Small Food Comes of Age

Enterprising entrepreneurs are carving out niches as aging megabrands lose momentum in the marketplace. Here’s a look at some rising stars who are challenging the status quo and the reasons why their timing couldn’t be better.

Article Content

In an era in which Big Food is eyed with suspicion by an evolving breed of savvy, sometimes cynical consumers looking to eat more transparently, healthfully, and naturally, the opportunities for small start-up ventures have never been greater. It’s not an exaggeration to call this the age of the entrepreneur. A broad array of resources—ranging from shared kitchens to food incubators to business accelerators—is available to support entrepreneurs, and venture capital is flowing freely in the direction of start-up companies with bright ideas and viable business plans. Since 2012, private consumer packaged goods companies have raised more than $8 billion from investors, according to data from research and strategy firm CB Insights (Caldbeck 2017).

“There’s so much activity. There’s such a rapid evolution in the food industry in terms of technology, in terms of brands. There’s never been a more exciting time,” says Lou Cooperhouse, executive director of the Rutgers Food Innovation Center, an incubator for food start-ups. A recent list of culinary incubators and accelerators includes nearly three dozen such operations scattered across the country (Lenhardt 2017). Certainly, Big Food has jumped on the Small Food bandwagon. Every week seems to bring news of another major food company unveiling a competition for start-ups or setting up a venture arm to invest in small companies with big potential.

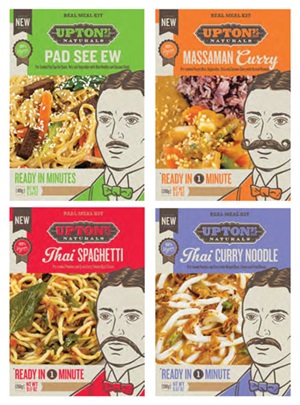

Financing a fledgling food company with someone else’s money is much easier than it was a decade or so ago, says Dan Staackmann, founder and CEO of Upton’s Naturals, a fast-growing maker of vegan meat substitutes that has been in business since 2005. “At this point, [potential investors] have been coming out of the woodwork,” says Staackmann. “We get one or two a week, calling or emailing. Everybody wants to know: are you looking for money?” At the Natural Products Expo this past spring, “we probably had 40 people trying to get our attention, looking for the next [big] thing,” he adds.

Three or four years ago it was rare to find a venture capital fund dedicated to food, but that has changed, says Erin Lenhardt, founder and CEO of The Food Mint, a consulting company for start-ups. “More and more people are approaching us to say [they] started a food-specific venture capital fund,” she notes.

“Now all of a sudden, we’re seeing investors that are investing in the food industry in a major way like we’ve never seen before,” Cooperhouse agrees. “The venture community and the corporate venture community are both paying a lot of attention to food entrepreneurship.”

Good for You in the Driver’s Seat

Driven by consumer interest, the lion’s share of entrepreneurial activity is focused on good-for-you premium products. Lenny Lebovich, who two years ago founded PRE Brands to bring a line of grass-fed meat products to market, likes to call it “food 2.0,” which he describes as “next generation” products and brands targeted to consumers who care deeply about what they’re putting into their bodies.

Lenhardt, who cofounded a start-up called Norm’s Farms that markets a variety of elderberry products, said she was drawn to the business because of her interest in eating more healthfully. “Good food is becoming an incredible trend,” she says. “Conditions are right for venture capitalists to make money in this space.”

Venture capital firm Obvious Ventures, for example, has identified healthy living as one of three focus areas, and within that framework, it has invested in plant-based food companies such as Beyond Meat and Miyoko’s Kitchen. “In the last 50 years, industrial Big Food has created success by optimizing for shelf life, by adding salt and sugar and preservatives,” says Obvious Ventures cofounder and managing director Vishal Vasishth. “We believe that the next 50 years is going to be a transformation from that kind of an approach to an approach which optimizes for nutrition.”

An incubator program introduced last year by yogurt maker Chobani is dedicated to helping start-ups that share Chobani’s vision of DNNA (delicious, nutritious, natural, and accessible) food. The Chobani incubator program offers a $25,000 no-strings-attached (i.e., equity-free) grant and a comprehensive curriculum that covers sales, marketing, finance, and operations.

An incubator program introduced last year by yogurt maker Chobani is dedicated to helping start-ups that share Chobani’s vision of DNNA (delicious, nutritious, natural, and accessible) food. The Chobani incubator program offers a $25,000 no-strings-attached (i.e., equity-free) grant and a comprehensive curriculum that covers sales, marketing, finance, and operations.

