Consumer Perceptions of ‘Natural’ Foods

A recent study of primary grocery shoppers in the United States provides insights on what the term natural means to consumers and its association with food processing techniques.

Article Content

Consumers appear to prefer “natural” foods, and yet there is little consensus on what, precisely, the term means. Food companies are allowed to use a natural label or claim, but the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has refrained from defining the term. One consequence has been a number of lawsuits in recent years in which plaintiffs claim to suffer harm from being misled about food product contents or ingredients when accompanied with a natural label (Creswell 2018). In 2015, the FDA requested public comment on the use of the term natural in food labeling, and in 2018, the FDA commissioner indicated intentions to define the term (Bloch 2018). Such events suggest the need for more information about how food consumers perceive and define the term natural.

Prior research shows that natural labels influence consumer choice and that consumers are willing to pay premiums for natural labels (e.g., Asioli et al. 2017, Lusk 2019); however, research also shows that consumers are sometimes misled by such claims. For example, Syrengelas et al. (2018) showed that consumers were willing to pay significant premiums for meat products labeled natural, a figure that fell to zero when consumers were informed of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s definition of the term on meat products, which is primarily that the product is minimally processed.

Surveying U.S. Grocery Shoppers

A nationwide, online survey of U.S. food consumers was fielded in December 2018. The survey was written and programmed by the author and was administered to an online panel maintained by Survey Sampling International. The first question on the survey asked how much of the grocery shopping the respondent did for their household. Anyone who provided an answer indicating that they were responsible for less than half their household’s grocery shopping was immediately directed to the end of the survey and were excluded from this analysis. Moreover, for quality control, two “trap” questions were included in the survey, which asked respondents to choose a specific answer (e.g., “somewhat agree”) if they were paying attention. Respondents who missed either of the trap questions were also excluded from the analysis. Lastly, as a further quality control measure, responses to three open-ended questions were inspected, and respondents who provided non-sensical answers (e.g., “asdkf”) were removed from the sample.

After applying the aforementioned exclusionary criteria, the final sample consists of 1,290 respondents, which yields a sampling error of 2.7%. Responses were weighted to match the U.S. population in terms of region of residence in the U.S., age, education, and gender.

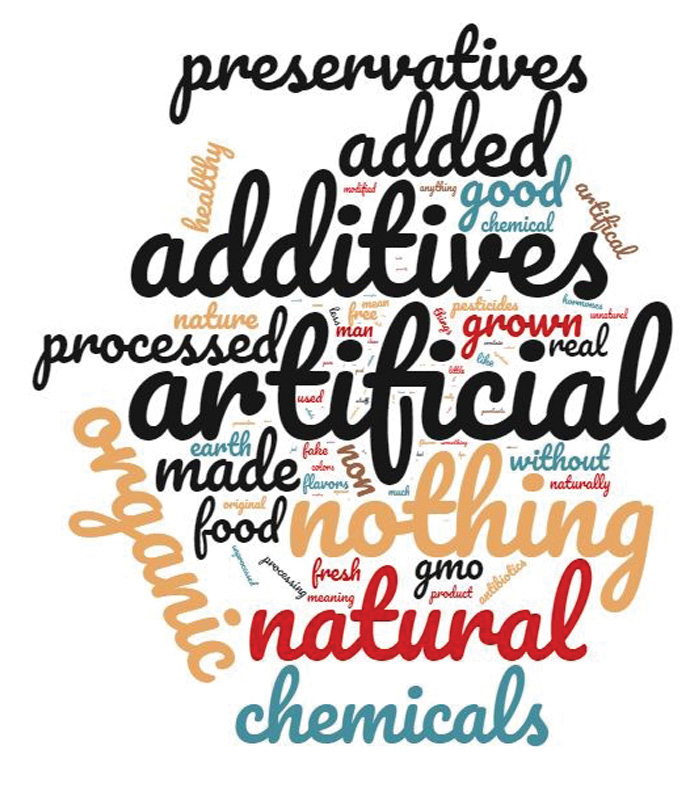

This article focuses on consumers’ responses to three definitional questions, one open-ended and the other two guided, related to their perceptions of the term natural, in addition to asking some questions about policy preferences. Respondents were asked an open-ended question, “What does it mean to you for a food to be called ‘natural’? (please type one or two words in the blank below).” Responses to the open-ended question were used to create a word cloud illustrating the relative frequency with which different words were mentioned by respondents. In creation of the word cloud, commonly mentioned non-descript words like “food” and “ingredient” were removed, as were words such as “an,” “the,” “or,” “means,” etc. Words mentioned fewer than five times were also removed.

