The Dawn of the Food Packaging Value Chain

PACKAGING

Since trading of packaged foods began, various types of supply chain management and logistics have orchestrated the flow of packaged foods from one location to another. Data-based technologies and supply management initiatives such as vendor-managed inventories, efficient consumer response, third-party logistics, and just-in-time enabled a global revolution in how and where consumers obtain packaged foods. The recent food crisis and the global financial crisis of 2008–2009 demonstrated that a value chain approach to focus on the consumer value of packaged food is essential to complement food supply chain management. Supply chain logistics have been augmented by the value chain, which pulls through consumer and market demands. The food packaging value chain is led by the consumer; hence the consumer-defined value of packaged food is transferred in the value chain. In contrast, the food supply chain is led by supply and defines packaged food logistics from suppliers to consumers.

The packaged food value chain age has become the means through which the packaging industry navigates to achieve goals. Value chain thinking has evolved from a linear model to a more circular integrated model that aligns supply chain entities with the common thread of bringing specific value to consumers. This model fine-tunes the value that each entity in the value chain transfers to the next entity to achieve specific consumer value in a manner similar to quality function deployment. The rationale for the value chain is clear from a consumer view because consumers value some packaged foods more than others. The value chain is a means to create packaged food that is valued more by consumers.

Value Chain Relationships

The relationships between the supply chain entities and an expanded network that has common priorities, measurement systems, and activities are the core of the value chain. These relationships are built, fostered, and continually enhanced to ensure the focus is on the consumer by managing knowledge, creating joint value with shared work, and rewarding significance in relationships. Notably, significance-based reward systems in the value chain differ from more traditional rewards. The main objective of reward systems in the packaging value chain is to reward the value transferred. For example, in food packaging, many open–reclose features malfunction, resulting in consumer frustration. When value chain concepts are applied, the paramount value of the consumer’s ability to successfully use the open–reclose feature is transferred down the value chain, and the knowledge, shared work, and reward systems are aligned to ensure the successful operation of this feature. An example of employing value chain process thinking and significance-based reward systems is taking action following a decrease in consumer complaints to implement reward systems for all employees in the entire value chain—from packaging suppliers and converters to retailers (Sand 2010). In this example, the rewards included paid vacation and funds for childcare, which were meaningful to employees. Reward systems in companies with reliable packaging value chains are agile and adjust to each type of achievement. Understanding what is essential to consumers becomes systemic and ensures that company goals and activities align with customers’ customers, and eventually, the consumer at the front of the value chain.

Innovation and the Value Chain

Innovation partners need joint development agreements and nondisclosure agreements to protect intellectual property. However, using value chain thinking for innovation requires the transfer of tacit social vs. explicit knowledge. This knowledge is essential to transfer value. Value creation networks or clusters focus on a low transaction cost of tacit social knowledge and thus achieve a high degree of innovation. Interestingly, they have evolved from the geographic-based cluster into a more virtual network. Common core competencies are developed within the cluster and competency-based innovation ability rises. Clusters vary based on consumer needs. For example, entrepreneurial packaged food–focused clusters are aligned to have the competitive advantage of agility in ingredient and package changes and rapid scale-up, providing unique food product and package consumer experiences. However, established food company cluster alignment and social tacit knowledge transfer focuses on innovations in efficiency, cost savings, and achieving national launches.

An example of innovation clusters focusing on the consumer relates to response to the rapid increase in flexible packaging that is now discarded by consumers purchasing food online. The closed-loop recycling that retailers use for secondary and tertiary packaging is missing in the altered value chain for consumers who order food online; and the flexible packaging is not collected or recycled from consumers in the United States. Two value chain approaches to this issue are being explored. The first approach eliminates consumer handling of flexible packaging. This material and machinery innovation from value chain–oriented packaging suppliers and machinery companies, such as Renova, KHG Group, Sofidel, and Paper Converting Machine Company (of Barry-Wehmiller), replaces flexible packaging with paper in retail stores and for products shipped to consumers. The second approach by value chain–oriented material recycling facilities and retailers is to refine the collection and sorting of flexible packaging to enable consumers to recycle the packaging. Importantly, changes in the value chain are needed to accommodate the handling of paper-based secondary and tertiary packaging and altered recycling systems. Companies are joining efforts, creating shared value, and using solution clusters to identify and address gaps in the framework to meet consumer needs.

Society and the Value Chain

The value chain plays a role in fostering economically, socially, and environmentally responsible practices because value chains are confident in their ability to make a positive impact on consumers and society. How well a company connects with consumers using the value chain is reflective of their corporate responsibility or shared value (Kroupová 2015). For example, in regions where industry-derived pollution is rampant, there is a value chain disconnect between the shared value possible between industry and the adjacent population, some of whom are consumers. When consumers demand a lower environmental footprint, traceability, and a consistent supply of packaged food, this translates down the value chain to packaging suppliers in the form of confidence in the package material chain of custody, agility, and effective disaster and energy management. The value chain approach to sustainability requires consideration of the environmental impact of the entire food system versus isolated segments (Verghese et al. 2016). The business ethics of social entrepreneurs who profit by making a positive environmental and community impact are driving more tangible improvements within the food industry. For example, consumers may not experience environmental impact of manufacturing packaging for all food packaging they use due to the expanded global packaging supply chain. Actual tangible data on this environmental impact helps consumers make more informed purchase decisions. The capacity of global value chains to work within a shared value context has been questioned because the value chain is complex; however, this is essential to lessen the environmental impact of packaged food on the world as a whole.

