Moving Forward on Sodium Reduction

Health advocates and policy makers continue to push for lower daily sodium consumption even though some researchers caution that certain levels might be too low. At the same time, food manufacturers are trying to overcome formulation challenges to develop better-tasting low- and reduced-sodium products.

Salt provides a number of functions in food formulation and cooking, including flavor enhancement and preservation properties. It also helps regulate water balance, contraction of muscles, conduction of nerve impulses, and osmotic pressure in the body. Despite the beneficial roles salt plays in food production and human biochemistry, it is considered public enemy number one by doctors and policy makers who say it may contribute to the development of high blood pressure and other health conditions, and they are calling on the food and restaurant industries to do something about it.

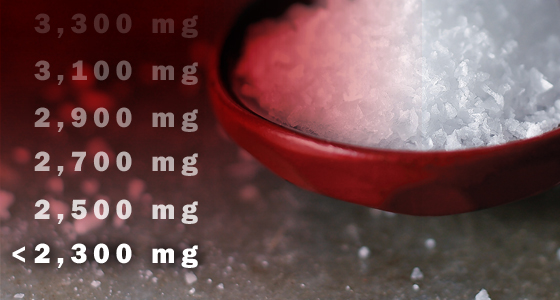

The problem is that we like salt too much. Americans age 2 and older consume on average 3,400 mg of sodium a day (USDA, 2012), while the Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends reducing daily sodium intake to less than 2,300 mg (USDA/HHS, 2010). Europeans, too, consume well in excess of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommended daily amount of less than 2,000 mg of sodium (EC, 2012, WHO, 2012). Around the world, 88% of adults exceed the amount of sodium recommended by WHO by more than 1,000 mg per day, and 75% of adults eat almost twice the amount of sodium a day that the American Heart Association (AHA) recommends (AHA, 2013a). This love affair with sodium might not be entirely by choice. Humans are hardwired for different taste attributes, says Robert Sobel, Director of Technology and Innovation for FONA International, so at a very early age, we need to consume sodium, and continue this throughout our lives to maintain proper functioning of our biochemistry. “Scientists believe that salt perception is associated with minerals, and that if we don’t have sodium in our diet it is just as bad as having too much sodium,” says Sobel. “Our muscles require sodium and potassium to function properly.”

Government officials around the world are taking action against the overconsumption of sodium while food manufacturers continue to tweak their formulations and look for new and improved ways to reduce sodium in food products. Researchers continue to investigate the roles that sodium plays in diet and human health, with some finding high sodium consumption associated with the development of various adverse health conditions and others concluding that reducing dietary sodium too much may not be healthy either. As the debate over sodium consumption and health continues, scientists are developing novel approaches to low-sodium product applications.

Calls to Lower Sodium Intake

Every five years since 1980, the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services (HHS) publish the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Over the years, some of the advice about healthy eating has changed due to new insights regarding nutrition and health. The guidelines regarding sodium intake have evolved over the years, from “avoid too much sodium” in the 1980 edition to “reduce daily sodium intake to less than 2,300 mg and further reduce intake to 1,500 mg among persons who are 51 and older and those of any age who are African American or have hypertension, diabetes, or chronic kidney disease” (USDA/HHS, 1980; USDA/HHS, 2010). Rachel Cheatham, Senior Vice President of Nutrition Communications for Weber Shandwick and adjunct assistant professor at Tufts University’s Friedman School of Nutrition, Science, and Policy, who spoke about taking action on dietary guidance at the IFT Wellness 13 event in February 2013, speculates that perhaps the actual recommendation for everyone might be changed to 1,500 mg when the Dietary Guideline for Americans is published in 2015. Of course, she says, this will be determined ultimately by the committee of scientific experts, who will analyze the latest nutrition research. The AHA already recommends that people aim to consume less than 1,500 mg of sodium per day, and it states that at this level, there would be a 26% decrease in high blood pressure (AHA, 2013b).

