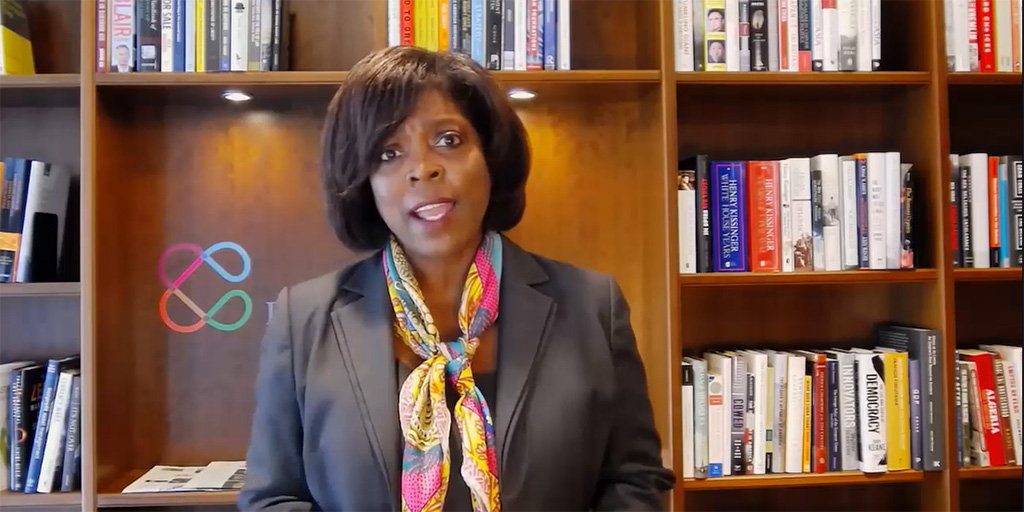

Keynoter Ertharin Cousin Offers Stark, Yet Hopeful, Assessment of Zero Hunger Hurdles

FIRST News

To naysayers who doubt that zero hunger goals are realistic and achievable, Ertharin Cousin counters with a simple, direct question: If China can do it, why can’t everyone?

In her kickoff keynote address Monday to FIRST, the former U.S. ambassador to the UN Agencies for Food and Agriculture, and later executive director of the World Food Programme recounted how China suffered a series of famines in the late 1950s, resulting in nearly 50 million deaths. “But things changed in China,” she said. “Despite the fact that some 60 years ago, the world said China would never be able to feed itself, not only does it feed itself today, but it is also a donor country, supporting food access across the globe for developing countries.”

“So, if they can do it in China, why can't we end hunger?” she continued. “Why can't we achieve zero hunger across the world?”

Still, Cousin offers a stark assessment of a broken global food system, in which 690 million people lack the food, water, or other resources necessary to sustain themselves. “Indeed, 3 billion people can't afford a healthy meal,” she said. “They fill their stomachs too often with empty calories, because that's all they can afford; and 250 million people are acutely hungry, living on the verge of starvation. Too often, conflict and climate are affecting 250 million people, and we say they're acutely hungry because too often they die from lack of access to food.”

Cousin added that almost 40% of all the food cultivated is wasted, a loss of $680 billion.

The COVID-19 pandemic only exacerbated this problem, as lockdowns and other restrictions resulted in huge food waste. “Drivers, who normally would drive produce in the evenings when it's cooler, because of curfews, they couldn't drive in the evenings anymore, so they drove during the day, in trucks that were not refrigerated, and put food in warehouses that were not refrigerated, and as a result, what did we see? Increases in food loss, and increases in food prices, making food even more unaffordable for the working poor and low-income families,” she said.

But Cousin adds that the pandemic also might have provided a much-needed wake-up call. “What COVID did was made the world pay attention to food systems,” she said. “Food systems suddenly became a topic of conversation not just with people like me and you, who spend our lives addressing issues related to food, but with the entire global community. We suddenly began to wonder, could we do better?”

What will it take to achieve this? Cousin cited three key hurdles to overcome:

- Commitment to research and innovation: “Science gives us more tools to do better at every level,” Cousin said. “At the farm level, providing new seeds that provide for greater yields with less water and less land, and less need for creating increased biodiversity, and reducing the amount of food that is consumed; reducing the amount of water that is consumed at farm level for the production of food. So agtech, biotech, that supports advanced plant breeding, that provides for new tools at the farm level.

“But even at your level,” she continued, “having food tech provides us with food that is more shelf-stable, that is more nutritious, that has less sugar, more calories, and still tastes good, because we need to ensure that consumers want healthier food because the food tastes good.” - Coordinated cooperation: “No one sector is going to make the changes that are necessary to improve the global food system for all, “she said. “So, we need the collective action across the food chain, from farmers to consumers, to change their behavior, to change what we produce, to change in a way that will ensure we create a food system that provides for healthier food for the body, as well as for the environment, as well as the economic return for all stakeholders across the food system, from farmers to manufacturers, to the investors in our food system.”

- Food as health: “About 2.8% of global GDP is directly related to the health consequences of diet-related disease,” Cousin said. “So, how's the world responding to that? We're beginning this dialogue across the globe about food as medicine, providing food prescriptions to allow for those who become ill with a food-related disease to have access to affordable, nutritious food.

“How about we change it, provide affordable, nutritious food before people become ill, reduce the costs, the $690 billion cost of diabetes every year around the globe, by ensuring that people have the access to the food that will prevent diabetes? So, embracing food as health, not just food as medicine.”

Cousin closed with a personal anecdote from her time as executive director of the World Food Programme. “I refused to take pictures with babies suffering from famine, undernourished children,” she recounted. “I wanted us to send a different message to the world of what was possible, so every place that I went, we took pictures with the fattest, healthiest, happiest babies we could find, because we wanted the world to see when we did the right thing, the outcome, no matter how tough the context, we could make it different.

“We can do this,” she said.

Digital Exclusives

10 Food Trend Predictions for 2022

The editors at Food Technology magazine, published by the Institute of Food Technologists (IFT), have announced their predictions for the hottest food trends for 2022.

Food Technology Articles

How to Achieve EPR-Forward Packaging

In this two-part series, the author explores the history of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), what is needed to help EPR succeed, and how brands can best prepare for EPR.

Production Capacity Expands for Food to Fight Malnutrition

Production capacity for ready-to-use therapeutic food Plumpy’Nut at Edesia expands thanks to a Bezos family donation.

Keeping the ESG Promise

An infographic describing food and beverage companies’ outlooks regarding ESG initiatives.

Ag-Tech’s Passionate Pragmatist

Agrologist and agricultural futurist Robert Saik wants to feed the world better and more sustainably. To make that happen, leveraging science and technology will be critical.

USDA Introduces Summer Benefits for Children Pear Preferences and Cultivated Meat Research

Innovations, research, and insights in food science, product development, and consumer trends.

Recent Brain Food

A New Day at the FDA

IFT weighs in on the agency’s future in the wake of the Reagan-Udall Report and FDA Commissioner Califf’s response.

Members Say IFT Offers Everything You Need to Prepare for an Uncertain Future

Learn how IFT boosts connections, efficiencies, and inspiration for its members.

More on the FDA's Food Traceability Final Rule

In a new white paper, our experts examine the FDA’s Food Traceability Final Rule implications—and its novel concepts first proposed by IFT.

Job Satisfaction in the Science of Food is High but Hindered by Pain Points

IFT’s 2022 Compensation and Career Path Report breaks it down.