), the School Breakfast Program, the Child and Adult Care Food Program, and the Summer Food Service Program. Together, these programs account for a quarter of USDA’s food assistance outlays and provide about 30 million children with healthy meals on a regular basis. The National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs are entitlement programs. Public and nonprofit private schools of high school grade or under and public or nonprofit private residential child care institutions may participate in these programs. School districts and independent schools that choose to participate get cash subsidies and donated commodities from USDA for each meal they serve. They must serve meals that meet federal requirements and must offer free or reduced-price meals for eligible students.

The regulations mandate that school lunches provide one-third, and school breakfasts one-fourth, of the 1989 Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for protein, calcium, iron, vitamin A, vitamin C, and energy for specific age or grade groups. The NSLP also mandates that lunch must average no more than 30% of calories from fat and no more than 10% of calories from saturated fat (Pilant, 2006). Meals are measured for compliance on a weekly basis. Schools have the option of deciding which of four different menu-planning options they will follow to meet federal and state legislative requirements. The NSLP also offers after-school snack programs and summer feeding programs in sites that meet eligibility requirements.

Gleason and Suitor (2001) have shown that, students participating in the NSLP have significantly higher intakes of vegetables than nonparticipants (1.3 servings consumed at lunch vs 0.6) and milk (0.8 servings vs 0.2), and have lower intakes of sugar-sweetened beverages (0.3 servings vs 0.7).

Most U.S. school-aged children attend school. Estimates suggest that the share of food consumed at schools ranges from 19% to 50% or higher. Today, about 95% of U.S. children have access to the federally regulated NSLP meals. Although the meals are nutritionally balanced, many students, for a variety of reasons, choose not to participate. Although the percentage of participating students varies greatly across the country, less than half of the high school students who could participate in the NSLP probably do so on a regular basis. Even with this level of participation, the NSLP serves 28 million lunches daily, and approximately 8.9 million students receive breakfast in the School Breakfast Program (Story et al., 2006).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

School meal programs are regarded as a safety net for ensuring that children and adolescents at risk for poor nutritional intakes have access to a safe, adequate, and nutritious food supply that promotes optimal physical, cognitive, and social growth and development. Approximately 60% of children who eat school meals come from low-income families. For these children, the NSLP helps protect against hunger.

School meal programs significantly improve school-age children’s diets. Gleason and Suitor (2001) showed that students who participated in the NSLP were almost twice as likely to report eating vegetables at lunch and consuming more fruits than children who did not participate (73% vs 40% and 48% vs 32%, respectively). Students who did not eat NSLP meals were three times more likely to report sugar consumption (sweetened beverages and sweets) than NSLP students (64% vs 21%).

Cullen and Zakeri (2004) considered the change in dietary habits that occurred when students transitioned to middle schools where there was access to a snack bar or a la carte meals and student stores. Traditionally top-selling snack bar foods such as pizza, chips, soda, French fries, candy, and ice cream are high in fat and calories. In this study among fifth-grade students, those who selected only the NSLP lunch consumed 0.8 servings of fruits and vegetables, compared to 0.4 servings for those who chose only snack bar foods for lunch and 0.2 servings for those who brought their lunches from home. The students who selected the NSLP lunch had fruit and vegetable consumption totals similar to those of fourth-grade students who selected the NSLP lunch.

Overall, middle school children who gained access to school snack bars consumed fewer healthy foods than in the previous school year when they were in elementary schools and only had access to lunch meals served at schools. The authors concluded that schools should provide healthy food choices and require healthier foods at school snack bars.

Problem of Competitive Foods

However, there are foods available in schools that are not part of the federally regulated school meals. The availability of high-fat, high-sugar foods and beverages in schools often creates a food environment that invites excess energy intake and excess weight gain (Mello et al., 2006). Competitive foods are defined as any foods sold in competition with the NSLP. They can be divided into two categories: “foods of minimal nutritional value” and all other foods offered for individual sale.

A food of minimal nutritional value is defined as a food that provides less than 5% of the RDA of each of the eight specified nutrients—protein, vitamin A, vitamin C, niacin, riboflavin, thiamin, calcium, and iron—per serving. Four categories of foods are prohibited: soft drinks, water ices, chewing gum, and certain candies. Minimally nutritious foods and beverages are prohibited from being sold in foodservice areas during the breakfast and lunch periods.

Other foods and beverages offered for individual sale—ranging from second servings of the school meal to foods that are purchased in addition to or in place of the school meal or from vending machines, school stores, and snack bars—are subject to less regulation. Examples include ice cream, chips, and crackers.

