Challenges to Food Science in the U.S.

Undergraduate food science programs in the United States are facing declining enrollments that could lead to a shortage of food scientists, but efforts are underway to increase recruitment.

The core knowledge area of the food processing industry is food science. Food science and agricultural science are high-impact occupational areas critical to a nation’s self-dependence, security, and economic viability. Professionals educated and trained in these sciences cater to the large production and manufacturing sectors as well as the knowledge and service sectors of the economy. Leading food and agricultural companies derive significant revenue through the knowledge economy, characterized by patent royalties, product licensing, and business, professional, and technical services. The knowledge sector also enables companies in the food and agricultural sciences to become pioneers and leaders in their industry segments and to develop products in a competitive and dynamic global marketplace.

Companies aspiring to compete in the newly emerging global economic matrix should possess a workforce that is trained to adapt and perform high-skilled tasks. Its workers must be able to bring to the workplace technical and educational skills, manufacturing efficiency, resourcefulness, creativity, knowledge of other cultures, the ability to interact and communicate with diverse clientele, and the motivation to apply their skills in the global marketplace.

In a recent report (NAS, 2006) requested by Congress, the National Academy of Sciences concluded that the U.S. leadership in the global knowledge market and in science and technology was beginning to erode. The report calls for an urgent, comprehensive, and coordinated federal effort to bolster competitiveness in education and focus efforts toward leadership in science and technology.

Among four major recommendations to counter the erosion in scientific pre-eminence, the report makes two human resource recommendations for federal policy-makers: (1) Increase America’s talent pool by vastly improving K-12 mathematics and science education, and (2) Develop, recruit, and retain top students, scientists, and engineers from both the U.S. and abroad.

Profession Faces a Shortage

In a recent effort to determine the status of food science education in the United Kingdom, an independent project was initiated by the Institute of Food Science and Technology (IFST), the UK-based professional body for Food Science and technology), the Food & Drink Sector Skills Council, and the Science Council (IFST, 2006). Results of the study have raised concerns about the food science knowledge infrastructure in the UK.

Applicants for food science degree courses in the UK have more than halved in the past decade. More than half of employers surveyed reported a shortage of qualified food science personnel, and recruitment times to fill food science vacancies spanned 2–3 years. IFST warns that declining numbers of qualified graduates entering the food industry is seriously threatening the UK food industry’s ability to meet the needs for further growth (Fletcher, 2006).

In a similar situation, the areas of food science and agricultural science in the U.S. are also projected to experience a shortage of qualified labor. A joint report published by the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture and Purdue University (Gilmore et al., 2006) estimates that slightly more than 52,000 annual job openings will be available during 2005–10 for new college graduates in the U.S. Food, Agricultural, and Natural Resources system. Some 49,300 qualified graduates will be available each year for these positions, thereby leaving about 2,700 unable to be filled by qualified graduates.

Service and knowledge occupations requiring an education in food science, such as food quality assurance, technical sales, nutraceuticals development, biomaterials engineering, public health administration, food safety and food system security, and consumer information technologies, are specifically mentioned in the report.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Food Science Degrees Declining

