A Big Fat Dispute

New research disputes the decades-old assumption that fatty foods, particularly those containing saturated fats, are detrimental to health while market data illustrate what consumers think.

Since the promotion of low-fat diets and production of reduced-fat or fat-free versions of foods began in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Americans have become overweight and obese at epidemic levels: In 1980, approximately 14% of the U.S. population was obese; now, 40% of U.S. women and 35% of U.S. men are obese, accounting for half of the more than two-thirds of U.S. adults who are overweight or obese. This national weight management crisis is likely attributable to several factors, but among them are the assumption that fatty foods, particularly those containing saturated fats, are detrimental to health and should be limited in the diet and the elimination of saturated and other natural fats in foods and replacing them with poor substitutes such as partially hydrogenated oils, trans fat, and refined carbohydrates. Recent research suggests that the natural fats in foods are far better for health and weight management than these substitutes. As a result, more and more consumers and nutrition experts are embracing fat, including saturated fat, and the foods that inherently contain it.

A Saturated Tale

The campaign to reduce the amount of fat in the U.S. diet began in the 1970s when the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs held discussions and hearings on whether high-fat diets were the cause of the premature deaths of certain U.S. lawmakers. By 1980 those debates had led to the publishing of the first U.S. dietary guidelines, which advised Americans to reduce their consumption of fatty foods while simultaneously encouraging a high intake of carbohydrates. The scientific reasoning for this advice was based largely on the dubious evidence from nutrition and epidemiological studies conducted in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. Key among these was the Seven Countries Study by Ancel Keys, a physiologist at the University of Minnesota. Keys theorized that a population’s high incidence of elevated blood cholesterol levels, heart attacks, and stroke was precipitated by any diet high in fat—particularly saturated fat—and other lifestyle factors. The Seven Countries Study was fraught with problems (Teicholz 2014): the countries involved in the study were not selected randomly, data that disproved Keys’s theories on dietary fat and heart disease were discarded, and perhaps most importantly, epidemiological studies do not prove causation.

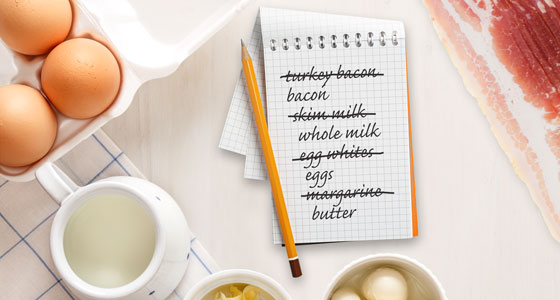

Nevertheless, somewhere along the way, the word “saturated” was removed altogether from Keys’s conclusions, and more imprecise generalizations about fats emerged—bolstered by the fact that a gram of fat contains nine calories while a gram of carbohydrate has only four calories. It did not take long for many to conclude that all dietary fats were bad, leading to heart disease and expanding waistlines, while any and all dietary carbohydrates were good. The food industry responded by inundating supermarkets with reduced-fat, low-fat, and fat-free foods produced by either removing fat altogether or replacing it with hydrogenated vegetable oils and/or refined carbohydrates. Skim milk was substituted for whole milk, butter was replaced with margarine, whole eggs were shunned for egg whites, and meals centered on meat and fish were exchanged for entrees based on refined carbohydrates (i.e., bread, pasta, potatoes, and white rice). “[W]hen the percent [of] fat is reduced in the diet, the percent of something else must increase (to add up to 100%); that something ended up being refined carbohydrates for the average American diet,” says Glen D. Lawrence, a biochemistry professor at Long Island University and author of the book The Fats of Life: Essential Fatty Acids in Health and Disease. To those with discriminating palates, many of the low-fat and fat-free foods did not taste good. “Removing fat from the diet makes food less appetizing, or as they say in the food industry, the food lacks ‘mouthfeel.’ Conse-quently the food industry found they needed to add sugar to foods to make them more palatable when fat was removed, so low-fat foods became sweeter,” Lawrence says. Furthermore, these types of foods had not been through any rigorous research studies to determine whether they were truly better for human health than full-fat foods. As it turns out, they weren’t.