Responding to a request from Congress to recommend ways to reduce sodium to the levels suggested by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies in 2010 published a report in which it called for the Food and Drug Administration to set mandatory national standards for the sodium content of foods and for the food industry to voluntarily reduce sodium in foods prior to issuance of mandatory standards (Henney et al., 2010). The authors explain that the preference for salty taste can be changed with incremental reductions in sodium over time so that most consumers’ taste sensors will adjust to the lower levels. All food manufacturers and foodservice providers should be required to meet the standards, they say, to create a “level playing field” with the entire food industry held to the same sodium reduction requirements, eliminating any disadvantages.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

In addition to processed foods and restaurant foods, school breakfasts and lunches are targeted for containing too much sodium. The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 sets nutrition standards for the National School Lunch Program and National School Breakfast Program, most of which went into effect beginning with the 2012–2013 school year. The reduction of sodium will take place in three stages beginning in the 2014–2015 school year to allow the food industry to reformulate the products and for school children to become used to the reduced sodium as well as to give the USDA time to review data about the effects of sodium intake on human health (USDA, 2013).

High dietary sodium is not just a concern in the United States; global organizations and governments (particularly those of European countries) and researchers are developing strategies to help people lower their sodium intake and encourage food manufacturers to reduce the amounts of added sodium in food products. The WHO in January 2013 announced new guidelines regarding dietary sodium, stating that adults should consume less than 2,000 mg of sodium a day (WHO, 2012; WHO, 2013). Concerned that many Europeans are consuming in excess of the WHO daily sodium recommendations, the European Commission has developed the European Union Framework for National Salt Initiatives to address a general approach to meet either national or the WHO recommendations on sodium reduction (EC, 2012). The framework identifies certain food categories like bread, meat products, cheeses, and ready meals that are said to contribute to salt intake as products for sodium reduction; sets a goal for sodium reduction at a minimum 16% over four years; and encourages governments to work with food manufacturers in their efforts to reduce the sodium content of their products.

In addition to the industry setting goals to reduce the sodium content in food products, research presented at the World Heart Federation World Congress of Cardiology in April 2012 called for additional taxes on products that contain salt sold in many developing countries (WHF, 2012). If both the voluntary industry

reductions of sodium and the tax are implemented, the researchers from Harvard School of Medicine who presented the study say this could reduce the number of deaths from cardiovascular disease in countries like China and India.

These organizations have based their recommendations in part on the growing body of research linking high sodium consumption with the risk of developing adverse health conditions like damaged blood vessels and hypertension (Forman et al., 2012), cardiovascular disease and ischemic heart disease mortality (Yang et al., 2011), and lower levels of calcium in the body (Pan et al., 2012). Using computer models, Coxson et al. (2013) showed that gradually reducing sodium consumption by 40% to about 2,200 mg per day over 10 years could save hundreds of thousands of lives. Researchers have also reported a link between salt and the development of autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis (Wu et al., 2013, and Kleinewietfeld et al., 2013), but in a press announcement about the newly published studies, the researchers said that their findings “so far cannot predict the effect of salt on human autoimmunity” and that there could be other cell types and environmental factors that play roles in the development of autoimmune diseases (Nature, 2013).

These organizations have based their recommendations in part on the growing body of research linking high sodium consumption with the risk of developing adverse health conditions like damaged blood vessels and hypertension (Forman et al., 2012), cardiovascular disease and ischemic heart disease mortality (Yang et al., 2011), and lower levels of calcium in the body (Pan et al., 2012). Using computer models, Coxson et al. (2013) showed that gradually reducing sodium consumption by 40% to about 2,200 mg per day over 10 years could save hundreds of thousands of lives. Researchers have also reported a link between salt and the development of autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis (Wu et al., 2013, and Kleinewietfeld et al., 2013), but in a press announcement about the newly published studies, the researchers said that their findings “so far cannot predict the effect of salt on human autoimmunity” and that there could be other cell types and environmental factors that play roles in the development of autoimmune diseases (Nature, 2013).

While studies like these show the potential health risks of consuming high dietary sodium, Morton Satin, Vice President of Science and Research at Salt Institute, points out evidence that suggests that consuming too little sodium in the diet may lead to ill-health effects, too, and says that he would like to see the studies considered in decisions about dietary sodium regulations because “anything below our current level of salt consumption will place us in a zone of increased risk for a whole range of negative outcomes.” (Salt Institute is a nonprofit trade association that advances the benefits of salt in nutrition, water quality, and winter roadway safety.)

Satin cites research that found diets low in sodiummay increase the risk of metabolic syndrome by inducing changes in the plasma lipoproteins and inflammatory markers (Nakandakare et al., 2008), cardiovascular disease deaths (Stolarz-Skrzypek et al., 2011), and insulin resistance by activating the renin–angiotensin–

aldosterone and sympathetic nervous systems (Garg et al., 2010). Another study concludes that diets that are both high and low in sodium can put people with heart disease or diabetes at risk of stroke, heart attack, cardiovascular death, and hospitalization for congestive heart failure (O’Donnell et al., 2011). The researchers do question whether people who consume moderate/average amounts of sodium should reduce the amount further to lower rates of heart disease and stroke, and they suggest a large randomized controlled study be conducted.

