Mission, Myths, and Alt-Meat Momentum

Impossible Foods’ Sue Klapholz dreams of a post-animal food system. To get there, she says we should focus more on evidence-based science, and less on misinformation about processed foods.

Article Content

Sue Klapholz is ready for the revolution. More than ready, really. The Impossible Foods vice president of nutrition, health, and food safety has been working to effect food system change for over a decade. And although her career trajectory has been unexpected, it’s equipped her to handle the demands of her diet- and nutrition-focused role, which includes some serious myth busting about processed foods.

Like her husband, Pat Brown, who founded the groundbreaking alternative meat company in 2011, Klapholz has both MD and PhD degrees. The rigor of her training as a physician and a geneticist, coupled with early professional experience in biotechnology, fortifies her commitment to an evidence-based approach to nutritional analysis.

“We were trained as scientists to be very rigorous thinkers and to be very critical of evidence,” Klapholz reflects. “And I think as MDs we know about the connection between diet and health.

“I think especially in the nutrition area, there’s a lot of misinformation floating around, a lot of mythology,” continues Klapholz, who worked with Brown to help get both Impossible Foods and plant-based yogurt and cheese maker Kite Hill, which Brown co-founded, up and running. “I think it’s very important for us—and this is something we do—to really read the original papers on a topic, form our own conclusions, and then try to explain to the public in a very clear and evidence-based way what the story is.”

Such values—along with Brown’s often-stated mission of addressing climate change via a move away from animal agriculture—are implicit in the corporate DNA of Impossible Foods. Personal, planetary, and public health are intertwined, Klapholz emphasizes.

Friendly and unassuming, Klapholz spoke candidly with Food Technology about what’s ahead for Impossible Foods, why she’s not a fan of the NOVA approach to food classification, and her vision for the food system in 2035.

Q: A vocal segment of the food community, as well as a large portion of the general public, categorizes processed foods as unhealthy, and Impossible Foods has been criticized for its processed products. As a physician and a scientist, how do you respond to that?

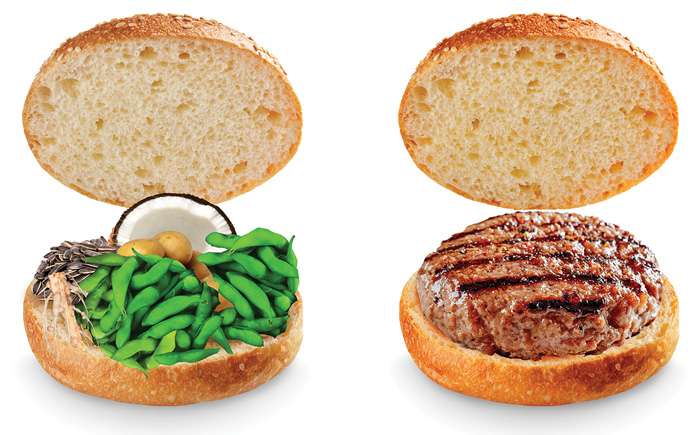

Klapholz: I recently wrote a blog called “Unapologetically Processed” to talk about this because I feel like, yes, we are a processed food and proud of it. We would never achieve our mission if we took whole soybeans, chunks of coconut fat, whole root nodules—all the key ingredients that we use in our product—and just threw them together on a bun. It’s essential that we use processed ingredients to create the replica of an animal product that really has all the authentic sensory properties.

Q: There are those who maintain that we should all stick to natural, whole foods. What do you say to them?

