When Science Follows Technology

Dialogue

December 2021/January 2022

Volume 75, No. 11

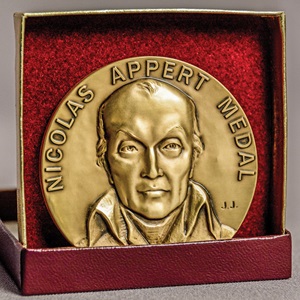

IFT’s highest award is the Appert medal, first given by the Chicago Section in 1942. Writing in this magazine in 1952, Milton Parker suggested the impetus for the award came from Avrill Bitting, who, along with his wife, Katherine, was deeply involved in the development of the canning industry in early twentieth century America. While canning is commonplace today, for that generation of food technologists it was a paradigmatic example of the power of science to change food for the better. Canned food existed when they were young, but it was expensive and unreliable; by the mid-twentieth century it was affordable and safe. Nicolas Appert invented canning and so was an ideal hero.

IFT’s highest award is the Appert medal, first given by the Chicago Section in 1942. Writing in this magazine in 1952, Milton Parker suggested the impetus for the award came from Avrill Bitting, who, along with his wife, Katherine, was deeply involved in the development of the canning industry in early twentieth century America. While canning is commonplace today, for that generation of food technologists it was a paradigmatic example of the power of science to change food for the better. Canned food existed when they were young, but it was expensive and unreliable; by the mid-twentieth century it was affordable and safe. Nicolas Appert invented canning and so was an ideal hero.

The second award of the Appert medal was to the founding president of IFT, Sam Prescott, dean of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Prescott’s first major achievement in food science occurred in 1895, when William Lyman Underwood asked his help in addressing spoilage issues in his family’s canned food business. Prescott worked with Underwood to adapt new methods of environmental microbiology to identify the organisms responsible for the swelling and souring of canned peas and clams and published his results. He went on to teach the first courses in food technology at MIT and eventually founded the first food science department.

While it makes perfect sense that the Chicago Section chose Appert’s name to exemplify excellence in food science, Appert himself was no scientist. He worked as a brewer and a chef before setting up a confectionery store in Paris, where he was caught up in revolutionary politics. He served as an officer in the militia and even assisted in the execution of King Louis XVI before being arrested; he was only released when the revolutionary government fell in 1794. He went back into business, working on a plan to preserve food in glass bottles and by about 1795 hit on the process he described later: “first, to enclose in the bottle or jar the substances that one wishes to preserve; second, to cork these different vessels with the greatest care because success depends chiefly on the closing; third, to submit these substances thus enclosed to the action of boiling water in a water-bath for more or less time according to their nature and in the manner that I shall indicate for each kind of food; fourth, to remove the bottles from the water-bath at the time prescribed.” (Appert published his methods in 1810 as The Book for All Households, which Katherine Bitting translated into English.)

Appert invented canning without relying on established scientific theory. He was an entrepreneur and an obsessive “tinkerer” over decades. His measure of success was not scientific but practical and economic.

Appert invented canning without relying on established scientific theory. He was an entrepreneur and an obsessive “tinkerer” over decades. His measure of success was not scientific but practical and economic.

Although Appert was not successful in business (his workshop was damaged by foreign soldiers after the fall of Napoleon), his ideas spread rapidly—first to England and then to America and the rest of the world, where people adapted them to local conditions. We can identify some of the major inventions that improved canning through the nineteenth century and beyond (metal cans, the can opener, the pressure retort, the double seam), but there are countless “micro-inventions” by unknown food technologists looking at a process, imagining a better way to do it, and then making their idea work in practice. These large and small improvements allowed the success of many canning businesses by the time Underwood walked into Prescott’s office at MIT. Indeed, only an established industry could expect to attract the attention of the scientists. The canners already knew how to process foods, but Prescott and his scientific peers developed systematic explanations of why it worked, and by sharing that knowledge in publications and in classes, they built a generally agreed upon understanding. This was important, but the science didn’t lead to the technology—the technology led to the science.

The growing list of Appert medalists provides an inspiring story of how scientific excellence has continued to improve food processing over the past 79 years, but the example of Appert’s life should also make us think of the power of tinkering. What can we do better to develop and recognize these practical and essential skills?

In reality, Nicolas Appert was much more a "tinkerer" than a scientist, which isn't a bad thing. Do you know of any examples of this sort of small "ground level" inventions? IFT members can share their examples and thoughts on the topic in IFT Connect.

Food Technology Articles

How to Achieve EPR-Forward Packaging

In this two-part series, the author explores the history of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), what is needed to help EPR succeed, and how brands can best prepare for EPR.

Battling Biofilms

In this column, the author describes the stages of biofilm development in food processing plants, methods of removal, and best practices for prevention.

Smart Steps to Peak Traceability

Creating an effective road map to advance your food traceability program is key to overcoming data, process, and stakeholder challenges.

Ensuring Quality and Safety in Fried Foods

In this column, the author describes basic principles for maintaining frying oil quality and safety.

Best Practices for Chemical Hazards

This column offers expert tips on best practices to help mitigate food chemical hazard risks that have made recent headlines, including PFAS, BVO, and heavy metals.

Recent Brain Food

A New Day at the FDA

IFT weighs in on the agency’s future in the wake of the Reagan-Udall Report and FDA Commissioner Califf’s response.

Members Say IFT Offers Everything You Need to Prepare for an Uncertain Future

Learn how IFT boosts connections, efficiencies, and inspiration for its members.

More on the FDA's Food Traceability Final Rule

In a new white paper, our experts examine the FDA’s Food Traceability Final Rule implications—and its novel concepts first proposed by IFT.

Job Satisfaction in the Science of Food is High but Hindered by Pain Points

IFT’s 2022 Compensation and Career Path Report breaks it down.