Mastering the Elements of Good Cooking

CULINARY POINT OF VIEW

While studying English at the University of California, Berkeley, Samin Nosrat splurged on a dinner at Chez Panisse that changed the course of her life. She got a job as a busser at the famous restaurant and gradually moved up through the ranks, ultimately becoming prep cook. She went on to study traditional Italian cuisine under Benedetta Vitali in Florence. She is also a practiced instructor, having taught well-known food writer Michael Pollan and many others how to cook. Now, with her first cookbook “Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat,” Nosrat expertly reduces the art and craft to a mastery of the four elements named in the title. “Salt, fat, acid, and heat are the four cardinal directions of cooking,” she writes, “and this book shows how to use them to find your way in any kitchen.”

Q: As the child of Iranian immigrants, did you grow up eating a lot of Persian dishes?

Samin Nosrat: My parents came over from Iran in 1976 and I was born in 1979 in San Diego. My mom’s an amazing cook so I grew up pretty much eating only Iranian food. I have always loved eating, but I don’t remember a very distinct interest in cooking before I kind of randomly started cooking professionally. So, for me, food was always this incredible thing bringing our family together. My mom would rotate between me and my two brothers asking us what we wanted for dinner that night, so we each got to choose. I think, for her, it was a really important part of our culture and a way to keep us aware of where we came from. But apart from helping our mom peel eggplants, we didn’t do a lot of cooking as kids. I was not at my mom’s apron strings as a little kid or anything like that.

Q: You went to college to study English. What led you to cooking?

Nosrat: I was an English major [at the University of California, Berkley] and my boyfriend and I ended up saving for this dinner to go to Chez Panisse, which I had never heard of. It was 1997, so it was before food blogs, celebrity chefs, and food trends, and it was kind of like the very beginning of the internet.

Eating there was an illuminating experience, both as a diner, but certainly as just a person experiencing what it is to be in a restaurant and be really cared for. It felt very similar to my experience of being cared for at home by my mom, which is not something you always get in a restaurant.

They could tell we were newbies in the dining room. When the server brought the dessert—a chocolate soufflé with this sauce—she asked, “Have you ever had soufflé before? Would you like me to show you how to eat it?” She told us to poke a hole in the top with a spoon, and then pour the sauce in—that way every bite gets sauce.

I was so inspired by the restaurant, and I had some friends who were bussers there, so I decided I wanted to apply for a job as a busser. When I returned to the restaurant, the floor manager was the soufflé server. We recognized each other and I was so eager, and I think she was probably desperate, because she asked, “Can you start tomorrow?” I started the next day as a busser. After a while, I thought maybe I would like to be a cook after graduation so I started volunteering in the kitchen, and then eventually, got hired in the kitchen.

Q: You are a writer, cook and teacher. Do you have an affinity to one more than the others?

Nosrat: It’s all really mixed up. I entered college wanting to be a writer, and I worked as a cook for the first 10 years after college, which meant that writing definitely took a backseat. But, even so, I did apply for Fulbright scholarship during that time. I went to Italy to help write a cookbook, and I was studying food writing. So, I’ve always tried to intertwine the two careers.

But then, in 2006, I took some classes at UC Berkeley’s School of Journalism with Michael Pollan, and he encouraged me to just start writing. So, I started writing for the Edible San Francisco, the San Francisco Chronicle, and then one by one, more and more. But up until I left restaurant cooking in 2009, if I introduced myself to people, I would say, “Oh, I’m a cook.” Now, my office is a writing office and I make the bulk of my money from writing. So, I’m all three.

Q: How’s your new cookbook different from the plethora of other cookbooks on the market?

Nosrat: I think of it as an un-cookbook in some ways. I knew it wasn’t going to be a typical cookbook with 150 recipes, eight chapters, and 45 pictures. That’s not how I think about cooking. My philosophy came to me while I was a cook at Chez Panisse, and it’s how I have filed away every lesson I’ve learned since then.

The cookbook is a distillation of my cooking experiences into a way to simplify and think about cooking. I can’t tell you how many times I’m at an event or just at someone’s house making a salad, and they tell me, “I don’t understand. Why does it taste so good?” And I say, “It’s lettuce, olive oil, vinegar. It’s just about getting the balance right.” Everything is all about salt, fat, acid, and heat. No matter what you cook, these are the four elements that we’re always using to guide us. Salt enhances flavor, fat carries flavor and makes a variety of wonderful textures possible, acid balances flavor, and heat ultimately determines the texture in our food. That’s how I think about cooking and that’s how I teach people to cook.

I wanted to try to create a roadmap for people to be able to understand what sensory cues to look for as they cook. And how to develop their palate so they know what it is that they’re tasting for. I felt that would be much more helpful than any sort of recipe I could perfect for anyone.