Consumers’ Views on Dietary Sodium

Many consumers are at least aware of the issue of reducing dietary sodium, due in part to publicity generated by the various organizations and policy makers. Those watching their sodium intake are likely to be older, and as the population of those aged 65 and older is expected to increase more than 17% from 2013 to 2018, this becomes a potential growth area for low-sodium foods, according to Mintel’s Attitudes Toward Sodium report (Mintel, 2013). More than half (58%) of the respondents (U.S. adults) to Mintel’s survey are limiting their sodium intake. The report also cites some gender differences, with women more likely than men to watch how much sodium they consume because of concerns about gaining weight and men more likely than women to watch their sodium intake because their doctors told them to do this. In other words, women tend to choose to limit sodium and men have to limit theirs, Mintel concluded.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Other information about consumers’ sodium intake that Mintel reported refers to how consumers limit sodium. The majority of them use less salt. Others review the nutrition information on packages and menus to learn about sodium content. Women are more likely than men to do both, with Mintel reporting this could be due to more women being responsible for cooking and grocery shopping than men.

Two things that those surveyed for the research are not doing as frequently to reduce sodium in their diets are buying fewer packaged foods and eating out less at restaurants. According to the USDA and HHS, reducing consumption of processed foods and eating less at restaurants are actually the two ways in which consumers could significantly affect their sodium intake. The amount of salt that people add at the table or during home cooking is small compared to the amount they consume from processed foods, state the organizations (USDA/HHS, 2010). Specifically, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that 77% of the sodium that Americans consume comes from processed, prepackaged, and restaurant foods, 6% is added at the table, 5% is added during home cooking, and 12% occurs naturally (CDC, 2012).

In recent years, food manufacturers have released a number of low- and reduced-sodium products across many product categories. Mintel’s Global New Products Database (GNPD) tracks global product introductions with a low-, no-, or reduced-sodium claim and found that they increased almost 115% from 2005 to 2008 due to public health initiatives to educate consumers about the potential risks of high sodium intake (Mintel, 2009). However, its most recent research shows that the number of these claims has decreased 5% during 2010–2011, making up just 2% of total global food launches, a decline perhaps due in part to poor sales and challenges in finding suitable salt replacers (Mintel, 2012). Cheatham offers another possible explanation: early on, food manufacturers were making public statements about their sodium reduction efforts, but some have begun to take a “stealth health approach” by reducing sodium in the food products without marketing them to consumers as being lower in sodium.

Demonstrating Ways to Enhance Saltiness

In the past, low-sodium products were formulated with a blend of sodium and potassium chlorides, but the latter often imparts bitter and metallic tastes. Over time, scientists have developed a number of ingredients and techniques to improve foods made with low or reduced sodium.

“When you eat salt, only about 25% of that salt actually dissolves and is perceived; the remainder is swallowed,” explains Sobel, who spoke about ways to enhance the saltiness in foods at the IFT Wellness 13 conference. The key is to increase the bioavailability of salt while reducing the amount of it that is needed. Changing the structure of salt such as forming a microsphere with nanocrystals of salt can influence how consumers perceive the intensity because this new structure has a greater surface area and dissolves much faster, thereby boosting the perception of saltiness, adds Sobel. Creating a heterogeneous spatial distribution of salt within a product—“hot spots” of sodium so other bites of the product have a carryover effect—is another technique Sobel points to as a way to increase salt perception.

“When you eat salt, only about 25% of that salt actually dissolves and is perceived; the remainder is swallowed,” explains Sobel, who spoke about ways to enhance the saltiness in foods at the IFT Wellness 13 conference. The key is to increase the bioavailability of salt while reducing the amount of it that is needed. Changing the structure of salt such as forming a microsphere with nanocrystals of salt can influence how consumers perceive the intensity because this new structure has a greater surface area and dissolves much faster, thereby boosting the perception of saltiness, adds Sobel. Creating a heterogeneous spatial distribution of salt within a product—“hot spots” of sodium so other bites of the product have a carryover effect—is another technique Sobel points to as a way to increase salt perception.

