Improving Hospital Foodservice

Hotel-style services and haute cuisine improve patient satisfaction in hospitals.

Imagine ordering pecan-crusted trout, quinoa, and asparagus spears with lime from your hospital bed and receiving the order by a tuxedo-clad waiter who delivers your meal on request. This scenario is not the hospital of the future, but rather one of several customer-centric services being offered at a growing number of healthcare institutions in an effort to improve patient satisfaction.

Research findings indicate that foodservice quality is significantly correlated with overall patient satisfaction. (Sheehan-Smith, 2006) Therefore, it is not surprising that hospitals are responding to the challenge by implementing customer-centric services, such as room service, spoken menus, pod systems, and more. Eating is not only a significant element of comfort for patients during their hospital stay but also a vital necessity. Inadequate food intake during a hospital stay worsens the prevalence and degree of malnutrition associated with increased morbidity, length of stay, and mortality. The total impact of hospital malnutrition on social and healthcare cost is considerable and mostly underestimated. Therefore, optimized feeding of hospitalized patients is part of the strategy to improve clinical outcomes.

Research findings indicate that foodservice quality is significantly correlated with overall patient satisfaction. (Sheehan-Smith, 2006) Therefore, it is not surprising that hospitals are responding to the challenge by implementing customer-centric services, such as room service, spoken menus, pod systems, and more. Eating is not only a significant element of comfort for patients during their hospital stay but also a vital necessity. Inadequate food intake during a hospital stay worsens the prevalence and degree of malnutrition associated with increased morbidity, length of stay, and mortality. The total impact of hospital malnutrition on social and healthcare cost is considerable and mostly underestimated. Therefore, optimized feeding of hospitalized patients is part of the strategy to improve clinical outcomes.

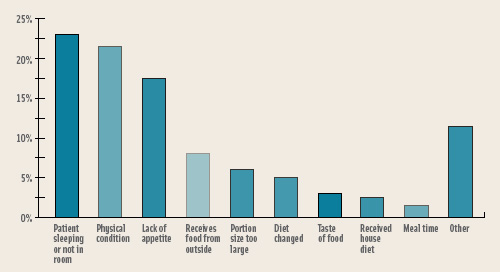

Several studies conducted in the past few years have concluded that, despite sufficient food provision, most hospitalized patients did not consume enough calories to meet their estimated nutritional needs (Dupertuis et al., 2003). A plate waste study at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in 1998 revealed that a large percentage of our patients were consuming less than half of the food on their trays. Subsequent studies indicated that poor meal consumption had very little to do with the food but, surprisingly, correlated with the patients’ missing a meal because they were either sleeping or not in their room when the meal was served. A late tray could have been requested, but many patients did not bother to request one (McLymont et al., 2003).

Several studies conducted in the past few years have concluded that, despite sufficient food provision, most hospitalized patients did not consume enough calories to meet their estimated nutritional needs (Dupertuis et al., 2003). A plate waste study at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in 1998 revealed that a large percentage of our patients were consuming less than half of the food on their trays. Subsequent studies indicated that poor meal consumption had very little to do with the food but, surprisingly, correlated with the patients’ missing a meal because they were either sleeping or not in their room when the meal was served. A late tray could have been requested, but many patients did not bother to request one (McLymont et al., 2003).

Room Service

Improving patients’ perception of hospital foodservice and ultimately their satisfaction requires improvements in the delivery system, the menu, the staff, and the level of service provided. At MSKCC, we have developed a “3E” approach to quality improvement: exceptional service, enhanced nutrition care, and excellent food.

Our approach to improve service is our Room Service program, which allows patients to eat the food they want when they want it. All of our patients except those who are tube-fed or receiving total parental nutrition receive a personalized menu, designed like a restaurant menu, listing only the foods they are allowed to eat. When patients are ready to eat, they can indicate their food selections verbally by contacting the call center (diet office) or telling their Room Service Associate, a foodservice employee assigned to each patient unit of 35–50 patients. This Room Service Associate distributes menus, explains the foodservice program, takes patient food selections, delivers patient meals, tracks missed meals, collects dirty trays, etc. The Room Service Associate prepares the patient for the meal service by helping clear the bedside table and adjusting it to the appropriate height for dining. Then he or she, dressed in a waiter-style uniform, adds hot and/or cold beverages, condiments, etc. from a pantry located on the patient unit. When the tray is delivered, the Room Service Associate helps the patient open the silverware packet, milk or juice carton, or whatever is necessary to prepare the patient to eat (Keffe, 2005; Lang, 2004; Lawn, 2003).