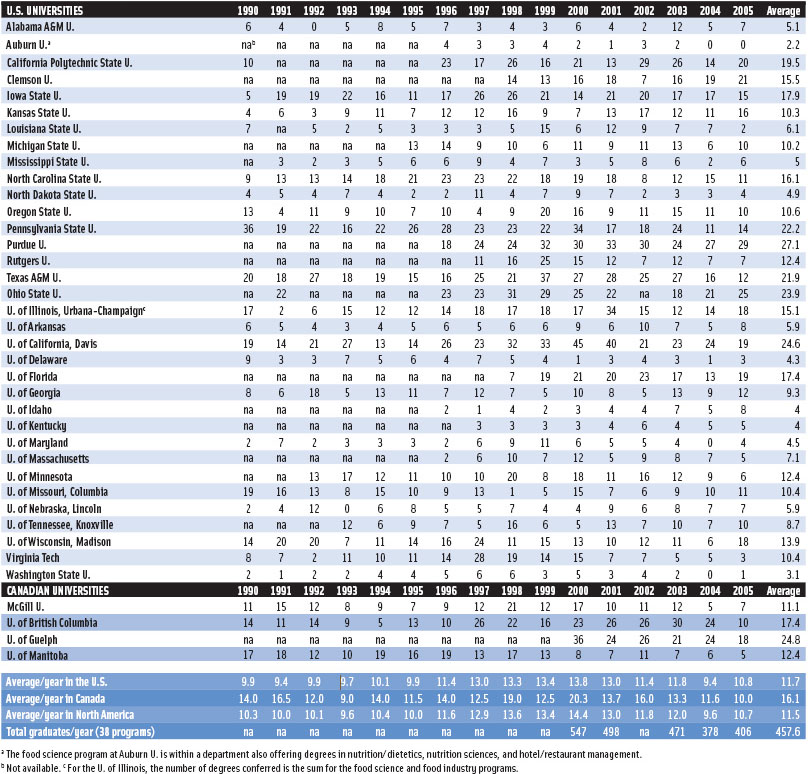

Currently, 47 undergraduate food science programs—41 in the U.S., five in Canada, and one in Mexico—offer curricula and options that the Institute of Food Technologists’ Committee on Higher Education has determined meet the IFT Undergraduate Education Standards for Degrees in Food Science. The standards are listed under “Education” on IFT’s Web site, www.ift.org. We asked these programs for information on the number of Bachelor of Science (B.S.) food science degrees they conferred each calendar year from 1990 to 2005 and received responses from 38 programs. The results are presented in the accompanying table.

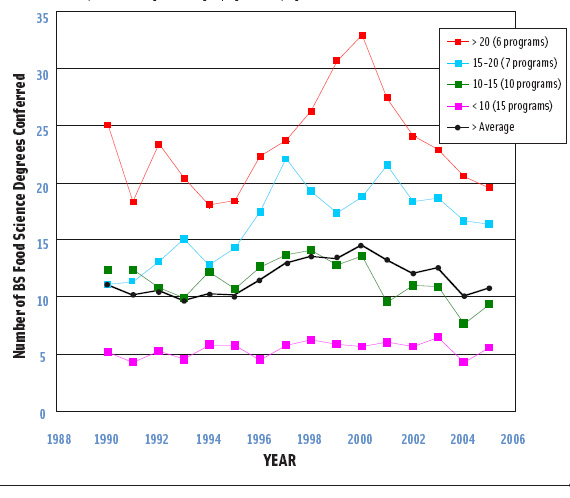

Based on the average yearly number of B.S. food science degrees conferred from 1990 to 2005, the 38 programs were grouped into four categories: (1) >20, (2) 15-20, (3) 10-15, and (4) <10. Under this grouping, six programs conferred more than 20 B.S. degrees; seven programs conferred between 15 and 20 degrees; 10 programs conferred between 10 and 15 degrees, and 15 programs conferred less than 10 degrees.

Purdue University, University of Guelph, University of California-Davis, The Ohio State University, The Pennsylvania State University, and Texas A&M University were the programs conferring more than 20 B.S. degrees, with a yearly average of 27.1, 24.8, 24.6, 23.9, 22.4, and 21.9, respectively.

During 1990-2005, the average number of B.S. degrees conferred by the IFT-approved programs in North America was 12.0. The average number of graduates peaked at 14.4 in 2000, and then decreased to 9.9 in 2004 and 10.7 in 2005. The total number of students graduating with B.S. degrees in food science decreased from 547 in the year 2000 to 378 in 2004 and 406 in 2005. These trends and numbers indicate a decline in the average size of food science undergraduate programs in North America.

The data shown in Figure 1 clearly indicate that in recent years, programs conferring a yearly average of more than 10 B.S. degrees, especially programs conferring more than 20 B.S. degrees, have undergone a decline in the number of degrees they confer. In contrast, programs conferring a yearly average of less than 10 degrees have remained steady in their graduation numbers.

The data shown in Figure 1 clearly indicate that in recent years, programs conferring a yearly average of more than 10 B.S. degrees, especially programs conferring more than 20 B.S. degrees, have undergone a decline in the number of degrees they confer. In contrast, programs conferring a yearly average of less than 10 degrees have remained steady in their graduation numbers.