A school district may decide to allow the sale of these foods where food is prepared, served, and eaten during the meal periods only if all income from the sale of these foods benefits the nonprofit school foodservice or the school or school-approved student organizations. Although school breakfasts and school lunches must meet federal nutrition standards, competitive foods are exempt from such requirements. Even though there are regulations specifically addressing foods of minimal nutritional value, these foods can be still made available for students throughout the day. Vending machines could be placed outside the cafeteria door to sell sugar-sweetened beverages. School groups may raise funds by selling candy or other food items before, during, or after school. The cafeteria could contract with a fast-food company to sell its branded items.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

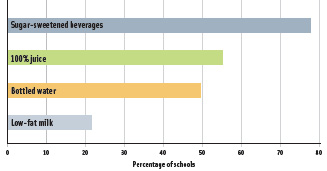

Here are some statistics about competitive foods: • Vending machines, school stores, or snack bars are present in 43% of elementary schools, 74% of middle schools, and 98% of high-schools nationwide. Percentages of items available from these sources are shown in Figure 1.

• Vending machines, school stores, or snack bars are present in 43% of elementary schools, 74% of middle schools, and 98% of high-schools nationwide. Percentages of items available from these sources are shown in Figure 1.

• A la carte foods constitute at least half of all food sales in about one-third of schools offering this option. In some schools, a la carte sales provide 70% of total lunchtime revenue.

• Only 10% of “chips and crackers,” the largest category of a la carte foods available, provide low-fat options.

• Fruits and vegetables represent only 4.5% of a la carte options.

• At least 20% of U.S. schools sell brand-name fast food to students on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis (Fox et al., 2005).

• There are limited portion-size guidelines for competitive foods. Soft drinks can be found in 20-oz containers in some school vending machines.

• Food fundraisers directly compete with the school foodservice department and are subject to no nutritional standards.

Schools and districts often rely on income from competitive food sales, including vending machines, primarily from sugar-sweetened soft drinks but also from bottled water, to support discretionary spending not related to school foodservice. Over the past few years, more districts have reported exclusive agreements with beverage companies or other companies. In 2003–04, nearly half of all schools had an exclusive beverage contract, often covering five years or more. Many “pouring rights” contracts increase the share of profits schools receive when sales volume increases. Thus, there is an incentive for the schools to increase the sales of vending-machine beverages. Companies may also advertise on scoreboards, in hallways, on book covers, and elsewhere.

What Should Be Done

School foodservice programs were traditionally regular line items in local school budgets. Now more often, the school foodservice must be completely self-supporting and cover costs of food, labor, and other expenses, such as equipment, utilities, and trash removal. Budget pressures often force schools to sell popular but less-nutritious foods a la carte. However, public discomfort and questions about the school food environment is growing. School administrators and concerned citizens are questioning whether schools can provide more-healthful food options that are acceptable to students and provide a revenue stream. Limited evidence shows that they can. Although some say that federal nutrition regulations are inadequate, the regulations permit state and local authorities to impose additional restrictions.

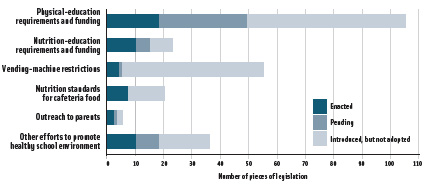

Within state courts and legislatures and local governments, there has been an increase in legal initiatives to combat obesity and provide healthier environments for children. Much of the focus has been on schools (NCSL, 2006; Weiss and Smith, 2004). About 60% of U.S. middle schools and high schools sell soft drinks from vending machines on the school grounds. In response to the interest in promoting healthier schools, states and school boards have developed policies to reduce students’ access to foods that are not nutritious and to promote physical activity opportunities for students. Measures include laws restricting competitive food sales, closed-campus policies that keep students at school for lunch, and vending machine restrictions (Figure 2). There are also increased pressures for individual schools and districts to carefully consider issues related to school meals.

Within state courts and legislatures and local governments, there has been an increase in legal initiatives to combat obesity and provide healthier environments for children. Much of the focus has been on schools (NCSL, 2006; Weiss and Smith, 2004). About 60% of U.S. middle schools and high schools sell soft drinks from vending machines on the school grounds. In response to the interest in promoting healthier schools, states and school boards have developed policies to reduce students’ access to foods that are not nutritious and to promote physical activity opportunities for students. Measures include laws restricting competitive food sales, closed-campus policies that keep students at school for lunch, and vending machine restrictions (Figure 2). There are also increased pressures for individual schools and districts to carefully consider issues related to school meals.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

The Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 requires local education agencies that participate in USDA’s Child Nutrition Programs to develop local wellness policies beginning in the 2006–07 school year. The wellness policies are required to include goals for nutrition education, nutrition guidelines for all foods available on school grounds throughout the school day, and physical activity guidelines, and to develop a plan to measure implementation. Parents, students, school food authorities, school boards, school administrators, and the public are to provide input in the establishment of the wellness policies.