The success of room service is contingent on the timeliness in which the patients receive their order after the initial call. We guarantee service within 40 minutes, but up to 60 minutes is considered acceptable. The equipment utilized as well as the menu are critical components in meeting this service guarantee. We primarily purchase fresh poultry, meat, fruits, and vegetables and utilize these ingredients to create quick recipes that can be produced within 15 minutes. A Waldorf Suite was installed at MSKCC, which currently provides all the firepower needed to produce more than 2,000 meals a day with a maximum of three chefs at any given meal period. The Waldorf Suite includes the following equipment: two grill tops, broiler, salamander, fryer, six step-up burners, pasta cooker, oven, and refrigerated compartments for food storage.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

A computerized system tracks which patients did not order a meal. The Room Service Associate will contact patients who do not order a meal during a given time period to ascertain why they did not order. All patients except diabetic patients are allowed to miss one meal before the foodservice staff intervenes (Lawn, 2003). Rick Wade, Senior Vice President of the American Hospital Association, estimated that 40% of the nearly 4,800 hospitals in the group had changed or planned to change exclusively to a room service–style food program in five years (Severson, 2006) The National Society of Healthcare Foodservice Management (HFM) reported in 2004 that more than 17% of its 2,000 members already have room service and another 50% hope to implement this service in the next 1–2 years.

Room service has many other advantages, including added food choices, decreased plate waste, patient empowerment, improved food quality, and reduced or eliminated nursing staff responsibility for meal delivery. One disadvantage noted is an increase in labor cost because in many hospitals nurses are responsible for delivering the tray (Sheehan-Smith, 2006).

Alternatives to Room Service

When room service is not an option, other effective customer-centric meal delivery programs can be employed to increase patient satisfaction. The spoken menu and cart delivery system has been successful in many healthcare facilities (Jatho et al., 1998).

In this system, foodservice staff visits the patient 1–2 hours before a meal service to assist patients with menu selections. Most foodservice departments use a pre-select menu, which offers 2–3 hot and cold selections. Trays are assembled on a traditional tray line and delivered to the patients’ bedside at the designated mealtime.

Two important features of this system have aided in its success: The spoken menu eliminates wasted trays, because orders are taken in real time, as opposed to the conventional system where orders are taken 24 hours in advance, and it allows for face-to-face contact with the patient, which has been shown to improve tray accuracy and patient satisfaction (Caithamer, 2004). The major difference between the spoken menu and room service is that the spoken menu has fewer food choices and the meal is served at a designated time.

The pod system is another approach to increasing patient satisfaction. Its key feature is the layout and design of three different serving areas or “pods” set up as independent stations in different parts of the kitchen. These serving areas function as tray-loading stations. Two staff members at each station are responsible for assembling meals for six carts at a time, with one employee loading everything except the hot food on each tray. Hot food is loaded by the staff member who serves the tray on the patient unit. Again, the spoken menu concept is used to ascertain the patients’ meal selection. Delivery of the tray by the individual who created the tray is an enhancement to the traditional host/hostess programs seen in many healthcare foodservice settings.

The pod system has shortened assembly time and improved accuracy. Equally as important is the noted improvement in tray appearance and more accountability for each tray because the individual who prepared the tray serves the tray (Anonymous, 2006).

Even small changes can have a significant impact in improving patient satisfaction. Some simple ideas include restyling foodservice employee uniforms to include a food tie or a tuxedo-style apron, replacing plastic with china, offering a mid-day or evening teacart and snack, and adding a small vase of flowers to the tray (Caithamer, 2004).

