Addressing a Viral Threat

As the coronavirus exacts its brutal toll on human health around the globe, the food system has responded with heroic efforts to safely manufacture, distribute, and sell food.

Article Content

The world changed early this year when the novel coronavirus began its invasive move beyond China where it surfaced late in 2019, prompting the World Health Organization to declare an international public health emergency by the end of January. Its impact on the food system was swift and dramatic: panicked shoppers, unprecedented retail shortages, an overstressed supply chain, and food manufacturers challenged to meet surging demand while keeping their employees safe. Here’s a look at how the food industry has responded and what it is likely to mean for key segments going forward.

Foodservice Fallout

Foodservice operators were among the first to feel the true impact of the COVID-19 crisis. As the pandemic spread across the United States between mid and late March, states began to issue stay-at-home orders and require restaurants to forgo dine-in services. Many independent restaurants closed while other quick-service and fast-food restaurants shifted to offering only drive-thru, takeout, or delivery services.

“With more than 97% of the nation’s 660,000 restaurants being restricted to off-premise only sales, the single biggest challenge if you’re traditionally an on-premise, full-service restaurant, is being able to pivot to an off-premise model,” explains David Portalatin, vice president, industry advisor – food, The NPD Group. “But obviously for some restaurants, like quick-service restaurants, whose business is heavily toward the takeout side of the business, that’s been a little bit easier to do. But even for quick-service restaurants through the weekend ending March 29, the transactions were down 40% year over year.”

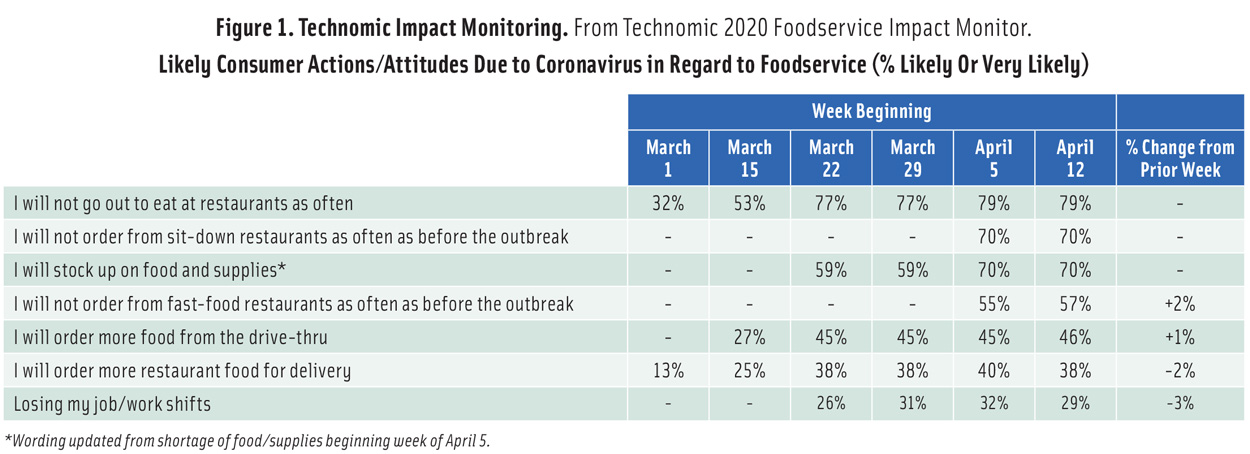

This is still considerably better than full-service restaurants, whose transactions for the week ending March 29 were down 79% compared with the same week a year ago (NPD 2020). This reflects not only the challenges in launching or ramping up delivery and takeout models, but also consumer fear surrounding the safety of eating food not prepared at home. According to Technomic’s survey of U.S. consumers for the week beginning April 12, 79% responded that they “will not go out to eat at restaurants as often” due to the coronavirus (Figure 1).

In addition, as the economy plunges into a recession and with more than 16 million people losing their jobs in just three weeks (as of April 4), the discretionary spending on takeout and delivery is likely to suffer (U.S. Dept. of Labor 2020). Even the fast-food giant McDonald’s is struggling. In a report filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission on April 8, McDonald’s reported that comparable global sales for the two months that ended Feb. 29, 2020, increased 7.2%. However, the company reported a global sales decrease of 22.2% for the month ending March 31, 2020.

“We certainly expect chains to be able to withstand this loss of revenue for longer than independent operators will be able to,” says Portalatin, who explains that of 660,000 U.S. restaurants, 360,000 of them are one- or two-store operations. According to Datassential, 44% of fine-dining, 36% of casual-dining, 24% of midscale, 13% of fast-casual, and 10% of quick-service restaurants have temporarily shuttered, many hoping to have enough to pay rent until the pandemic ends (2020).