Nevertheless, somewhere along the way, the word “saturated” was removed altogether from Keys’s conclusions, and more imprecise generalizations about fats emerged—bolstered by the fact that a gram of fat contains nine calories while a gram of carbohydrate has only four calories. It did not take long for many to conclude that all dietary fats were bad, leading to heart disease and expanding waistlines, while any and all dietary carbohydrates were good. The food industry responded by inundating supermarkets with reduced-fat, low-fat, and fat-free foods produced by either removing fat altogether or replacing it with hydrogenated vegetable oils and/or refined carbohydrates. Skim milk was substituted for whole milk, butter was replaced with margarine, whole eggs were shunned for egg whites, and meals centered on meat and fish were exchanged for entrees based on refined carbohydrates (i.e., bread, pasta, potatoes, and white rice). “[W]hen the percent [of] fat is reduced in the diet, the percent of something else must increase (to add up to 100%); that something ended up being refined carbohydrates for the average American diet,” says Glen D. Lawrence, a biochemistry professor at Long Island University and author of the book The Fats of Life: Essential Fatty Acids in Health and Disease. To those with discriminating palates, many of the low-fat and fat-free foods did not taste good. “Removing fat from the diet makes food less appetizing, or as they say in the food industry, the food lacks ‘mouthfeel.’ Conse-quently the food industry found they needed to add sugar to foods to make them more palatable when fat was removed, so low-fat foods became sweeter,” Lawrence says. Furthermore, these types of foods had not been through any rigorous research studies to determine whether they were truly better for human health than full-fat foods. As it turns out, they weren’t.

The Fats of Life

In order for the human body to survive, six nutrients are essential: water, vitamins, minerals, protein, carbohydrates, and fat. Fat is a major source of energy in the human body and is necessary for several bodily functions. It provides half of the energy the body needs at rest or during everyday activity. In the form of adipose tissue, fat insulates the body, thereby protecting vital organs from injuries due to external impacts and helping to maintain a normal core temperature. It provides structure and support for all cells in the body and promotes healthy skin and hair. For the proper digestion of food and absorption of certain nutrients, fat is imperative; without it, the body would be deficient in vitamins A, D, E, and K and unable to derive the full benefits of fat-soluble phytonutrients such as beta-carotene and lycopene. Moreover, because it comprises nearly two-thirds (60%) of the brain, fat is vital for proper brain development and maintenance. Some scientists have even suggested that certain types of fats are necessary for mental balance (Tarver 2014). What fat does not do, according to recent research, is make people fat—at least not on its own—or cause heart disease.

Lipids (the scientific name for fats) are made up of fatty acids that can be classified as saturated fatty acids and unsaturated fatty acids. All natural foods contain more than one type of fat. But in general, the main food sources of saturated fats include butter, cheese, coconut oil, eggs, meat, poultry, and whole milk. The main food sources of unsaturated fats include fish, nuts, seeds, certain fruits and vegetables, and certain vegetable oils. While saturated fats are solid at room temperature, two types of unsaturated fats—monounsaturated and polyunsaturated—are liquid at room temperature. A third type of unsaturated fat, trans fat, is solid at room temperature and may be the real cause for the correlation between fat consumption and poor health. From a food manufacturing standpoint, saturated fats are ideal; they are highly shelf stable and they provide texture and flavor. But when saturated fat was blamed for causing heart disease and obesity, food manufacturers needed an alternative. And while unsaturated fats are touted as better for human health, they are not suitable for producing shelf-stable foods: They spoil quickly and do not provide the same organoleptic properties to foods. However, through the process of partial hydrogenation, liquid unsaturated fats become more solid and, when used in foods, closely mimic the functionalities of saturated fats. These partially hydrogenated oils, which contain industrial (or artificial) trans fatty acids, were thought to be healthier than saturated fats because the partial hydrogenation allowed them to remain unsaturated (complete hydrogenation of vegetable oils turns them into saturated fats). However, not all unsaturated fats are created equal.