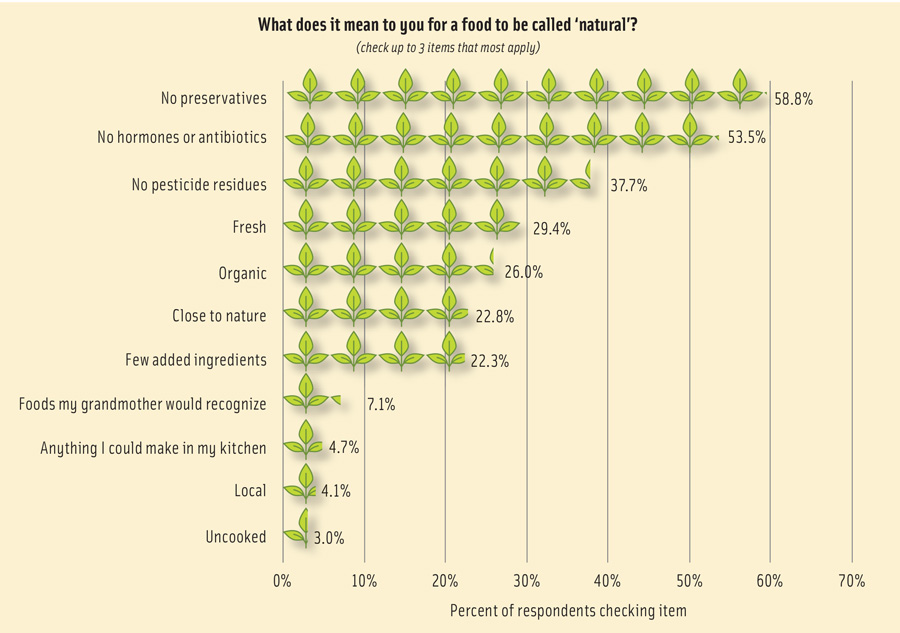

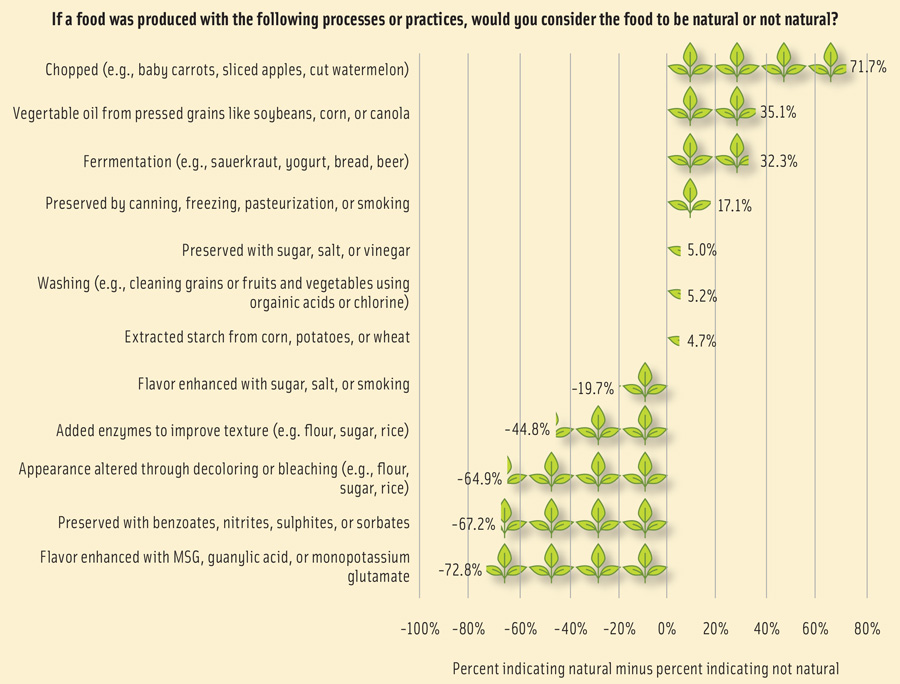

The question was followed by a guided query, and consumers were provided a list of 11 possible definitions and were asked which most applied to the meaning of the word natural. Respondents were also provided a list of 12 food processes in random order and were asked to indicate whether each was natural, not natural, or neither natural nor not natural. For each item, a naturalness score was created by subtracting the percent of respondents who considered a process not natural from the percent of respondents who considered a process natural. For both these questions, rather than asking “choose all that apply”, respondents were asked to “choose the three items that most apply” so as to force respondents to prioritize their responses and to induce more careful consideration.

What Shoppers Had To Say

Figure 1 shows a word cloud constructed from responses to the open-ended question. When asked what it meant to respondents for a food to be called natural, words like artificial, additive, chemical, and organic were most commonly mentioned. More than 10% of respondents specifically mentioned the word artificial, and 9% mentioned “additive.” “Organic” was mentioned by 7% of respondents, followed by “added” (6.5%), and “processed” (5.6%). “GMO” or “genetic” was only mentioned by 3% of respondents. A non-trivial share of respondents suggested the word was meaningless, marketing hype, or that they did not know what the word meant (8.7% said the word meant “nothing”). Many respondents provided tautological-like definitions, for example using the word “natural” to define “natural.”

Following the open-ended question of the meaning of natural, respondents were provided with a list of 11 possible definitions and were asked which most applied to the meaning of the word natural. Figure 2 shows that more than half of respondents indicated a food was natural if it had “no preservatives” and “no hormones and antibiotics.” Almost 40% of respondents said “no pesticide residues” was natural. Only 29.4% said “fresh” was indicative of natural, slightly more than the 26% who said the same of organic. Only 22.3% said a food needed “few added ingredients” to be natural, and only 7.1% said only “foods my grandmother would recognize” are natural. Consumers do not seem to associate cooking or localness to relate to naturalness as much as the other items in the list.