Navigating the Path to Success

Even with a growing network of resources available to support food start-ups, the path to successful entrepreneurship is not an easy one. Just getting chosen to participate in an incubator or accelerator program can be intensely competitive. Chobani’s food incubator program drew 450 applicants for the six spots in last year’s class, and this year, there were more than 500 applicants for the program.

According to the U.S. Small Business Administration (2016), only about half of small businesses survive 10 years or longer, and other sources put the failure rate even higher. “It’s really hard,” says Lenhardt, who started her elderberry business in 2011 and operates it along with her consultancy. “A lot of entrepreneurs get started from a place of passion,” she notes. “It’s not enough. … At the core of it, the biggest problem is finding product market fit—which means you have to build a product that the market wants.”

Cooperhouse of the Rutgers incubator has a similar perspective. “First of all, you need to have a great idea,” he emphasizes. “You need to make something that is consumer-driven, value-added, and differentiated … distinctive.” From there, an entrepreneur needs to have proof of concept, which is supporting evidence that the concept and business model are sound, as well as a plan to successfully scale up the business. Without all of the preceding in place, a company is unlikely to attract significant investment.

“You have to have a path for an investor to get a return. If you don’t have that path, you’re not going to get a lot of meetings,” said Andy Whitman, managing partner with packaged goods investment firm 2x Consumer Products Growth Partners, who spoke this spring at the Good Foods Conference and a Specialty Foods Assoc. (SFA) event in Chicago. For Whitman, the two key indicators of a company’s potential are gross margins and velocity (i.e., how products are moving at retail). The latter is more important than distribution, he said, because even with decent distribution, weak sales don’t bode well for business success. And without strong margins, a company won’t have the cash to reinvest in the business, Whitman said at the SFA event.

Entrepreneurs also need to think carefully about what they want from an investor, Whitman said, noting that in some cases an investor will expect to be involved as a business advisor, and if the entrepreneur isn’t looking for that level of involvement, it won’t be a good fit. Speaking at the Good Food Conference, he noted that start-up owners need to read the fine print before signing on to a deal that cedes eventual acquisition rights or an overly large share of ownership. “For a couple of million dollars, they shouldn’t have a path to ownership,” he stressed.

Luke Saunders, who founded prepared salad company Farmer’s Fridge in 2013, has been through several funding rounds, and this spring, he exchanged some company equity for a $10 million influx of capital from Danone Ventures and investment firm Cleveland Avenue. “We’re venture-backed, which makes sense for our business,” says Saunders. But he too advised entrepreneurs to proceed carefully as they seek funding sources. “I always tell anyone who asks that the first thing you should do is spend all of your own money. You really want to get your business far enough along that it’s investable. … If it’s not clear that your product is actually going to work in the marketplace, you can certainly get money, but it’s usually very expensive money. In other words, they want to buy a lot of your company for not a lot of money.”

On the other hand, it’s not uncommon in the current entrepreneur-friendly environment for a giant food company to make a major investment to scoop up a small food or beverage brand. Hormel Foods spent $286 million to acquire natural and organic nut butter company Justin’s last year, and Unilever acquired specialty condiment company Sir Kensington this spring. “Companies like Kraft Heinz or Unilever, they really struggle with innovation … to create and bring new products to market in the way that a start-up can do, so their strategy really is to acquire them,” says Lenhardt. “And they’re willing to pay a lot of money to participate in the clean ingredients, better-for-you food space.”

Another indicator of the strength of the entrepreneurial movement may be the quality of the employees it is attracting. Lebovich says he’s been pleasantly surprised at how easy it’s been to bring smart young talent into the fold at Chicago-based PRE Brands. “There are all these huge CPG companies in Chicago,” he says. “Those CPG companies are chock full of Millennials … who are, I think, a bit disenchanted with what they do, the companies they work for, and the products they represent. I have interviewed over the past couple of years certainly hundreds of people, and a common theme is, ‘I want to do something that agrees with me not just financially but also emotionally.’”

“I think entrepreneurship is a pretty sexy career these days,” says Lenhardt. “There’s a strong labor force looking to get involved in start-ups.” At Farmer’s Fridge, staff members have degrees from prestigious universities like Northwestern and MIT, and Saunders himself is a graduate of elite Washington University in St. Louis.

Where the Market Is Headed

It’s clear that small companies will continue to play an ever-bigger role in the food industry. Small manufacturers now account for 19% of food and beverage dollar sales, an increase of two percentage points over five years ago, which represents about $2 billion in sales volume, according to recently released Nielsen data (Nielsen 2017). And small companies are driving more than half (53%) of the sales growth, according to Nielsen. It’s clear who is losing ground. Over the same time frame, the largest manufacturers’ share of sales declined from one-third of the market to 31%, Nielsen reports.