Lipids (the scientific name for fats) are made up of fatty acids that can be classified as saturated fatty acids and unsaturated fatty acids. All natural foods contain more than one type of fat. But in general, the main food sources of saturated fats include butter, cheese, coconut oil, eggs, meat, poultry, and whole milk. The main food sources of unsaturated fats include fish, nuts, seeds, certain fruits and vegetables, and certain vegetable oils. While saturated fats are solid at room temperature, two types of unsaturated fats—monounsaturated and polyunsaturated—are liquid at room temperature. A third type of unsaturated fat, trans fat, is solid at room temperature and may be the real cause for the correlation between fat consumption and poor health. From a food manufacturing standpoint, saturated fats are ideal; they are highly shelf stable and they provide texture and flavor. But when saturated fat was blamed for causing heart disease and obesity, food manufacturers needed an alternative. And while unsaturated fats are touted as better for human health, they are not suitable for producing shelf-stable foods: They spoil quickly and do not provide the same organoleptic properties to foods. However, through the process of partial hydrogenation, liquid unsaturated fats become more solid and, when used in foods, closely mimic the functionalities of saturated fats. These partially hydrogenated oils, which contain industrial (or artificial) trans fatty acids, were thought to be healthier than saturated fats because the partial hydrogenation allowed them to remain unsaturated (complete hydrogenation of vegetable oils turns them into saturated fats). However, not all unsaturated fats are created equal.

One type of unsaturated fat is consistently considered to be good for human health: monounsaturated fat. This is largely because of its prominent role in studies on Mediterranean diets. Found predominantly in olives, avocados, peanuts, peanut butter, rape seed, and oils derived from these foods, monounsaturated fats are said to help lower low-density lipoprotein levels in the blood and lower the risk of heart disease and stroke. They are also rich sources of vitamin E. In contrast, polyunsaturated fats can have both helpful and harmful effects on health. The two main types of polyunsaturated fatty acids are omega-3 fatty acids and omega-6 fatty acids. Both are essential for humans to consume as the human body is incapable of producing them on its own, and each has specific roles to play in human health. Studies indicate that omega-3 fatty acids—in particular, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapenta-enoic acid (EPA)—are imperative for proper development and function of the brain and reducing the risk of diseases associated with inflammation. DHA makes up a significant proportion of nerve-cell membranes and synapses in the central nervous system; it is the most abundant fatty acid in the brain. Both DHA and EPA have been found to have anti-inflammatory properties that fight cardiovascular disease by lowering blood pressure and triglyceride levels, improving the function of blood vessels, and decreasing the risk of cardiac arrhythmias. DHA and EPA may also be helpful in reducing the incidence of type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease (Swanson et al. 2012, Fiala et al. 2015). The third omega-3 fatty acid, alpha-linolenic acid, is used in the human body predominately for energy, and although the body can convert ALA to DHA and EPA, the process is inefficient and the conversion rate is poor (Bradbury 2011). By and large, the research on omega-3 fatty acids suggests that they are all beneficial to human health.

The same cannot be said of omega-6 fatty acids. Omega-6 fatty acids help maintain healthy hair, skin, and bones and metabolize into bioactive compounds that are integral to the body’s immune response (i.e., inflammation). Some studies indicate that omega-6 fatty acids may lower blood levels of total cholesterol, but in doing so they lower not only the level of low-density lipoproteins (the bad cholesterol) but also the level of high-density lipoprotein (the good cholesterol) (Credit Suisse Research Institute 2015). Other research suggests that omega-6 fatty acids are also pro-inflammatory, which means they could, to some extent, promote the inflammation that is the basis for cardiovascular disease and other noncommunicable chronic diseases such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes (Ramsden et al. 2013). “Omega-6 fatty acids can increase inflammation, and inflammation is at the root of most health problems. In addition, omega-6 [fatty acids] are highly susceptible to lipid peroxidation (spontaneous oxidation), which leads to atherosclerosis, cancer, and other adverse health effects,” Lawrence says. “Omega-6 [fatty acids] are essential and are needed in the diet in moderate quantities, [but] [t]hey can be toxic at high levels, just as vitamins can be toxic at high levels.” Moreover, there is an ongoing debate in the scientific community over whether an imbalanced ratio of omega-3 fatty acids to omega-6 fatty acids in the body plays a role in the presence or absence of several chronic conditions as well as faulty cognitive ability, including antisocial behavior (Tarver 2014). Because the main sources of omega-6 fatty acids are vegetable oils, most partially hydrogenated oils (namely, soybean, corn, cottonseed, and safflower oils) contain an abundance of omega-6 fatty acids (more than 50% composition); they also contain artificial trans fats.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