Other scientists are investigating the effects of certain flavor/aroma compounds on perceived saltiness. More specifically, saltcongruent compounds may enhance salt perception without significantly affecting the flavor profile of the food product. Batenburg and van der Velden (2011) found that adding meat flavorings to reduced-sodium chicken and beef broths did help to increase the salt perception in some cases. The researchers then tested the salt-congruent compounds in the flavorings and found they were able to achieve a 15% reduction in sodium when sotolon, an aroma compound that when used at low concentrations has a maple syrup aroma, was used on its own and a 30% reduction when sotolon was used with mineral-based sodium replacers. The researchers acknowledge that the level of sodium reduction may not meet some of the guidelines set forth by several organizations and that additional research is needed. Sobel refers to other aroma compounds and mixtures as “phantom aromas,” tasteless aroma compounds that may influence the perception of a certain taste mode, be it salty, sweet, or sour, when used at very low levels. An example Sobel mentions is vanillin, which is associated with sweetness. “If you ask people what it smells like, they will say sweet, but we perceive sweetness on our tongue.” While some studies point to the use of salt-associated odors like bacon, anchovy, sardine, and cheese to heighten saltiness in low-sodium foods, the results of experiments on the use of these compounds are mixed, Sobel cautions, and the effectiveness of using these aroma compounds is thought to be due to the sodium concentration in the food product.

Research suggests that compounds from ingredients like yeasts and glutamates present in umami-rich foods like mushrooms, aged cheeses like parmesan, soy sauce, kombu, and tomatoes may contribute to salt perception. One of the relatively new approaches to ingredient development for low-sodium applications that Sobel notes involves preparing salty- and umami-tasting extracts from certain aqueous plants. Scientists in Korea analyzed the extracts of 13 plants and found that three of the plants (saltwort, sea tangle, and kukoshi) contained salty- and umami-tasting extracts that showed potential as sodium substitutes (Lee, 2011). The extracts were spray dried, and the resulting powders were mixed together into what the researchers called the plant salt substitute. The results showed that the plant salt substitute had a relative saltiness of 65% compared to sodium chloride, with the plant salt substitute containing 43% less sodium than sodium chloride. More research on the use of these extracts in food products is needed.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Even though these ingredients show promise in helping consumers reduce dietary sodium, there is the matter of cost to consider. “Salt is very, very cheap, and the majority of the different technologies are not,” emphasizes Sobel. And developing low- or reduced-sodium products with acceptable taste continues to challenge the industry since many consumers believe that low-sodium products do not taste that good, according to Cheatham. Still, as the health advocates and policy makers continue to warn about the potential health hazards that may result from consuming too much sodium, ingredient suppliers are dedicating resources to develop low-sodium technologies and ingredients (see sidebar on page 42), and food manufacturers like PepsiCo have reduced sodium in certain products; PepsiCo has also pledged to improve the nutritional profile of many of its brands in several global markets by 25% by 2015 (PepsiCo, 2010). The debate on the issue will certainly continue, especially as policy makers around the world continue to push for lower-sodium contents in food products.

Sodium Reduction Ingredient Solutions

Ingredient suppliers have developed a number of ways that food manufacturers can lower sodium but still provide consumers with acceptable products.

• AkzoNobel (www.akzonobel.com/saltspecialties) developed its OneGrain technology to combine regular salt, a salt replacer, and taste-enhancing flavors in single salt grains to achieve up to 50% sodium reduction. Suprasel Loso OneGrain, produced using the technology, can provide a one-for-one replacement for regular salt, and the company says that the ingredient is a genuine replacement for salt in terms of taste and functionality.

• AkzoNobel (www.akzonobel.com/saltspecialties) developed its OneGrain technology to combine regular salt, a salt replacer, and taste-enhancing flavors in single salt grains to achieve up to 50% sodium reduction. Suprasel Loso OneGrain, produced using the technology, can provide a one-for-one replacement for regular salt, and the company says that the ingredient is a genuine replacement for salt in terms of taste and functionality.

• To increase the umami, or savory, taste in foods without added sodium, Biorigin (www.biorigin.com) features its Bionis line of yeast extracts. The company reports that the ingredients can improve the mouthfeel and body in applications like soups, broths, sauces, salty snacks, tomato derivatives, and meat.

• Using a patent-pending compacting technology, Cargill (www.cargill.com) combines salt and other ingredients into clustered, thin flakes that have uniform

consistency, low bulk density, high solubility, and a large surface area. Sold under the FlakeSelect™ portfolio, these ingredients can be used in a range of food products like salty snacks, bakery, and seasoning blends for meat products. They are available in four varieties: FlakeSalt KCl, FlakeSalt KCl/Salt, FlakeSalt KCl/Sea Salt, and FlakeSalt Sea Salt.