Haute Cuisine

Recruiting a culinary-trained chef is key to changing the face of healthcare foodservice. As a result, a large number of hospitals are hiring culinary school graduates to run kitchens that are being retooled to let patients order food as if they were staying at a hotel. Baby Boomers, with their well-traveled, restaurant-honed palates, are driving the trend—they spend more time in hospitals as they age, and they want to eat well while there (Severson, 2006).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

HFM has launched an annual Culinary Competition for foodservice directors and their chefs to showcase innovations in healthcare foodservice. At MSKCC, we launched an externship program with the Culinary Institute of America to educate young culinarians about the importance of healthful, well-prepared foods to patient outcome in a hospital. While many trained chefs may chose a hospital setting for the steady hours and benefit package, the opportunity to create in this environment is not only challenging but also rewarding. Healthcare chefs are challenged to create a menu that includes dietary restrictions, is aligned with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and incorporates the latest food trends and flavors.

Most hospital menus are designed to accommodate a multitude of diet restrictions, e.g., reduced salt, fat, and sugar. The foodservice department at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) and Shadyside Hospital in Pennsylvania, implemented a new approach—a liberalized menu, described as a general menu that reflects the “real world” food environment the patient will encounter after being discharged. The menu choices range from” healthy” options like tuna salad on whole wheat and frozen yogurt to everyday selections like lasagna and cheesecake. Early reviews of this program indicate that patient satisfaction improved and plate waste decreased. The positive aspect of this program is that the liberalized diet empowers patients to make their own decisions about menu selection following diet counseling by the dietitian. At first, mistakes will bring increased nutrition counseling; however, if they persist, the patient can be labeled noncompliant. Only one-third of the patients at UPMC and Shadyside are considered candidates for this new approach because some patients are in intensive care, are tube-fed, or have clinical (gastric bypass, renal) or cultural (kosher, etc.) restrictions (Buzalka, 2006).

Modified diets are not going away in a healthcare environment, but patients receiving a modified diet should have more choices. About one-third of respondents to an HFM member survey said they were using a broader restaurant-style menu instead of a conventional or a pre-select menu that offers 2–3 hot and/or cold choices). A restaurant-style menu can offer a range of hot and cold entrees, sandwiches, grill items, and more. Increased food choices have been shown to correlate directly with increased patient satisfaction. In addition to our restaurant-style room service menu (with more than 25 food choices), we offer a daily soup and entrée special, as well as the cafeteria menus for patients with longer stays (Lang, 2004; Lawn, 2003).

The 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans emphasize the inclusion of more whole grains, fresh fruits, and vegetables and less fat (especially trans fatty acid) in the diet. Hospital chefs are creating such offerings as bulgur wheat salad with berries, quinoa with roasted chicken, and multigrain pancakes. Also popping up on menus are fruit smoothies, fruit parfaits, and cut apples with caramel dipping sauce. We can thank fast-food chains for marketing fresh fruit, especially to the younger population. Equally as important for hospital foodservice is assuring patients that foods are prepared with oils that are low in saturated fat with zero trans fats.

Food preparation methods vary from hospital to hospital depending on budget, equipment, and experience of staff. When possible, many operators would like to utilize fresh meats, poultry, fish, fruits, and vegetables. However, cook-chilled foods and frozen products are highly utilized for menu variety and consistency in quality for multistep recipes or ethnic foods. HFM reported that more than 25% of its members have a cook-chill facility. Most popular frozen products utilized in many institutions are soups, vegetable, sauces, and such popular items as lasagna, chicken fingers, and French fries.

Hospital menus are used as marketing tools as well as educational tools for patients. A successful team consisting of the clinical dietitian and the chef can create this balance to the benefit of the patient choices.

Food Trends

The biggest challenge for healthcare foodservice chefs is to keep pace with food trends and incorporate these foods on the hospital menu when possible. To combat menu monotony for patients, chefs have to continually experiment with new flavor profiles and create a new slant to traditional comfort foods. Whole grains, organics, bottled water, ethnic flavors, and functional foods are among the top food trends.

Some healthcare institutions are also going green. Organic trend trackers reported that healthcare foodservice departments purchased organic fruits and vegetables, hormone-free milk, mixed greens, deli meats, and salad dressings most often last year.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Bottled water has been correlated with a healthy lifestyle, and it is not surprising that patients are requesting bottled water instead of the traditional pitcher of water at the bedside. Even vitamin water is being offered on the clear-liquid menu at hospitals.