The Injurious Effect of Trans Fats

Even though partially hydrogenated oils were introduced in the Western diet decades ago as a safer—and cheaper—alternative to saturated fat, because they contain trans fats, it is now apparent that partially hydrogenated oils are not better for human health than saturated fats. Trans fats raise the level of low-density lipoprotein in the blood. In fact, an abundance of scientific research indicates that trans fat, particularly artificial trans fat, is the worst type of fat in the human diet because it has been consistently linked to cardiovascular disease (Credit Suisse Research Institute 2015, de Souza et al. 2015). Some trans fats occur naturally “in milk, beef, and products from other ruminants, such as sheep and goats,” Lawrence explains. “However, those trans fatty acids are different from the ones in partially hydrogenated vegetable oils, and they are, in fact, healthy and can decrease inflammation [and] asthma and help people lose weight.” But the main sources of trans fats in the U.S. diet are foods made with partially hydrogenated oils: According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), processed foods made with partially hydrogenated oils account for half of the trans fats that Americans consume. In an effort to remove such foods from the U.S. food system, in June 2015 the FDA removed partially hydrogenated oils from its list of food ingredients that are generally recognized as safe (food manufacturers have until June 18, 2018, to reformulate products or submit additive petitions for approval).

With clear scientific evidence that trans fats are detrimental to human health, there is a general consensus among scientists and policymakers that foods made with partially hydrogenated oils should be minimized in the diet as well as the food system. Where there is less consensus is on the issue of whether food manufacturers should revert to using—or maintaining the level of—saturated fats in foods or rely on other alternatives. The answer is not clear. And while U.S. nutritionists, physicians, and epidemiologists are conducting more studies and reviewing more data on saturated fat consumption in an attempt to determine the risks, if any, to health and waistlines, consumers are not waiting for their determination. As part of the movement toward natural, minimally processed foods with clean labels, consumers are embracing fatty foods and thus forging a new standard of which foods constitute a healthy diet. This new health paradigm involves eating more wholesome foods, regardless of fat content. What matters more is that the food is simple, real (i.e., no artificial ingredients), and as close to its natural form as possible.

Consumers Think for Themselves

Consumers therefore appear to be relying more on their own interpretation of what constitutes healthy food rather than facts, figures, and declarations from scientists and public health authorities. And according to the Credit Suisse Research Institute, when it comes to full-fat foods, they are probably right to do so. The research body recently released a report that states, “The stance of most officials and influential organizations such as [the World Health Organization] or [the American Heart Association] is now well behind research in two main areas: saturated fats and polyunsaturated omega-6 fats. … [S]aturated fat intakes is at worst neutral for [cardiovascular disease] risks” (2015). Two meta-analysis studies support this position, indicating that saturated fats do not increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and are not associated with all-cause mortality but polyunsaturated fats are (Chowdhury et al. 2014, de Souza et al. 2015). The report by the Credit Suisse Research Institute goes on to blame trans fats from partially hydrogenated vegetable oils for escalating cardiovascular disease risks and the increased intake of vegetable oils and carbohydrates for rising obesity. Lawrence agrees: “[H]igh-fat diets are more effective for weight loss and keeping weight under control than low-fat diets, and it would be preferable to have mostly saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids in the diet,” he asserts. “This goes completely against the cholesterol hypothesis ‘experts,’ but they no longer have a sound basis for their contention that lower saturated fats in the diet will improve health or increase longevity.”