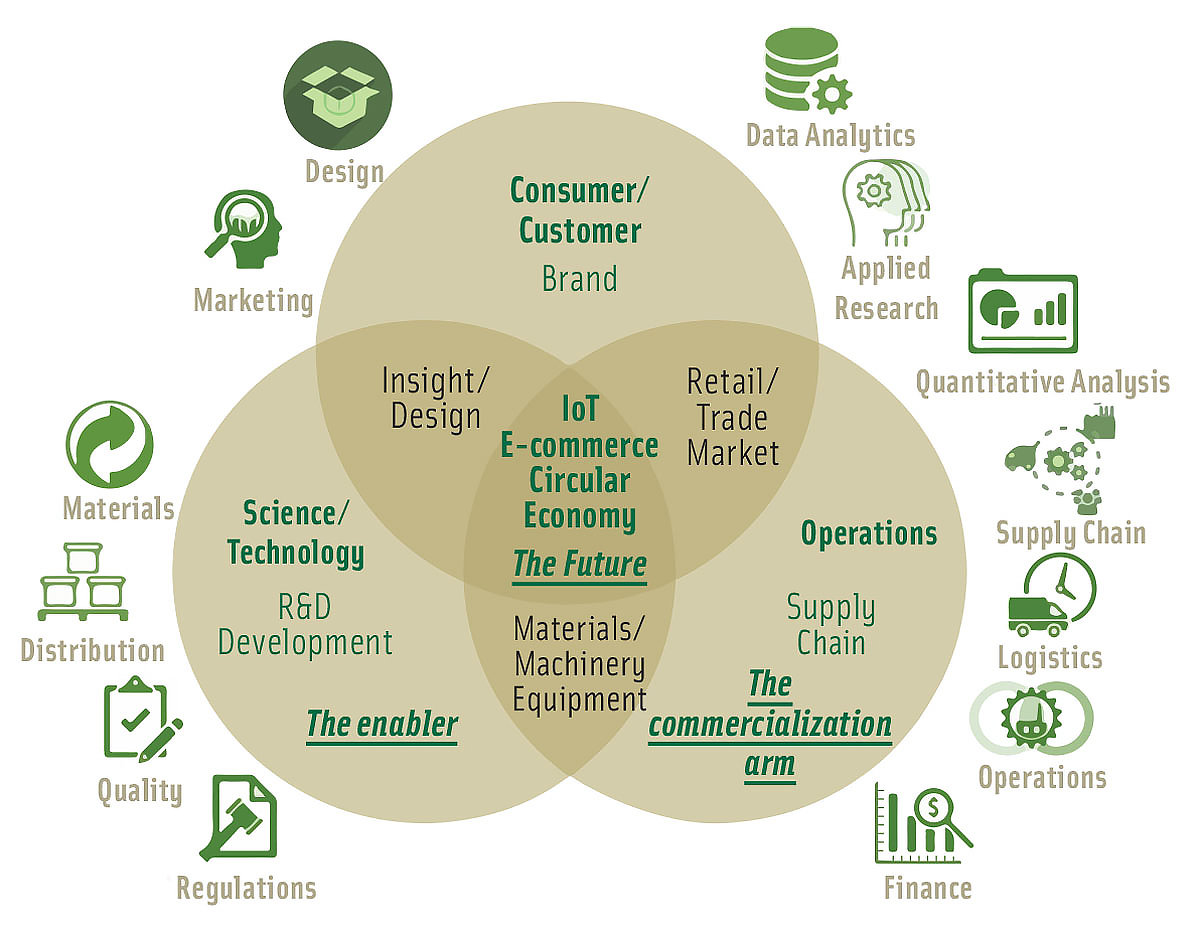

Notably, universities are advancing the packaging value chain thinking by augmenting supply chain management and packaging science coursework with value chain concepts at the undergraduate and graduate levels and for certificate-seeking students. For example, Michigan State University has a value chain management undergraduate track. Other universities, such as Rochester Institute of Technology and Clemson University have coursework in or related to the packaging value chain. California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo (Cal Poly) offers its undergraduates two unique amalgamations of packaging value chain related disciplines, a concentration in consumer packaging to business administration majors, and a packaging technology concentration to its industrial technology and packaging majors. Since its inception in 2018, the Cal Poly packaging value chain MS program has grown to include courses taught by four multidisciplinary faculty and three industry leaders in finance, industrial technology, the legal profession, graphic communications, analytics, and manufacturing, which augments the courses taught by five packaging faculty members. Jay Singh, professor and packaging program director at the Orfalea College of Business at Cal Poly explains: “Packaging value chain courses at universities help professionals create efficient and effective packaging solutions using packaging science and technology, data analytics, marketing, finance, supply chain management, operations, and quantitative analysis. By purposefully connecting each course within the Cal Poly program, we create a complexity of knowledge that our working students can readily apply to their careers.” Packaging value chain research related to food preservation is also becoming more established. For example, Cal Poly’s Packaging Research Consortium and its annual FreshPACKMoves Forum have been offering its members and participants the critical edge in the competitive arenas of packaging innovation, food safety and traceability, and cold-chain logistics for fresh perishables.

REFERENCES

Kroupová, Z. 2015. “Shared Value and Its Regional and Industrial Reflection in Corporate Projects.” Cent. Eur. Bus. Rev. 4 (3): 13-22.

Sand, C. 2010. The Packaging Value Chain. Lancaster, Pennsylvania: DesTech Publishing.

Verghese K., H. Lewis, S. Lockrey, et al. 2016. “Packaging’s Role in Minimizing Food Loss and Waste Across the Supply Chain Packaging Technology and Science.” Packag. Technol. Sci. 28(7): 603-620. https://doi.org/10.1002/pts.2127.