Figure 3 shows perceptions of the naturalness of different food processes. Nearly 77% of respondents indicated “chopped” was natural, whereas only 5.3% thought this process was not natural, implying 71.7% (76.9% minus 5.3% equals 71.7%) thought chopping was more natural than not. Thirty percent more respondents thought fermentation and pressing to create vegetable oil was natural as compared to the percentage who found these processes not natural. Preservation by canning and with sugar/salt/vinegar were perceived as net-natural, whereas preservation with benzoates/nitrites/sulfites was not. That “washing” had an only moderately net positive natural score is likely explained by the parenthetical definition provided, which indicated, “(e.g., cleaning grains or fruits and vegetables using organic acids or chlorine).”

After several additional questions about natural foods, respondents were asked about their preferences for the regulation of natural labels on food. Respondents were asked, “How do you believe natural labels should be regulated.” Three options were provided: 1) The FDA should regulate to prevent the use of the term “natural” on food packages, 2) The FDA should not regulate the use of the term “natural” on food packages, and 3) The FDA should regulate the use of the term “natural” by requiring companies to follow a uniform, consistent definition. Almost two-thirds of consumers picked the last option. A little over 20% of respondents thought the FDA should prohibit the use of natural labels.

Despite this policy preference, less than half of respondents (44.4%) indicated that they either highly or somewhat highly trust the FDA to define the term in a way that they would find useful in making food choices. A third of respondents said they neither trust nor distrust the FDA to undertake this task.