Several interventions have changed school food environments, e.g., by reducing the fat content of food in vending machines and making more fruits and vegetables available (Bartholomew and Jowers, 2006; Probart et al., 2006; Templeton et al., 2005). Interventions are just beginning to target the availability of competitive foods. Some studies have shown that there is no significant change in revenue from a la carte items when more healthful, tasty, and attractive options are provided.

Changing behaviors requires creating awareness of the problems and the solutions. Advocates, administrators, parents, teachers, health professionals, and students themselves have opportunities to advocate and promote healthy school environments. Opportunities and challenges abound:

• Encourage USDA and state and local educational authorities to develop, implement, and monitor nutrition standards for competitive foods and beverages.

• Establish pilot programs to expand school meal funding in schools with a high percentage of students with a high risk for being overweight.

• Encourage state and local educational authorities to develop, implement, and enforce school policies to make schools advertising-free to the greatest extent possible.

• Encourage and support the involvement of a wide range of stakeholders in the development of evidence-based community and school wellness policies.

• Consider ways to foster participation in the School Breakfast Program.

• Support requirements for more and better physical programs in schools for all students.

• Make certain that the amount of time allocated to meals and physical activity programs is adequate.

• Support changing food and beverage contracts to include more healthful foods and beverages.

• Encourage fund-raising activities that support rather than undermine student health.

• Involve students in setting nutrition standards, suggesting healthful foods to be incorporated in schools and using marketing techniques to promote healthy foods.

• Foster continuity between the health and nutrition messages that students receive in classes and the school cafeteria.

by Marilyn A. Swanson, Ph.D., R.D., a Fellow and Professional Member of IFT, is CSREES National Program Leader for Maternal and Child Health at the USDA/ARS Children’s Nutrition Research Center, Houston, Tex. ([email protected])

References

Bartholomew, J.B. and Jowers, E.M. 2006. Increasing frequency of lower-fat entrees offered at school lunch: An environmental change strategy to increase healthful selections. J. Am. Dietet. Assn. 106: 248-252.

Cullen, K.W. and Zakeri, I. 2004. Fruits, vegetables, milk, and sweetened beverages consumption and access to a la carte/snack bar meals at school. Am. J. Pub. Health 94: 463-467.

Fox, S., Meinen, A., Pesik, M., Landis, M., and Remington, P.L. 2005. Competitive food initiatives in schools and overweight in children: A review of the evidence. WMJ . 104(5): 38-43.

Gleason, P. and Suitor, C. 2001. Children’s diets in the mid-1990s: Dietary intake and its relationship with school meal participation. Rept. CN-01-CD1, Special Nutrition Programs, Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Alexandria, Va.

Mello, M.M., Studdert, D.M., and Brennan, T.A. 2006. Obesity—The new frontier of public health law. New Eng. J. Med. 354: 2601-2610.

NCSL. 2006. State legislative initiatives to combat obesity in schools, 1998–2005. Data from the Health Promotion Program state legislation and statute database: Obesity, obesity-childhood, physical activity, and nutrition. www.ncsl.org/programs/health/phdatabase.htm, accessed Aug. 15.

Pilant, V.B. 2006. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Local support for nutrition integrity in schools. J. Am. Dietet. Assn. 106: 122-133.

Probart, C., McDonnell, E., Hartman, T., Weirich, J.E., and Bailey-Davis, L. 2006. Factors associated with the offering and sale of competitive foods and school lunch participation. J. Am. Dietet. Assn. 106: 242-247.

Story, M., Kaphingst, K.M., and French, S. 2006. The role of schools in obesity prevention. Future Child 16(1): 109-142.

Templeton, S.B., Marletter, M.A., and Panemangalore, M. 2005. Competitive foods increase the intake of energy and decrease the intake of certain nutrients by adolescents consuming school lunch. J. Am. Dietet. Assn. 105: 215-220.

Weiss, R.I. and Smith, J.A. 2004. Legislative approaches to the obesity epidemic. J. Pub. Health 25: 379-390.