U.S. public health authorities have been reluctant to accept the growing body of evidence that debunks the prevailing nutrition and dietary guidance on fat—especially saturated fat—that has been promoted to Americans for more than 30 years. The 2015–2020 U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans no longer recommends a limit on cholesterol intake but still advises Americans to eat fat-free and low-fat dairy products and to restrict consumption of saturated fats to less than 10% of daily calories (HHS/USDA 2015). A recently published study supports this dietary advice, concluding that saturated fat is associated with a greater incidence of overall mortality than unsaturated fats (this study does not establish causality) (Wang et al. 2016). That study also confirmed that trans fat—a type of unsaturated fat—has significant negative effects on health. Meanwhile, at least one European public health authority is reconsidering its fat stance: The British government has asked its scientific advisory committee on nutrition to review the fat-limiting advice in the Eatwell Guide, produced by Public Health England, to determine whether revisions may be necessary (Moss 2016). Despite authorities’ indecision, wholesome foods that naturally contain saturated fat are back on consumers’ grocery lists. As a result, butter, cheese, whole milk, eggs, and bacon are experiencing significant boosts in sales.

U.S. public health authorities have been reluctant to accept the growing body of evidence that debunks the prevailing nutrition and dietary guidance on fat—especially saturated fat—that has been promoted to Americans for more than 30 years. The 2015–2020 U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans no longer recommends a limit on cholesterol intake but still advises Americans to eat fat-free and low-fat dairy products and to restrict consumption of saturated fats to less than 10% of daily calories (HHS/USDA 2015). A recently published study supports this dietary advice, concluding that saturated fat is associated with a greater incidence of overall mortality than unsaturated fats (this study does not establish causality) (Wang et al. 2016). That study also confirmed that trans fat—a type of unsaturated fat—has significant negative effects on health. Meanwhile, at least one European public health authority is reconsidering its fat stance: The British government has asked its scientific advisory committee on nutrition to review the fat-limiting advice in the Eatwell Guide, produced by Public Health England, to determine whether revisions may be necessary (Moss 2016). Despite authorities’ indecision, wholesome foods that naturally contain saturated fat are back on consumers’ grocery lists. As a result, butter, cheese, whole milk, eggs, and bacon are experiencing significant boosts in sales.

Wholesome Fatty Foods

Wholesome Fatty Foods

Butter is about 70% saturated fat and contains high amounts of vitamins A, B12, D, E, and K as well as calcium, choline, potassium, and other essential nutrients. As a consequence, people around the world are abandoning margarine for butter, viewing it as more wholesome and far less processed than the partially hydrogenated vegetable oils that are still perceived to be the main ingredient in all margarines (leading brands of margarines are no longer made with partially hydrogenated oils). Perhaps no one is more aware of this trend than Unilever P.L.C., the world’s largest maker of margarines and spreads. The company’s sales of its margarine brands have been in steep decline in developed countries. Indeed, unit sales of margarine plummeted by 8.9% in the United States in 2015, which is part of a double-digit plunge in U.S. margarine sales since 2000. Conversely, dollar sales of butter in the United States have increased by more than 20% since 2013. According to sales data from IRI, a Chicago-based market research firm, sales of butter totaled $2.2 billion in 2013 and $2.7 billion by the end of 2015. In fact, global unit sales of butter have been increasing by 4% every year since 2010 and are expected to continue rising through 2020. Another sign of butter’s surging appeal is that McDonald’s Corp. announced in 2015 that it would begin using real butter instead of liquid margarine on all English muffins, biscuits, and bagels on its breakfast menu (McDonald’s Corp. 2015).

Consumers’ switch to wholesome foods includes a return to whole milk, which is rich in nutrients: Whole milk is about 3.5% fat, most of which is saturated (approximately 65%); it contains all of the essential amino acids, making it a complete protein; and it is a good source of calcium. In addition, two recent studies indicate that full-fat dairy benefits human health: One study determined that people who consume whole milk and other full-fat dairy products reduce their risk of developing type 2 diabetes by up to 46% while the other indicates that whole milk and other full-fat dairy products lower the risk of overweight and/or obesity by 8% (Rautiainen et al. 2016, Yakoob et al. 2016). Unit sales of whole fat milk increased by 4.5% last year, according to IRI.

Consumers’ switch to wholesome foods includes a return to whole milk, which is rich in nutrients: Whole milk is about 3.5% fat, most of which is saturated (approximately 65%); it contains all of the essential amino acids, making it a complete protein; and it is a good source of calcium. In addition, two recent studies indicate that full-fat dairy benefits human health: One study determined that people who consume whole milk and other full-fat dairy products reduce their risk of developing type 2 diabetes by up to 46% while the other indicates that whole milk and other full-fat dairy products lower the risk of overweight and/or obesity by 8% (Rautiainen et al. 2016, Yakoob et al. 2016). Unit sales of whole fat milk increased by 4.5% last year, according to IRI.