Let’s take a look at five young entrepreneurs whose companies are contributing to these shifting market dynamics. Their approaches to market, decisions about funding, educational backgrounds, and business philosophies vary, but they have some commonalities—commitment, persistence, the willingness to ask questions, and of course, big ideas.

Mary Ellen Kuhn is executive editor of Food Technology magazine ([email protected]).

IFTNEXT is made possible through the generous support of Ingredion Incorporated, IFT’s Platinum Innovation Sponsor.

Selling salads in jars from vending machines wasn’t necessarily what Farmer’s Fridge founder and CEO Luke Saunders had in mind when he first started thinking about making healthy food more accessible. It was several years ago, and Saunders, now 31, was working in commercial sales, logging 1,000-plus miles a week driving from one industrial setting to another. He discovered that it wasn’t easy to find something healthy to eat while he was on the road. His travels took him to some large food manuf…

Selling salads in jars from vending machines wasn’t necessarily what Farmer’s Fridge founder and CEO Luke Saunders had in mind when he first started thinking about making healthy food more accessible. It was several years ago, and Saunders, now 31, was working in commercial sales, logging 1,000-plus miles a week driving from one industrial setting to another. He discovered that it wasn’t easy to find something healthy to eat while he was on the road. His travels took him to some large food manuf… Nonetheless, that’s exactly what Saunders wound up doing, installing the first Farmer’s Fridge unit in a food court late in 2013. The company now operates about 75 salad-dispensing vending machines in Chicago office buildings, hospitals, and even O’Hare International Airport and has a staff of 65 people. Expansion into the Milwaukee market is imminent thanks to a recent successful financing round. The company produces the salads fresh daily in a commissary in Chicago and delivers them in refrigerated vans every weekday morning. Each refrigerated unit or “fridge” is stocked with a selection of salads in recyclable jars as well as an assortment of taste-tempting side offerings. Most salads are priced at about $8 and can be ordered via an attractive touchscreen. A recently unveiled app allows salad lovers to check the inventory in nearby fridges if a favorite salad isn’t available at their first stop.

Nonetheless, that’s exactly what Saunders wound up doing, installing the first Farmer’s Fridge unit in a food court late in 2013. The company now operates about 75 salad-dispensing vending machines in Chicago office buildings, hospitals, and even O’Hare International Airport and has a staff of 65 people. Expansion into the Milwaukee market is imminent thanks to a recent successful financing round. The company produces the salads fresh daily in a commissary in Chicago and delivers them in refrigerated vans every weekday morning. Each refrigerated unit or “fridge” is stocked with a selection of salads in recyclable jars as well as an assortment of taste-tempting side offerings. Most salads are priced at about $8 and can be ordered via an attractive touchscreen. A recently unveiled app allows salad lovers to check the inventory in nearby fridges if a favorite salad isn’t available at their first stop. The company adheres to strict cold-chain standards and food safety protocols. “We actually have a PhD food scientist with a background in large CPG companies [on staff],” says Saunders. “He did his PhD thesis on microbe growth in cut lettuce and spinach.” The Farmer’s Fridge software has been designed to ensure that food “auto expires” and cannot be dispensed from a fridge once it reaches that expiration date. Each fridge has a slot where salad purchasers can deposit the salad jars for recycling although many customers elect to keep and reuse them.

The company adheres to strict cold-chain standards and food safety protocols. “We actually have a PhD food scientist with a background in large CPG companies [on staff],” says Saunders. “He did his PhD thesis on microbe growth in cut lettuce and spinach.” The Farmer’s Fridge software has been designed to ensure that food “auto expires” and cannot be dispensed from a fridge once it reaches that expiration date. Each fridge has a slot where salad purchasers can deposit the salad jars for recycling although many customers elect to keep and reuse them. Is the market ready for a sophisticated but expensive portable test kit for consumers with gluten allergies? Shireen Yates and Scott Sundvor, the founders of San Francisco–based start-up Nima Labs are betting that the answer to that question is yes.