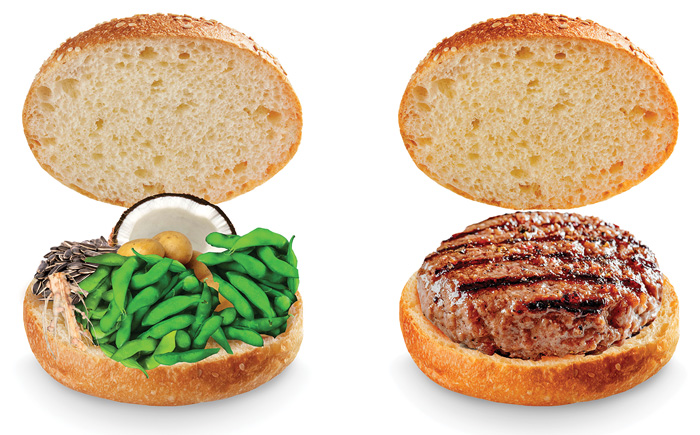

Klapholz: I think when people say, “Oh, you should have a green salad and lentils and rice,” we're not saying don't eat your green salad and don't eat your lentils and rice; that's very important. I think balanced whole foods are key to a healthy diet. But instead of choosing a hamburger from a cow, choose the Impossible Burger. Instead of choosing a sausage patty from a pig, choose Impossible Sausage. Or instead of chicken nuggets, now choose our chicken nuggets. I think that we provide alternatives that are comparable, if not better, in nutrition.

Q: The high-profile NOVA system classifies the Impossible Burger as “ultra-processed.” What are your thoughts about this approach to evaluating nutritional quality?

Klapholz:I’m very critical of the NOVA classification. I think that it’s overly simple. I would say that there’s junk food and there’s highly nutritious processed food like soymilk. They are apples and oranges. They have almost nothing in common.

The NOVA food classification system implies that there is a direct correlation between the degree of processing and the healthiness of a food, but this is an overly simplistic and scientifically unfounded conflation. Processing does not, by definition, make a food or an ingredient less healthy.

In fact, there are countless examples to the contrary, where processing has enhanced food safety or improved its nutritional profile. Processing is used to inactivate harmful phytochemicals (for example, lectins in kidney beans) and kill foodborne pathogens.

Potato protein, an ingredient in the Impossible Burger, used to simply be a waste product of the potato starch industry. Potatoes are mainly composed of water and starch, with protein constituting only 2% of their makeup. By isolating and concentrating the protein from potatoes, we get a high-quality protein, free from starch, that can be used as a nutrient-dense food ingredient.

Putting a deep-fried doughnut and a nutrient-packed plant-based burger in the same NOVA category just does not make sense from a nutrition and health perspective.

Q: Do you see the potential for Impossible Foods’ products to address specific public health concerns?

Klapholz: We think about how in certain parts of the world people have nutritional deficiencies that we might be able to meet by adding additional nutrition to our products. [In] an area where people are deficient in vitamin A, we could potentially include vitamin A in an animal replacement even if the animal itself didn't have vitamin A. … This is future thinking on our part—that we would like to do this sort of thing. We haven’t done it yet.

Q: Going back to the origins of Impossible Foods, did you share Pat Brown’s vision of reducing the impact of animal agriculture on the planet by advancing plant-based food consumption?

Klapholz: It really came from Pat. He was a professor at Stanford, I think, in total, about 25 years. And he loved what he was doing. And every seven years or so he was able to take a sabbatical. So one year he decided he would take a sabbatical at home, and he would try to work on what he thought was one of the most important problems facing the world, and that was global warming. And through his reading and investigation, he made the connection between climate change [and] loss of species diversity to animal agriculture. He made that connection, and I learned from him about that.

Q: One of the things that sets Impossible products apart is the meaty flavor that comes from the iron-containing molecule heme. Would you share the story of how Pat figured out how to derive it from a plant-based source?

Klapholz: During his sabbatical year, our kitchen was his lab essentially. We live on the Stanford campus in a townhouse, and there’s a little hill behind where we live, and he would go and pick clovers, which are legumes, and he would sit at the kitchen table with little tweezers and dissect the root nodules and eventually he was able to find greater sources of root nodules to dissect and isolate leghemoglobin from.

Q: And the rest is Impossible Foods history! Is it fair to say that both of your career trajectories have taken you in unexpected directions?

Klapholz: Mine was all over the place because I worked in a biotech company, a startup company, and then I was essentially a stay-at-home mom who did a lot of consulting, scientific editing, creative writing—all kinds of things. But I had not gone back into the lab for quite a while.