• Reducing sodium in baked goods is challenging because of the important roles that sodium plays. Innophos (www.innophos.com) offers calcium phosphates

and sodium aluminum phosphates that can be used to reduce sodium in chemically leavened bakery products. These ingredients like Cal-Rise® calcium acid pyrophosphate, Regent 12XX® monocalcium phosphate, monohydrate, Levair® sodium aluminum phosphate, and more replace some or all of the traditional leavening agents in a variety of baked goods applications. Each ingredient has its own benefits, some of which are improved texture, resilient crumb structure, and better stability.

• Jungbunzlauer (www.jungbunzlauer.com) in February 2013 announced a new ingredient solution for low-sodium meat products. Its sub4salt Cure combines sub4salt mineral salts blend with sodium nitrate to replace curing salt. The ingredient is said to cure meat products with up to 35% less sodium without affecting the taste, texture, and microbiological stability of the finished product.

• LycoRed (www.lycored.com) has created an ingredient, Sante, from certain flavoring components in tomatoes to boost and enhance the flavor while allowing for sodium reduction in applications like soups. The company reports that it was able to replace 0.2% of monosodium glutamate in a standard

chicken soup mix with an equivalent amount of Sante to reduce the sodium content of the soup mix by 25%.

• For consumers, Morton Salt (www.mortonsalt.com) offers Morton® LiteSalt™ Mixture, a blend of sodium chloride and potassium chloride that contains 50% less sodium than regular salt, and Morton Salt Balance® Salt Blend, a blend of sodium chloride and potassium chloride with 25% less sodium than regular salt.

• Tate & Lyle (www.tateandlyle.com) offers SODA-LO™, which is manufactured using proprietary technology that turns salt crystals into free-flowing crystalline microspheres. The benefit of this ingredient, according to the company, is that the smaller crystals optimize saltiness perception in foods by maximizing the surface area relative to volume, allowing for an up to 50% reduction in sodium in some applications. The company also emphasizes that since the ingredient is made from salt, it does not impart any offtastes. It functions well in breads, breadings, and coatings, and salty snacks.

• In many cases, food manufacturers rely on potassium chloride to reduce sodium; however, the ingredients impart metallic or bitter aftertastes. Wixon (www.wixon.com) offers flavor enhancers/maskers to combat this under its Mag-nifique line. These include Mag-nifique Salt-Away and Mag-nifique Mimic. The company also highlights the use of umami to reduce sodium with its Wix-Fresh™ Umami, a proprietary blend of flavor ingredients that is said to boost savory notes and increase salt perception in meat products.

Karen Nachay, a Member of IFT,

Karen Nachay, a Member of IFT, is Associate Editor of Food Technology magazine

([email protected]).

References

AHA. 2013a. Adults worldwide eat almost double daily AHA recommended amount of sodium. Press release, March 21. American Heart Association, Dallas, Texas.

AHA. 2013b. Sodium (salt or sodium chloride). www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/NutritionCenter/HealthyDietGoals/Sodium-Salt-or-Sodium-Chloride_UCM_303290_Article.jsp.

Batenburg, M., and van der Velden, R. 2011. Saltiness enhancement by savory aroma compounds. J. Food Sci. 76(5): S280-S288.

CDC. 2012. Sodium and food sources. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga. www.cdc.gov/salt/food.htm.

Coxson, P.G., Cook, N.R., Joffres, M., Hong, Y., Orenstein, D., Schmidt, S.M., and Bibbins-Domingo, Kirsten. 2013. Mortality benefits from U.S. population-wide reduction in sodium consumption: projections from 3 modeling approaches. Hypertension 61(3): 564-570.

EC. 2012. Survey on members states’ implementation of the EU salt reduction framework. April. European Commission, Brussels, Belgium.

Forman, J.P., Scheven, L., de Jong, P.E., Bakker, S.J.L., Curhan, G.C., and Gansevoort, R.T. 2012. Association between sodium intake and change in uric acid, urine albumin excretion, and the risk of developing hypertension. Circulation 125: 3108-3116.

Garg, R., Williams, G.H., Hurwitz, S., Brown, N.J., Hopkins, P.N., and Adler, G.K. 2010. Low-salt diet increases insulin resistance in healthy subjects. Metabolism 60(7): 965-968.