Perhaps due to Americans’ unwavering love of pizza, cheese never really experienced the significant dips in consumption that whole milk and butter did during the years of the low-fat craze. Nonetheless, cheese is experiencing a significant upswing in demand that is a direct result of consumers’ desire for natural foods and snacks. In the United States, cheese consumption has increased by more than 40% over the past two decades, and for the past four years, cheese has been one of the top five food categories that contribute most to supermarket sales (Daniels 2016). The main growth driver in the cheese market has been natural cheeses, not processed cheeses; in fact, U.S. consumption of processed cheeses has been dwindling since 2010. Demand for natural cheeses is so strong among U.S. consumers that grocers and supermarkets are expanding their cheese selections (Sidrane 2015). This will likely prove to be a prudent move as Mintel expects cheese sales to increase by 20% between now and 2020, reaching $27.7 billion.

The upswings in the sales of cheese and butter are strong, but neither is as significant as the meteoric rise in the demand for bacon. In the 1980s bacon, along with butter and whole milk, experienced a significant decline in consumption during the low-fat movement. Bacon’s prospects were tarnished even further when the adverse effects of nitrates were also propagated in the 1980s. The combination of the low-fat craze and the nitrate scare caused bacon sales to decline by as much as 40%, triggering the price of pork belly to drop to as low as $0.19 per pound. Over the past 10 years or so, bacon sales have grown to more than $4 billion in annual sales, and the main reason for bacon’s resurrection was the National Pork Board’s decision to market bacon as a flavor enhancer to fast-food restaurants. In the 1990s, fast-food establishments began cooking burgers to well done to avoid foodborne illness outbreaks from partially cooked beef. Apparently, well-done burgers did not taste that great, but adding a slice or two of bacon to the sandwiches vastly improved their taste appeal. Bacon’s reputation as a flavor enhancer grew, and by 2000, it had become the third most popular condiment (Sax 2014). Since then, bacon has expanded well beyond fast food and is being used to enhance the flavor of just about everything: cookies, ice cream, artisan doughnuts, Brussels sprouts, gravy, pizza, French fries, pasta, scallops, shrimp, and so on. As a result, consumers and foodservice operations have created bacon mania: IRI data indicate that unit sales of bacon increased by more than 5% between 2013 and the end of 2015. The demand has caused the price of a pound of bacon to increase from $3 a pound in 2005 to just under $6 a pound now. Besides its ability to augment the flavor of many different foods, bacon packs a lot of nutrients: About 40% of the fat in bacon is saturated and 60% is unsaturated (mostly monounsaturated), and it contains high levels of B vitamins, selenium, phosphorus, and choline as well as moderate levels of iron, magnesium, and zinc.

The upswings in the sales of cheese and butter are strong, but neither is as significant as the meteoric rise in the demand for bacon. In the 1980s bacon, along with butter and whole milk, experienced a significant decline in consumption during the low-fat movement. Bacon’s prospects were tarnished even further when the adverse effects of nitrates were also propagated in the 1980s. The combination of the low-fat craze and the nitrate scare caused bacon sales to decline by as much as 40%, triggering the price of pork belly to drop to as low as $0.19 per pound. Over the past 10 years or so, bacon sales have grown to more than $4 billion in annual sales, and the main reason for bacon’s resurrection was the National Pork Board’s decision to market bacon as a flavor enhancer to fast-food restaurants. In the 1990s, fast-food establishments began cooking burgers to well done to avoid foodborne illness outbreaks from partially cooked beef. Apparently, well-done burgers did not taste that great, but adding a slice or two of bacon to the sandwiches vastly improved their taste appeal. Bacon’s reputation as a flavor enhancer grew, and by 2000, it had become the third most popular condiment (Sax 2014). Since then, bacon has expanded well beyond fast food and is being used to enhance the flavor of just about everything: cookies, ice cream, artisan doughnuts, Brussels sprouts, gravy, pizza, French fries, pasta, scallops, shrimp, and so on. As a result, consumers and foodservice operations have created bacon mania: IRI data indicate that unit sales of bacon increased by more than 5% between 2013 and the end of 2015. The demand has caused the price of a pound of bacon to increase from $3 a pound in 2005 to just under $6 a pound now. Besides its ability to augment the flavor of many different foods, bacon packs a lot of nutrients: About 40% of the fat in bacon is saturated and 60% is unsaturated (mostly monounsaturated), and it contains high levels of B vitamins, selenium, phosphorus, and choline as well as moderate levels of iron, magnesium, and zinc.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