Q: How did you get started with the company?

Klapholz: Early on in the company I just was kind of a volunteer. I ordered our company’s first centrifuge. And I was asked to help with the cheese project.

And so I did that part-time. I would sit at the front desk, actually, in our small first office, and I would also greet people, and then I would go and work with the cheese team. And this became a bigger and bigger job until it became full-time.

Q: So you worked for both Kite Hill and Impossible Foods?

Klapholz: In the beginning, we had two new companies working in one space, the company that is now Lyrical Foods (Kite Hill brand) and what is now Impossible Foods. The two companies shared office and lab space for about one year. I worked with a small team on the original artisanal Kite Hill cheeses. After Kite Hill moved to its own location in Hayward, Calif., I led a cheese team at Impossible Foods for another three-to-four years. That project was temporarily put on hold when we got close to launching our first product, the Impossible Burger. I then started the Nutrition and Health team at Impossible.

Q: Tell us about how health and nutrition fits into the product development process at Impossible Foods.

Klapholz: We’re involved from the very beginning. We look at the animal product that we’re replacing, and we look to see what nutritional positives, neutrals, [and] negatives are there. And how can we replicate or improve upon everything that’s good [and] minimize or eliminate everything that’s a health negative—and include or add additional nutrition or health benefits?

Q: How does the process start?

Klapholz: Usually they'll start with a prototype, and that will be built upon until we have what we consider a final product. And in that development process, nutrition is constantly changing, ingredients are changing, levels are changing. We're trying to balance all the organoleptic properties of the product with the nutrition, with the cost, with the manufacturing process and with handling properties, shelf-life properties—all that. So we're part of that team, and we help guide the process along by testing the product at various time points, and I also created a nutrition calculator.

Q: How does that work?

Klapholz: We use that to calculate how we’re doing in terms of creating our final product. So we can give the team an idea: “Okay, you have 18% protein now. If your target is 20%, let's think about ways to up the protein amount.” We calculate the PDCAAS (protein digestibility amino acid score), and we keep our eye on that. So we're making sure that our quality is high. It's not just the amount of protein but that our protein quality is excellent as well. And it's easy to do that with soy, but sometimes we have a complex mixture and it's not as simple.

Q: And your team has a food safety role as well, right?

Klapholz: Every time we get new ingredients into the company, my team evaluates them for safety as well as nutritional attributes. So we look at heavy metal levels in all ingredients. We look for contaminants. Certain ingredients we'll test for pesticides and mycotoxins. We're very focused on safety as well as nutrition and health.

Q: Let’s talk about another topic that you have strong feelings about—the relationship between animal agriculture and human health. Why is that so important?

Klapholz: As an MD, I've been very aware of the link between the way we raise animals and a lot of public health issues—for example, influenza epidemics and pandemics originating in farmed chickens and pigs. And the other is multiple antibiotic resistant bacteria that arise from feeding farmed animals antibiotics throughout their lifetime. And so some of these problems, which I think are real public health problems and that I'm quite aware of as an MD, really, to me, that's another very important aspect of our mission.

Q: I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask about the role that food scientists play at Impossible Foods, as well as the role of scientists from other disciplines.

Klapholz: I think that differences in perspective, training, and expertise—mixing people with these differences—really expands our ability to think outside the box and do groundbreaking research.

We do have some wonderful food science veterans at our company. And their industry knowledge is invaluable. I think it's also good to have people who come in fresh out of academia with no idea of how things are done in the food industry, bringing fresh ideas that might help us to innovate. I think it’s good to have a combination of industry knowledge.

Maybe a physicist or a mechanical engineer would bring some great ingenuity to how do you create a structure that's different from ground beef, that has a structure that is consistent with a whole cut of steak or fish or chicken.

Q: You mentioned whole-muscle meat cuts. Is that on the product development agenda?

Klapholz: Absolutely. It's something we're exploring. We are working on whole cuts of all kinds, including steak, chicken, and fish. We are pretty good now at figuring out how to create really good flavor. I think that for whole cuts, the challenge is very structural. Getting the texture, the appearance, even how it feels when you're cutting it, the mouthfeel—those are the challenges there. We're working on that now.