Henney, J.E., Taylor, C.L., and Boon, C.S. 2010. Strategies to reduce sodium intake in the United States. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.

Kleinewietfeld, M., Manzel, A., Titze, J., Kvakan, H., Yosef, N., Linker, R.A., Muller, D.N., and Hafler, D.A. 2013. Sodium chloride drives autoimmune disease by the induction of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nature. First published online March 6, doi: 10.1038/nature11868.

Lee, G.-H. 2011. A salt substitute with low sodium content from plant aqueous extracts. Food Res. International 44(2): 537-543.

Mintel. 2009. Pass the salt? Mintel research shows sodium usage starting to change its course. Press release, Aug. 11. Mintel, Chicago, Ill.

Mintel. 2012. Low/no/reduced sodium NPD claims decline despite salt concerns. Press release, August. Mintel, London, UK.

Mintel. 2013. Attitudes toward sodium—U.S.—February 2013 executive summary.

Nakandakare, E.R., Charf, A.M., Santos, F.C., Nunes, V.S., Ortega, K., Lottenberg, A.M.P., Mion Jr., D., Nakano, T., Nakajima, K., D’Amico, E.A., Catanozi, S., Passarelli, M., and Quintão, E.C.R. 2008. Dietary salt restriction increases plasma lipoprotein and inflammatory marker concentrations in hypertensive patients. Atherosclerosis 200(2): 410-416.

Nature. 2013. Salt linked to autoimmune diseases. Press release, March 6. Nature Publishing Group, London, UK.

O’Donnell, M.J., Yusuf, S., Mente, A., Gao, P., Mann, J.F., Teo, K., McQueen, M., Sleight, P., Sharma, A.M., Dans, A., Probstfield, J., and Schmieder, R.E. 2011. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion and risk of cardiovascular events. JAMA 306(20): 2229-2238.

Pan, W., Borovac, J., Spicer, Z., Hoenderop, J.G., Bindels, R., Shull, G.E., Doschak, M.R., Cordat, E., and Alexander, R.T. 2012. The epithelial sodium/proton exchanger, NHE3, is necessary for renal and intestinal calcium (re) absorption. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 302: F943-F956.

PepsiCo. 2010. PepsiCo unveils global nutrition, environment and workplace goals. Press release, March 22. PepsiCo Inc., Purchase, N.Y.

Stolarz-Skrzypek, K., Kuznetsova, T., Thijs, L., Tikhonoff, V., Seidlerová, J., Richart, T., Jin, Y., Olszanecka, A., Malyutina, S., Casiglia, E., Filipovský, J., Kawecka-Jaszcz, K., Nikitin, Y., and Staessen, J.A. 2011. Fatal and nonfatal outcomes, incidence of hypertension, and blood pressure changes in relation to urinary sodium excretion. JAMA 305(17): 1777-1785.

USDA/HHS. 1980. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 1980. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Washington, D.C., and U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C. www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/1980thin.pdf.

USDA/HHS. 2010. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2010.

USDA. 2012. What we eat in America. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service. www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=18349 and www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/12355000/pdf/0910/sodium%20intake%20reassessed%20for%202007-2008.pdf.

USDA. 2013. Final rule “nutrition standards in the national school lunch and school breakfast programs” questions & answers for program operators. Jan. 25. www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/governance/Policy-Memos/2012/SP10-2012ar6.pdf.

WHF. 2012. Tax on salt and voluntary industry reductions in salt content could reduce deaths from cardiovascular disease by 3 per cent in developing countries. Press release, April 21. World Heart Federation, Geneva, Switzerland.

WHO. 2012. Guideline: sodium intake for adults and children. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

WHO. 2013. WHO issues new guidance on dietary salt and potassium. Press release, Jan. 31.

Wu, C., Yosef, N., Thalhamer, T., Zhu, C., Xiao, S., Kishi, Y., Regev, A., and Kuchroo, V.K. 2013. Induction of pathogenic TH17 cells by inducible salt-sensing kinase SGK1. Nature. First published online March 6, doi: 10.1038/nature11984.

Yang, Q., Liu, T., Kuklina, E.V., Flanders, W.D., Hong, Y., Gillespie, C., Chang, M.-H., Gwinn, M., Dowling, N., Khoury, M.J., and Hu, F.B. 2011. Sodium and potassium intake and mortality among U.S. adults: prospective data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch. Intern. Med. 171(13): 1183-1191.