Factors Influencing the Decline

The global business environment, a strong service-centered economy, and developments in technology have created a strong demand for professionals in a variety of emerging careers, thereby creating new academic fields for undergraduate students to pursue. While overall university enrollments are largely capped, colleges of business, education, health, and communications have witnessed increased enrollments. These changes in higher education may explain the difficulty in attracting students to food science.

For several years, food science programs have put forth concerted efforts to attract undergraduate majors. Department chairs in North America indicated that recruiting students into food science programs remained a challenging task. The low visibility and a poor public understanding of the food science profession was cited as a major reason contributing to the difficulty in attracting students toward undergraduate study in food science.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Most popularly available college-major handbooks, widely used by high-school students while deciding on a major, do not indicate food science as a field of study. In handbooks that do indicate food science, the discipline is inaccurately or inadequately represented. Cooking, culinary arts, and hotel/restaurant management are areas of study that are commonly confused with food science. This lack of public understanding of the food science profession and the lack of a coordinated effort in communicating the field may be other factors contributing to the declining number of B.S. food science degrees conferred by universities in North America.

Most popularly available college-major handbooks, widely used by high-school students while deciding on a major, do not indicate food science as a field of study. In handbooks that do indicate food science, the discipline is inaccurately or inadequately represented. Cooking, culinary arts, and hotel/restaurant management are areas of study that are commonly confused with food science. This lack of public understanding of the food science profession and the lack of a coordinated effort in communicating the field may be other factors contributing to the declining number of B.S. food science degrees conferred by universities in North America.

Support of educational activities and investment in research and development by private and government sources are good indicators of the economic viability of specific industries and professional/career prospects associated with that industry segment. Apart from creating new knowledge, industrial support of higher education creates publicity and brings visibility to the profession, raises awareness of the profession in the civic arena, and attracts talented young minds and the next generation of professionals to the area of study.

While the engineering, chemistry, and other science-based industries have been active in sponsoring research, educational programs, and talent competitions at the high-school and college levels to attract students to their respective fields, the food industry has been relatively passive in supporting food science education or communicating food science to potential students. The research base in the food industry has also declined in recent years, and few food companies remain leaders in R&D. The limited participation of the food industry in food science education and research may contribute to the difficulty in attracting students to food science.

Implications

Membership in IFT has experienced a modest but steady decline in the past dozen or so years. If the number of B.S. degrees conferred and membership in a professional society can be used to assess strength and viability of a profession, then the food science profession is on the wrong path in North America. The continued decline in number of B.S. food science degrees conferred has foreseeable implications that will affect the food industry, the food regulatory environment, and academia.

• Industry. Currently in the U.S., the added value on agricultural products after the farm gate accounts for 80% of the $830-billion annual food expenditure market. Hence, for a nation and its food industry, adding value to food commodities through innovation should be an integral part of the overall strategy to expand the agricultural and food system economy, with improved human health and safety and development of rural communities being the indirect benefits.

The food industry is unique, since it can be classified under the sectors of manufacturing, services, and knowledge for economic growth. While the manufacturing and services sectors are open for global competition, the knowledge sector ensures viability and leadership through innovation and new product and process development. However, the food industry, like many manufacturing industries, has been slow to adapt to the rapidly changing world and is heavily dependent on the manufacturing segment alone for revenue generation.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Success in the knowledge-sector of the food system economy calls for a deeper understanding of the many areas of food and nutrition and translating scientific advances to practical applications. Scientists, engineers, and personnel contributing to the knowledge sector of the food system economy also mainly constitute the membership in IFT. A continued decline in the number of qualified graduates entering the food science profession will (1) negatively affect the food industry’s ability to compete in the global economy, generate revenue through the knowledge sector, and stay at the forefront of advances in science and technology, and (2) reduce the numerical strength of professional organizations associated with the food sciences and their scope in influencing emerging global food policy decisions.

• Government and Regulatory Affairs. The U.S. prides itself with a safe food system. Currently, almost 400 food science professionals (members of IFT) work in federal, state, and local government agencies involved in regulating the food supply. Apart from regulating and inspecting the food supply, they work on research and policy issues of national importance, conduct and participate in program reviews, provide leadership in research funding, and partner with industry, consumers, and academia to identify and tackle emerging issues. The declining numbers of food science graduates may indicate a potential future weakness in our food regulatory system.