Q: What do you anticipate the future of Impossible Foods will be? There has been some talk about an initial public offering (IPO) or a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC).

Klapholz: We haven't announced any plans for an IPO or SPAC. I know that's been thrown around. Right now, we're still just really laser focused on expanding our product lineup and availability of our products globally. So that's really where our focus is. For future direction, I would love to see us realize our mission. I would love to see us—and whatever other companies join in—make this happen. I would love to see climate change stopped or reversed.

Q: You’ve stated that your goal is to live a balanced life that’s joyful. How would you say that your work at Impossible Foods contributes to that?

Klapholz: Well, first of all, I love working at Impossible. The vibe in the office—it’s an open office where nobody has a closed door—is just wonderful and very conducive to interaction and establishing friendships and connections and being able to easily get information from anybody by walking over to where they're sitting. So the environment there is very good as far as I have an amazing team, and I really enjoy mentoring them. But we also have a bunch of employee resource groups (ERGs) at Impossible. These ERGs have different focuses, and I'm a member of almost all of them, I think, and being a part of those is also very important to me.

Q: Would you share a bit about how you and your family eat?

Klapholz: Pat and I were both vegetarian when we met in grad school. So Pat and I were vegetarians for many, many years, and about 18 years ago we became vegan.

It was actually when I turned 50. I decided that I knew enough about all the ways animals were raised in agriculture that it wouldn’t be consistent with my personal beliefs to consume eggs or dairy any longer. And that was harder than becoming vegetarian because giving up cheese was super hard. But I did it. And Pat immediately joined me.

Our children were raised vegetarian, and they all are either still vegetarian or vegan at this point in life. They never considered anything else. And I think both Pat and I were very much motivated by our feelings for animals and not really seeing a distinction between the animals we call pets and the animals we call food.

Q: Some analysts say that it’s going to take from five to 20 years for products like the ones Impossible Foods is making to reach price parity with animal products. Will alternative products always be premium-priced compared with conventional meat products?

Klapholz: No, I don't think they'll always remain more premium. We've been working very hard over the years to continue to reduce our price. We have had three double-digit price cuts in the last one-and-a- half years—two 15% reductions for restaurant distributors and one 20% cut on our retail prices. So we're providing lower prices to restaurants and grocery stores and we're able to do this because there is an increasing demand and because we're scaling up production.

So economy of scale is really, I think, the key for us. And I think the economics will change as plant- based products fill the market and animal products maybe become themselves more expensive to produce. Then that may affect the equation as well.

Q: Before we wrap up, let’s talk more about the future of the food system.

Klapholz: We're really envisioning a plant-based world, right? We're not just thinking, "Okay, we're going to make some food, and this is how it is now." We're thinking [that in] 2035, if we achieve our mission and there's no more animal agriculture and we're a predominantly plant-based world, we want people to be healthy and well nourished. We ultimately want to create food that is good for the planet and its people: sustainable, healthy, nutritious, and affordable.

Q: Is it possible for the food system to change that much in less than 15 years? And what role will you and Impossible Foods have played in effecting that change?

Klapholz: I hope I will be here to see that in 2035. But that's our target. It could be sooner. It's an ambitious goal, but it keeps us very motivated and very focused. I feel great about the fact that we've been a part of what I feel like is a food revolution.

I'm very excited about all the other big food companies that have gotten involved and have come out with plant-based burgers and other meat alternatives. All of this shows me that we're heading in a really positive direction, that people are accepting these plant-based foods. They want them [and] they're buying them.

This interview was edited for clarity and brevity.

Vital Statistics

Credentials: B.S., Biology, Cornell University; PhD, Genetics, University of Chicago; MD, University of Illinois

Specialties: Nutrition, Genetics, Psychiatry

Meaningful Pursuits: Mentoring two women at Impossible Foods

Outside Interests: Family, friends, nature photography, jewelry design, and serving as president of the Palo Alto Humane Society Board of Directors

LinkedIn: Sue Klapholz