For decades, the consumption of eggs was on the decline due to their cholesterol content and the now discredited claim that eating cholesterol-laden foods such as eggs adversely affects blood levels of cholesterol (Wartman 2012, Lawrence 2013). In fact, the U.S. International Trade Commission at one point estimated that the cholesterol scare cost the U.S. egg industry $10 billion (Ferdman 2014). “[A]s more and more research has indicated that dietary cholesterol … may not raise blood cholesterol or heart disease risk in most people, egg consumption has been on the rise,” says Mitch Kanter, executive director, Egg Nutrition Center. “[M]ore and more folks are seeking out higher-protein options throughout the day, and carbohydrate-based breakfasts in particular have fallen somewhat out of favor.” Now, eggs are back in consumer diets for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. In the United States, per capita consumption has increased from 239.7 in 1998 to 263.6 (AEB 2016), and it is expected to grow to 300 by the year 2030 (Credit Suisse Research Institute 2015). Eggs are a compact, highly nutritious form of fat and protein; they contain all the B vitamins and the full range of amino acids that make up a complete protein. “In fact, the protein quality in eggs is often used as the gold standard against which all other protein sources, both animal- and non-animal-derived proteins, are measured. Eggs are also relatively low in calories; one large egg contains 70 calories,” Kanter adds. Moreover, eggs are a good natural source of certain micronutrients that are missing from many foods, such as iodine, choline, and vitamin D. They also contain the antioxidants lutein and zeaxanthin, which help prevent macular degeneration.

For decades, the consumption of eggs was on the decline due to their cholesterol content and the now discredited claim that eating cholesterol-laden foods such as eggs adversely affects blood levels of cholesterol (Wartman 2012, Lawrence 2013). In fact, the U.S. International Trade Commission at one point estimated that the cholesterol scare cost the U.S. egg industry $10 billion (Ferdman 2014). “[A]s more and more research has indicated that dietary cholesterol … may not raise blood cholesterol or heart disease risk in most people, egg consumption has been on the rise,” says Mitch Kanter, executive director, Egg Nutrition Center. “[M]ore and more folks are seeking out higher-protein options throughout the day, and carbohydrate-based breakfasts in particular have fallen somewhat out of favor.” Now, eggs are back in consumer diets for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. In the United States, per capita consumption has increased from 239.7 in 1998 to 263.6 (AEB 2016), and it is expected to grow to 300 by the year 2030 (Credit Suisse Research Institute 2015). Eggs are a compact, highly nutritious form of fat and protein; they contain all the B vitamins and the full range of amino acids that make up a complete protein. “In fact, the protein quality in eggs is often used as the gold standard against which all other protein sources, both animal- and non-animal-derived proteins, are measured. Eggs are also relatively low in calories; one large egg contains 70 calories,” Kanter adds. Moreover, eggs are a good natural source of certain micronutrients that are missing from many foods, such as iodine, choline, and vitamin D. They also contain the antioxidants lutein and zeaxanthin, which help prevent macular degeneration.

Fat has always been an essential nutrient for the human body, and when it was removed from foods, particularly the ones that inherently contain it, the incidence of overweight, obesity, and type 2 diabetes increased dramatically. Perhaps people consumed more food because they were simply not satiated (because fat increases the feeling of fullness) or, more likely, the ingredients used to replace saturated fat—partially hydrogenated oils and refined carbohydrates—are far more damaging to human health than saturated fat. Regardless, the proliferation of expanding waistlines along with a body of research questioning the link between saturated fat and cardiovascular disease imply that the adoption of low-fat and fat-free dietary patterns and foods has been a health and nutrition failure. As a result, fat is back and poised to figure prominently on Americans’ plates.