Is the market ready for a sophisticated but expensive portable test kit for consumers with gluten allergies? Shireen Yates and Scott Sundvor, the founders of San Francisco–based start-up Nima Labs are betting that the answer to that question is yes. Yates, 33, and Sundvor, 26, met at MIT, where Yates was pursuing her MBA and Sundvor was studying engineering. Both suffered from food allergies and sensitivities and were intrigued by the idea of trying to build a company that would address the diges…

Yates, 33, and Sundvor, 26, met at MIT, where Yates was pursuing her MBA and Sundvor was studying engineering. Both suffered from food allergies and sensitivities and were intrigued by the idea of trying to build a company that would address the diges… The system is pricey—$279 for a starter kit that includes three test capsules, but a close-up look at the proprietary science and engineering technology that went into developing it helps to explain the price point. The system is built around a pair of highly specific and sensitive gluten-detecting antibodies developed by the Nima team. Each Nima capsule includes a test strip preloaded with the antibodies. When gluten is detected in food that the test kit user inserts into the capsule, antibodies on the strip bind to the gluten proteins and deliver a signal change on the strip. A sensor detects that signal and delivers the results in a consumer-friendly way; a wheat symbol appears if gluten has been detected, and a smiley face means that the food sample contains less than 20 ppm gluten. It all happens in about three minutes or less.

The system is pricey—$279 for a starter kit that includes three test capsules, but a close-up look at the proprietary science and engineering technology that went into developing it helps to explain the price point. The system is built around a pair of highly specific and sensitive gluten-detecting antibodies developed by the Nima team. Each Nima capsule includes a test strip preloaded with the antibodies. When gluten is detected in food that the test kit user inserts into the capsule, antibodies on the strip bind to the gluten proteins and deliver a signal change on the strip. A sensor detects that signal and delivers the results in a consumer-friendly way; a wheat symbol appears if gluten has been detected, and a smiley face means that the food sample contains less than 20 ppm gluten. It all happens in about three minutes or less.

Although PRE’s value-added products appeal to the kinds of consumers who shop in the natural products and specialty channels, Lebovich and his executive team opted not to go that route, focusing instead on mainstream retailers. “We chose to go after where we thought the majority of consumers would be, and we chose to go where we thought we could deliver a more attractive price to a larger part of the market,” he says.

Although PRE’s value-added products appeal to the kinds of consumers who shop in the natural products and specialty channels, Lebovich and his executive team opted not to go that route, focusing instead on mainstream retailers. “We chose to go after where we thought the majority of consumers would be, and we chose to go where we thought we could deliver a more attractive price to a larger part of the market,” he says.

Her goal was to formulate a versatile, natural sauce that helps “people get a really satisfying dinner on the table easier, faster, and happier.” The Jar Goods assortment currently includes Classic Spicy, Classic Red, and Classic Vodka varieties with additions to the lineup, including a Vegan Vodka tomato sauce, a Black Tapenade, and a Purple Pesto sauce, planned for later this year.

Her goal was to formulate a versatile, natural sauce that helps “people get a really satisfying dinner on the table easier, faster, and happier.” The Jar Goods assortment currently includes Classic Spicy, Classic Red, and Classic Vodka varieties with additions to the lineup, including a Vegan Vodka tomato sauce, a Black Tapenade, and a Purple Pesto sauce, planned for later this year. For most entrepreneurs, long hours come with the territory, leaving all too little time to focus on the rest of life. Dan Staackmann, founder and CEO of Chicago-based vegan foods maker Upton’s Naturals, has found a way to help solve that common entrepreneurial dilemma. A few years back, he had a combined factory/ office/residence built, and now he lives right above his office.

For most entrepreneurs, long hours come with the territory, leaving all too little time to focus on the rest of life. Dan Staackmann, founder and CEO of Chicago-based vegan foods maker Upton’s Naturals, has found a way to help solve that common entrepreneurial dilemma. A few years back, he had a combined factory/ office/residence built, and now he lives right above his office. A longtime “ethical vegan,” Staackmann, 40, decided to venture into the food business when he realized that there weren’t a lot of companies producing one of his favorite products, the wheat-based meat alternative seitan. Staackmann spent some time tinkering with product formulations before rolling out Upton’s Naturals seitan in 2006. Funding the start-up with a home equity line of credit and working in shared kitchen space, “We did all the build-out for under $40,000 and then approached Whole Foods,” says Staackmann. “We were able to get placement in seven stores and once those did well, we got into 20 in the greater Chicago area.” Within six months, Upton’s had distribution in all Whole Foods Market’s Midwest region stores and eventually reached national distribution in Whole Foods.

A longtime “ethical vegan,” Staackmann, 40, decided to venture into the food business when he realized that there weren’t a lot of companies producing one of his favorite products, the wheat-based meat alternative seitan. Staackmann spent some time tinkering with product formulations before rolling out Upton’s Naturals seitan in 2006. Funding the start-up with a home equity line of credit and working in shared kitchen space, “We did all the build-out for under $40,000 and then approached Whole Foods,” says Staackmann. “We were able to get placement in seven stores and once those did well, we got into 20 in the greater Chicago area.” Within six months, Upton’s had distribution in all Whole Foods Market’s Midwest region stores and eventually reached national distribution in Whole Foods.