Q: There aren’t any photos in your cookbook, just illustrations. What’s the reason behind that choice?

Nosrat:I was teaching Michael Pollan how to cook for his book Cooked and he quickly picked up on my obsession with these four elements. He asked, “What is it, you and these four things … what’s your obsession?” I said, “Oh, well, that’s my system. That’s how I think about cooking. That’s how I teach people how to cook.” And he said, “You’ve got to turn that into a book.”

My immediate reaction was to say that I couldn’t do that because it would need to have beautiful photos. But I knew that the kind of book we were talking about couldn’t have beautiful photos. What is a photo in book? It’s some extremely proficient person having cooked the most perfect version of a thing and then styled it with the perfect lighting and the perfect props. Then someone takes a picture of it and in appears in your book as a pinnacle of a thing. And that’s beautiful, but that is sending a message that your thing should look like this most perfect version of this thing.

I knew that I would be writing a book in which I was trying to teach people to be a little bit more relaxed, that it doesn’t matter if you don’t have spinach because you can use chard. Or if you don’t have pork, you can use chicken. I just felt it would be a little bit disingenuous to pair this perfect thing with this message of looseness. Also, I had been a huge fan of this illustrator, Wendy MacNaughton. She’s so much more than just an illustrator; she’s a visual storyteller. I knew that this book would be about conveying information and helping people understand ideas and that’s exactly what she does.This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Grilled Artichokes

Serves 6

Recall the miraculous way Heat transforms the flavors of wood into the extraordinary flavors of smoke and you’ll intuit why any vegetable will be improved by time spent on the grill. But only a handful of them can be properly grilled from a raw state. Think of grilling as a finishing touch for most starchy or dense vegetables, such as these artichokes, fennel wedges, or baby potatoes. Treat them right, by parcooking them on the stove or in the oven until they are tender, then skewer and grill them for a dose of smoky aroma.

Ingredients

- 6 artichokes (or 18 baby artichokes)

- Extra-virgin olive oil

- 1 tablespoon red wine vinegar

- Salt

Set a large pot of water on to boil over high heat. Build a charcoal fire, or preheat a gas grill. Line a baking sheet with parchment paper.

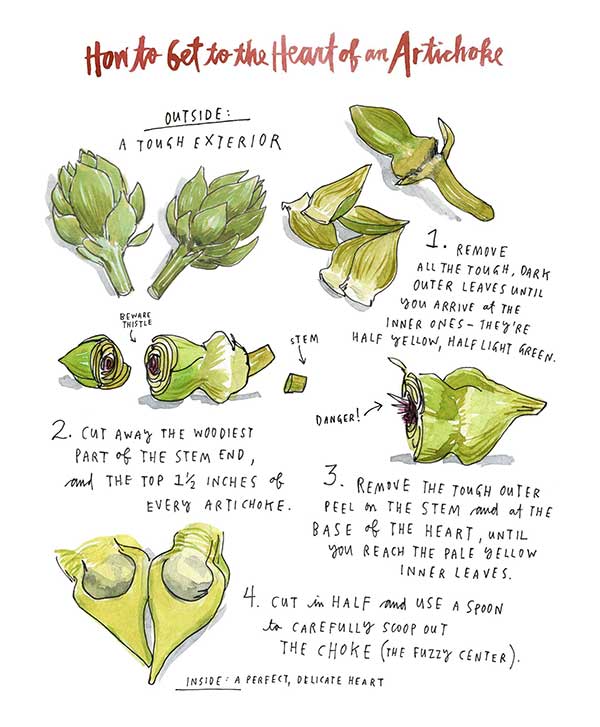

Remove the tough, dark outer leaves from the artichokes until the remaining leaves are half yellow, half light green. Cut away the woodiest part of the stem end and the top 1½ inches of every artichoke. If there are any purple inner leaves, cut them out, too. You may need to remove more in order to cut away everything fibrous. It might seem like you’re trimming a lot, but remove more than you think you should, because the last thing you want is to bite into a fibrous or bitter bite at the table. Use a sharp paring knife or a vegetable peeler to remove the tough outer peel on the stem and at the base of the heart, until you reach the pale yellow inner layers. As you clean them, place the artichokes in a bowl of water with the vinegar, which will help keep them from oxidizing, which makes them turn brown.

Cut the artichokes in half. Use a teaspoon to carefully scoop out the choke, or fuzzy center, then return the artichokes to the acidulated water.

Once the water has come to a boil, season it generously until it’s as salty as the sea. Place the artichokes in the water and reduce the heat so the water stays at a rapid simmer. Cook the artichokes until they are just tender when pierced with a sharp knife, about 5 minutes for baby artichokes and 14 minutes for large artichokes. Use a spider or strainer to carefully remove them from the water, and place them on the prepared baking sheet in a single layer.