Appearing on today’s healthcare menus are emerging tastes such as miso, tandoori, and cumin, while mainstream flavors such as ginger, curry, thai, cilantro, and peanut are still favorite additions to any menu. A menu incorporating platform foods, such as a chicken breast, can be transformed into curry, tandoori, or even a thai chicken dish. Adding different flavor profiles provides the much-needed variety without the cost. Other innovations include the introduction of lemongrass and miso broth to traditional liquid menus.

With regard to functional foods, hospital menus are offering fortified foods such as orange juice with added vitamin C, vitamin E, or calcium, a variety of yogurts with probiotics, and performance-functional foods such as Gatorade, another item offered on the clear-liquid menu at MSKCC.

Foodservice directors are able to provide more hotel-style food and nutrition services in hospitals today with advances in technology. Many departments utilize an integrated computerized system to manage inventory, purchasing, recipe development, production, food ordering, and menu analysis. For instance, our patients can order their meals by telephone, and their order is automatically transmitted into the kitchen at three remote stations—hot, cold, and expeditor. If a patient is unwilling or unable to order by telephone, the Room Service Associate can take the order at bedside and transmit this order to the kitchen from the patient pantry, utilizing wireless technology. In some institutions patients can order their meal utilizing wireless technology connected to their in-room television. Also, communication between the kitchen and the patient units are made easier with the use of Nextel radios, cell phones, and beepers.

Aiding the Hospital’s Mission

Many foodservice directors are reaping great results from implementing customer-centric programs in their facilities. Patient satisfaction scores have soared, and patients are consuming more food. For example, MSKCC began using the Press Ganey benchmarking program to measure patient satisfaction in 2001. After implementing room service, the score jumped from the 25th percentile in 2001 to the 99th percentile in 2003 (Lawn, 2003; Weisberg, 2005). We still maintain a patient satisfaction score in the 99th percentile.

Overall meal consumption increased from only 30% of patients consuming 50% of their food on the main plate in 2001 to more than 80% of the patients in 2003 (McLymont et al., 2003). If the foodservice department provides services at a level equal to the medical care provided at the hospital, the foodservice personnel can feel confident that they are not only supporting but also uplifting the hospital’s mission.

by Sharon A. Cox , R.D., President of the National Society for Healthcare Foodservice Management, is Director, Food and Nutrition Services, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave., New York, NY 10021 ([email protected]).

References

Anonymous. 2006. “Pods” speed trays at Wakemed. Food Mgmt., April, p. 20.

Buzalka, M. 2006. Pursuing a liberal agenda. Food Mgmt., April pp. 28-36.

Caithamer, S. 2004. White glove food service. Today’s Dietitian, June, pp. 22-35.

Dupertuis, Y.M., Genton, L., Kossovsky, M.P., Kyle, U.G., Raguso, C.A., and Pichard C. 2003. Food intake in 1707 hospitalized patients: A prospective comprehensive hospital survey. Clin. Nutr. 22(2): 115-123.

Jatho, J., McNamee, C.K., and Petnicki, P.J. 1998. Benefits of a just-in-time spoken patient menu. J. Am. Dietet. Assn. 98(9): A11.

Keffe, S. 2005. From a hotel near you. Advance for Nurses, Dec., pp. 33 and 39.

Lang, J. 2004. A new face for food service. Foodservice Director, Dec.15, p. 41.

Lawn, J. 2003. The room service solution. Food Mgmt. 38(12): 24-28.

McLymont, V., Cox S., and Stell, F. 2003. Improving patient meal satisfaction with room service meal delivery. J. Nursing Care Qual. 18(1): 27-37.

Severson, K. 2006. For hospital menus, overdue surgery. New York Times, March 7.

Sheehan-Smith, L. 2006. Key facilitators and best practices of hotel-style room service in hospitals. J. Am. Dietet. Assn. 106: 581-586.

Weisberg, K. 2005. A remedy for patient meals: Memorial Sloan-Kettering aims to increase meal intake. Foodservice Director, April 15, p. 32.