• Academia. In most major universities, enrollment of at least 13 students is required to sustain an undergraduate course offering. Under this limitation, it is worthwhile to note that more than 50% of the food science departments in North America graduated ≤ 10 undergraduate students in 2005.

Declining undergraduate enrollment in food science programs has a significant implication for the nature of food science higher education itself. Higher education currently operates under the constraints of capped university enrollments and high tuition costs. Under these constraints, departments of higher education have the added responsibilities to attract talented students into their programs of study. University administrators view strength of undergraduate student enrollment as a major indicator in their decision to support and sustain departments of higher education such as food science. A significant and viable food science undergraduate program contributes to a strong faculty, research, and outreach activities that are strategically aligned with the food system and the food industry, an avenue for graduate students to develop their teaching/mentoring skills, and the departmental ability to identify and adapt to the changing face of how knowledge is delivered.

In the past, low enrollments have led to the closure of food science departments in some universities in North America. A recent example is the phasing-out of the undergraduate food science program at Chapman University. Hence, a small undergraduate presence may put any undergraduate program under the risk of being phased out.

Addressing the Challenges

Addressing the Challenges

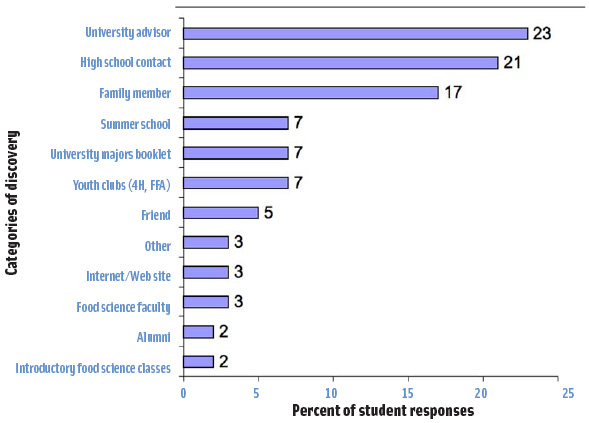

Results of a 2001 survey conducted among 58 food science undergraduate students at Penn State (Figure 2) indicated that 35 students (61%) first learned of food science as an undergraduate field of study through university advisors, high-school teacher/advisor/activity, and family members. The results also indicate that high school teachers committed to food science and an introduction to food science in the high-school curriculum are key to recruiting many of the best students at the high-school level. Consequently, incorporating a food science component in the high-school curriculum, nationwide, is fundamental and in the best interest of all.

Another great audience to communicate the “food science” message to are college students who are undecided on a major field of study or planning a transfer into food science. A 2001 survey of 43 food science undergraduate students at Penn State indicated that 18 students (42%) entered college in another major and then transferred into food science. The top four programs from which students transferred into food science were chemical engineering (3), chemistry (3), animal science (3), and biology (2). The other seven students initially chose agricultural engineering, business, engineering, horticulture, kinesiology, microbiology, or nutrition. Students cited diverse career opportunities, good starting salaries, small class sizes, and internship opportunities in the food industry as valuable talking-points for recruiting college students who are undecided on a major field of study or planning a transfer to a different major.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Conveying the correct message of “What is food science?” to target audiences appears to be a critical need. The following are good target audiences: high-school students, high-school teachers, guidance counselors, parents, roommates/siblings of food science students, undergraduate college students undecided on a major field of study, and undergraduate students in other science and engineering programs looking to switch fields of study.

Most food science departments in North America have embarked on a variety of efforts designed to carry the food science message. These efforts are used to address not only recruitment but also retention of students already enrolled in the major. Depending on the specific case and scenario, some efforts/interventions are more successful than others.

Commonly used recruiting methods include:

• Creating departmental positions to address recruitment.

• Providing options of study within food science.

• Providing departmental support to student clubs, and using the momentum of the club to publicize food science at the college and high-school levels.

• Conducting workshops for high-school science teachers in food science and demonstrating hard-to-understand concepts in science, using food as a tool or resource.

• Encouraging undergraduate students to recruit from their high schools.