Toni Tarver is senior writer/editor of Food Technology magazine ([email protected]).

References

AEB. 2016. “About the U.S. Egg Industry.” http://www.aeb.org/farmers-and-marketers/industry-overview.

Bradbury, J. 2011. “Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA): an Ancient Nutrient for the Modern Human Brain. Nutrients 3(5): 529–554.

Chowdhury, R., S. Warnakula, S. Kunutsor, et al. 2014. “Association of Dietary, Circulating, and Supplement Fatty Acids With Coronary Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Ann. Intern. Med. 160(6): 398–406.

Credit Suisse Research Institute. 2015. Fat: A New Health Paradigm. Credit Suisse AG Research Institute, Zurich, Switzerland.

Daniels, J. 2016. “Butter Is Back, Bubbling up With Golden Demand.” CNBC, March 8.

de Souza, R. J., A. Mente, A. Maroleanu, et al. 2015. “Intake of Saturated and Trans Unsaturated Fatty Acids and Risk of All Cause Mortality, Cardiovascular Disease, and Type 2 Diabetes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies.” Brit. Med. J. 351:h3978 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h3978.

Ferdman, R. A. 2014. “Americans Once Ate Nearly Twice as Many Eggs as They Do Today.” Quartz, April 2.

Fiala, M., R. C. Halder, B. Sagong, et al. 2015. “ω -3 Supplementation Increases Amyloid-ß Phagocytosis and Resolvin D1 in Patients with Minor Cognitive Impairment.” FASEB J. 29(7): 2681–2689.

Lawrence, G. D. 2013. “Dietary Fats and Health: Dietary Recommendation in the Context of Scientific Evidence.” Adv. Nutr. 4(3): 294–302.

McDonald’s Corp. 2015. “McDonald’s to Fully Transition to Cage-Free Eggs for All Restaurants in the U.S. and Canada.” Press release, Sept. 9. McDonald’s Corp., Oakbrook, Ill.

Moss, R. 2016. “Diet Guidelines on Saturated Fat to Be Questioned Under New Government Review.” The Huffington Post UK, June 13.

Ramsden, C., D. Zamora, B. Leelarthaepin, et al. 2013. “Use of Dietary Linoleic Acid for Secondary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease and Death: Evaluation of Recovered Data from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and Update Meta-Analysis.” Brit. Med. J. 346:e8707 doi:10.1136/bmj.e8707.

Rautiainen, S., L. Wang, I.-M. Lee, J. E. Manson, J. E. Buring, H. D. Sesso. 2016. “Dairy Consumption in Association with Weight Change and Risk of Becoming Overweight or Obese in Middle-Aged and Older Women: a Prospective Cohort Study.” Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 103(4): 979–988.

Sax, D. 2014. “The Bacon Boom Was Not an Accident.” Bloomberg News, Oct. 6.

Sidrane, A. 2015. “The Consumer Cheese Choice.” Grocery Headquarters, Dec. 1.

Swanson, D., R. Block, and S. A. Mousa. 2012. “Omega-3 Fatty Acids EPA and DHA: Health Benefits Throughout Life.” Adv. Nutr. 3: 1–7.

Tarver, T. 2014. “A Diet for a Kinder Planet.” Food Technol. 68(10): 20–29.

Teicholz, N. 2014. “The Questionable Link Between Saturated Fat and Heart Disease.” The Wall Street Journal, May 6.

Wang, D. D., Y. Li, S. E. Chiuve, et al. 2016. “Association of Specific Dietary Fats With Total and Cause-Specific Mortality.” JAMA Intern. Med. July 5. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2417.

Wartman, K. 2012. “Sunny-Side up: in Defense of Eggs.” The Atlantic, Aug. 27.

Yakoob, M. Y., P. Shi, W. C. Willett, et al. 2016. “Circulating Biomarkers of Dairy Fat and Risk of Incident Diabetes Mellitus Among U.S. Men and Women in Two Large Prospective Cohorts.” Circulation 133(17): 1645–1654.