Just because a federal definition of natural exists does not mean consumers know or understand the definition. Responses to the following question illustrate this point. Respondents were asked, “The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) regulates the use of the label ‘natural’ for meat.” Which of the following best matches the current USDA definition for ‘natural’ meat?” Respondents picked one of five options: cage free, grass fed, no antibiotics, minimally processed, or no hormones. In actuality, the USDA primarily defines the term on meat as implying “minimally processed.” However, only about a quarter of respondents (26.6%) correctly picked this definition. More than 30% of respondents incorrectly believed the USDA definition of natural implies “no hormones” and 23.8% thought a natural label implies “no antibiotics.” These data suggest more than half of respondents are misled by the USDA definition of natural, a result supported by the findings of Syrengelas et al. (2018).

Key Takeaways

The FDA has signaled interest in defining the term “natural” on food labels, and as such, insights into how consumers define and interpret these terms is needed. Overall, results suggest nuanced, and sometimes logically inconsistent, views about the meaning of natural. Several lines of evidence reveal that consumers do not perceive “naturalness” as a single unifying construct, but rather a food or process can be seen to be high in one dimension of naturalness but low in another dimension of naturalness.

When unaided, consumers were most likely to associate the meaning of natural food with words like artificial, additive, chemical, and organic. When provided with different response categories, more than half of respondents indicated a food was natural if it had “no preservatives” and “no hormones and antibiotics.” Almost 40% of respondents said “no pesticide residues” was natural. These responses were much more common than beliefs that fresh, uncooked, few added ingredients, or localness implied naturalness.

Despite the general belief that natural implies “no preservatives,” when specifically asked about particular types of preservatives, more respondents than not thought various processes like fermentation, canning and smoking or preservation ingredients like salt, sugar, or vinegar were natural. Artificial- or chemical-sounding preservatives like benzoates, nitrites, and sulfites were considered by more consumers to be unnatural than natural.

Consumers largely support the FDA efforts to regulate the term natural. However, despite this policy preference, less than half of respondents said they trusted the FDA to define the term in a way that they would find useful in making food choices. Moreover, analysis of consumers’ understanding of USDA’s definition of natural meat products provides a cautionary tale. In particular, just because a federal definition of natural exists does not mean consumers know or understand the definition. Only about a quarter of respondents correctly knew the USDA definition for meat, and more than half incorrectly believed the USDA definition of natural implies “no hormones” or “no antibiotics.” Such findings suggest the possibility for consumers to be misled by natural labels, even if defined by the FDA, and suggest the need for whatever definition is adopted to accompany natural claims.

Jayson L. Lusk, PhD, is a distinguished professor and head of the agricultural economics department at Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN ([email protected]).

Acknowledgements

The survey was funded by the Corn Refiners Association, but the choice of questions asked and the analysis conducted were solely at the discretion of the author, and the discussion and opinions reported herein only reflect the views of the author and not the Corn Refiners Association.

Food Technology Articles

How to Formulate for Food Intolerances

In this column, the author describes the global prevalence of food intolerances and provides insight into state-of-science ingredient replacement and removal methods when formulating gluten-free and lactose-free foods.

Vickie Kloeris Shares NASA Experiences in New Book, Consumers Are Confused About Processed Foods’ Definition

Innovations, research, and insights in food science, product development, and consumer trends.

Top 10 Functional Food Trends: Reinventing Wellness

Consumer health challenges, mounting interest in food as medicine, and the blurring line between foods and supplements will spawn functional food and beverage opportunities.

Better-for-you products on display at Natural Products Expo West

A photo overview of products shared at the 2024 Natural Products Expo West in Anaheim, Calif.

Adapting to Change: Insights From the RCA Conference

An overview of insights shared at the Research Chefs Association (RCA) Annual Conference & Culinology Expo in Quincy, Mass.

IFT Podcasts

EP 11: The Challenge of Water

Water is a critical resource for growing and processing food. This episode discusses the challenges we face regarding water, and present and future solutions to resolve them.

EP 4: Consumers Don’t Want to Change, So Why Are They

With up to 40,000 products in a grocery store, many consumers are on auto-pilot when deciding what products to buy.