• Attending programs and recruitment activities specific to high-school students.

• Sending food science information and brochures to advisors of undecided majors.

• Encouraging food science majors to communicate with students in the science majors, hoping the one-on-one interaction with enthusiastic food science students will attract interested students looking to switch their field of study.

• Purchasing electronic flyers on electronic social sites for college students (e.g., Facebook) that provide a link to the departmental Web sites.

Student retention efforts include:

• Allowing field settings as class time for students to integrate and discover many related food science processes in the hands-on, inquiry-based setting.

• Improving introductory food science teaching, and designing a curriculum that exposes the students to the major at an early level of college education.

• Surveying undergraduate students on their impression of “what students think of food science” and constantly striving to improve curriculum and enhance student learning.

• Providing a nurturing environment to students.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

IFT has also taken a leadership role in communicating food science information to multiple audiences and enhancing the visibility and understanding of the food science profession among diverse audiences. The IFT/IFT Foundation/Discovery Education program of 2006 is one example. It resulted in the development and distribution of free, food-science-themed curriculum resources to classrooms across the country. The program, reaching approximately 18,000 public high schools nationwide, was designed to spark interest in food science and technology among U.S. high-school students. It also represents a model for future programs to gain greater visibility for food science (Heldman, 2006).

The IFT Foundation is a community of individual, group, and corporate donors. It plays a leading role in providing scholarships to attract and retain talented graduate and undergraduate students to food science, food technology, and related curriculums. “A Taste for Science” is an IFT Foundation fundraising campaign to prepare the next generation of food scientists. Funds will be used for IFT programs that stimulate an interest in science among students; develop awareness of the science behind food; attract talented young minds to food science; attract and support members of underrepresented groups; and develop the technical and leadership potential within students and young professionals.

The low visibility and the lack of understanding of food science in the public arena have been major hindrances to attract students to food science. The challenge, declining number of food science professionals, can be addressed by the profession by approaching the immediate future with the mindset to recruit the best young minds interested in science. The goal can be achieved through a personal and organizational commitment to communicate and educate citizens on the role of food scientists within the food system.

Educational programs on food science and advertising/ communicating through the mass media will need the involvement, input, and support from all professionals associated with food science in industry, academia, and government. The food industry can further play a leading role by mentoring the next generation of professionals through expanded internship programs and placement initiatives.

By implementing these programs, we can ensure that the important responsibilities of guiding future food policy and providing safe, affordable, and wholesome food to the growing world population smoothly transition to the next generation of a strong food science profession and a flourishing food industry.

Naveen Chikthimmah, Ph.D. ([email protected]), a Member of IFT, is Instructor of Food Science, and John Floros, Ph.D. ([email protected]), a Professional Member and 2006–07 President-Elect of IFT, is Professor and Head, Dept. of Food Science, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802. Send reprint requests to author Floros.

References

Fletcher, A. 2006. Lack of good graduates crippling food industry. www.foodproductiondaily.com/news/ng.asp?id=66079-food-food-technology-drink. Accessed 2/27/06.

Gilmore, J.L., Goecker, A.D., Smith, E., and Smith, P.G. (authors) and Boteler, FE., Gonzalez, J.A., Mack, T.P., and Whittaker, A.D. (contributors). 2006. Shifts in the production and employment of B.S. degree graduates from U.S. colleges of agriculture and natural resources, 1990-2005. A background paper for a leadership summit to effect change in teaching and learning. Natl. Acad. of Sciences, Washington, D.C., Oct. 3-5, 2006.

Heldman, D. R. 2006. IFT goals and member participation. Food Technology. 60 (9): 11.

IFST. 2006. Research to investigate the U.K. requirement for food scientists and technologists. Summary document. Inst. of Food Science and Technology and Improve-Food and Drink Sector Skills Council, York, UK.

NAS. 2006. Rising above the gathering storm. Energizing and employing America for a brighter economic future. Committee on Prospering in the Global Economy of the 21st Century: An agenda for american science and technology. Natl. Acad. of Sciences, Natl. Acad. of Engineering, Inst. of Medicine, Washington, D.C. www.nationalacademies.org/ocga/testimony/Gathering_Storm_Energizing_and_Employing_America2.asp.