“Businesses need to boil down the truly unique experience qualities that they are selling and focus on how to do that remotely or with new services, products, etc.,” advises Maeve Webster, president of consultancy Menu Matters. The three Michelin star Chicago restaurant Alinea is known for its pricey and elaborate tasting menus, but the pandemic meant it couldn’t offer the same dine-in service that has kept it in business since 2005. Instead of remaining closed, Alinea Group decided to use Tock—its reservation, table, and event management system—to enable customers to reserve a to-go meal for curbside pickup. As a replacement for its multicourse meal ending with an edible helium balloon made from green apple taffy, guests can order coq au vin, with a side of 50-50 mashed potatoes, and salad dressed in mustard vinaigrette with a dark chocolate pot de crème for dessert. It’s comfort food at a price of $39.95 per person.

While the change is likely to garner Alinea increased media coverage and new fans, it is unlikely to bring in the revenue that the restaurant regularly generated pre-pandemic. This is going to be the case for most foodservice establishments. According to Datassential, 86% of operators as of March 27 have experienced some increase in takeout but not enough to offset dine-in losses (2020).

To cut overhead, most restaurants have had to furlough or lay off staff, streamline their menus, and enter new dayparts, all while trying to attract wary customers. “There are all kinds of interesting ways that I think restaurants are trying to be relevant to consumers,” says Portalatin. “We’re seeing menus be streamlined and only offering those items that are conducive to very rapid production with maybe minimal staff, and those foods that are conducive to being transported and still hold their quality for a delivery or takeout order.

“Technology certainly plays a role,” Portalatin continues. “For example, for most restaurants, even if all their customers wanted to order for takeout, they don’t have either the digital apps, the website, or the telephone systems to handle that volume of orders.” That’s why many restaurants are turning to third-party delivery companies to enable them to quickly adapt to the new normal.

Recognizing that delivery is vital to its survival, Shake Shack expanded its partnerships with delivery providers. “In addition to our focus on the pre-ordering convenience of our Shack app and web channels, we are taking this moment to add additional delivery partners to all Shacks where available,” says Randy Garutti, CEO of Shake Shack, in a company press release. The chain now offers delivery via Postmates, DoorDash, Caviar, Uber Eats, and Grubhub. According to The New York Times, on one day in March, Grubhub added more than four times as many restaurants to its app as it had on its previous record day (Yaffe-Bellany 2020).

Since the pandemic began, Scott Landers, who runs food delivery consulting group Figure Eight Logistics, has started offering free consulting sessions to owners who are trying to improve their delivery operations. “Any successful off-premises experience must consider a few things,” explains Landers. Price, packaging, and product are key. Many food delivery companies have waived their delivery fee for customers, helping to mitigate the price barrier for delivery.

Soon after the pandemic began, most of the third-party delivery companies introduced contact-free delivery where there’s no physical interaction between delivery personnel and customers. This, in combination with the waiving of delivery fees, has helped some hesitant consumers make the switch to delivery, but in many cases, the operators are still paying commission fees ranging from 10% to 30% on every order.

The National Restaurant Association stated in a press release on April 9 that 15% of restaurants had already permanently closed or would do so within two weeks. In its efforts to appeal to the U.S. Congress for more relief funds, the association pointed out that the pandemic has “already cost three million restaurant employees their jobs and cut $25 billion in revenue from the industry since March 1.”

“The vast majority of independent restaurants that closed won’t come back,” predicts Webster of Menu Matters.

Grocery Retail: March Madness

Data and analytics provider IRI pegged the start of panic buying in the United States to the weekend of February 28 to March 1, when the first U.S. death from COVID-19 occurred. As U.S. consumers became more aware of its potentially lethal impact, national hysteria meant that the stock-up pattern was widespread, according to alternative data provider M Science, which reports that sales surged across the country, independent of the number of local incidences of COVID-19. After the

initial shopping surge, consumers continued to stock up as the month progressed but soon began making fewer, larger shopping trips as social distancing practices increased, says Joan Driggs, IRI vice president, content and thought leadership. Dollar stores, Costco, and Walmart showed some of the largest year-over-year growth in the early days of the crisis, M Science reports.

Supermarket retailers have plenty of experience dealing with shopping spikes triggered by hurricanes, earthquakes, and other natural disasters, but the coronavirus crisis had an unprecedented impact, says Doug Baker, vice president, industry relations, for FMI-The Food Industry Association. “Crises are nothing new to these folks,” says Baker. “[But] compared to a natural disaster, it was comparable for the first five hours, and then it became incomparable. Things were just moving so quickly and changed so dramatically.”

Faced with unprecedented shopper demand, retailers scrambled to keep products in stock and on store shelves while dealing with supply chain challenges and the need to quickly ramp up staffing. Many focused hiring efforts on foodservice and hotel industry employees who had lost their jobs as a result of the pandemic. Grocery retailer Albertsons, for example, announced in late March that it was hiring 30,000 new associates and quickly forged partnerships with Hilton, Marriott, MGM Resorts, and other hospitality industry companies (Albertsons 2020). To help retailers cope, FMI instituted daily calls in which retailers shared their experiences with one another, which has allowed the industry to start developing best practices on everything from enhanced sanitation initiatives to designated times for seniors to shop. M Science reports that by mid-March large supermarket chains were showing the strongest sales growth, outperforming natural/organic specialty retailers. M Science analysts theorize that the supermarkets’ larger footprints appealed to consumers seeking to minimize both the number of their trips to the store as well as their contact with others inside the store.

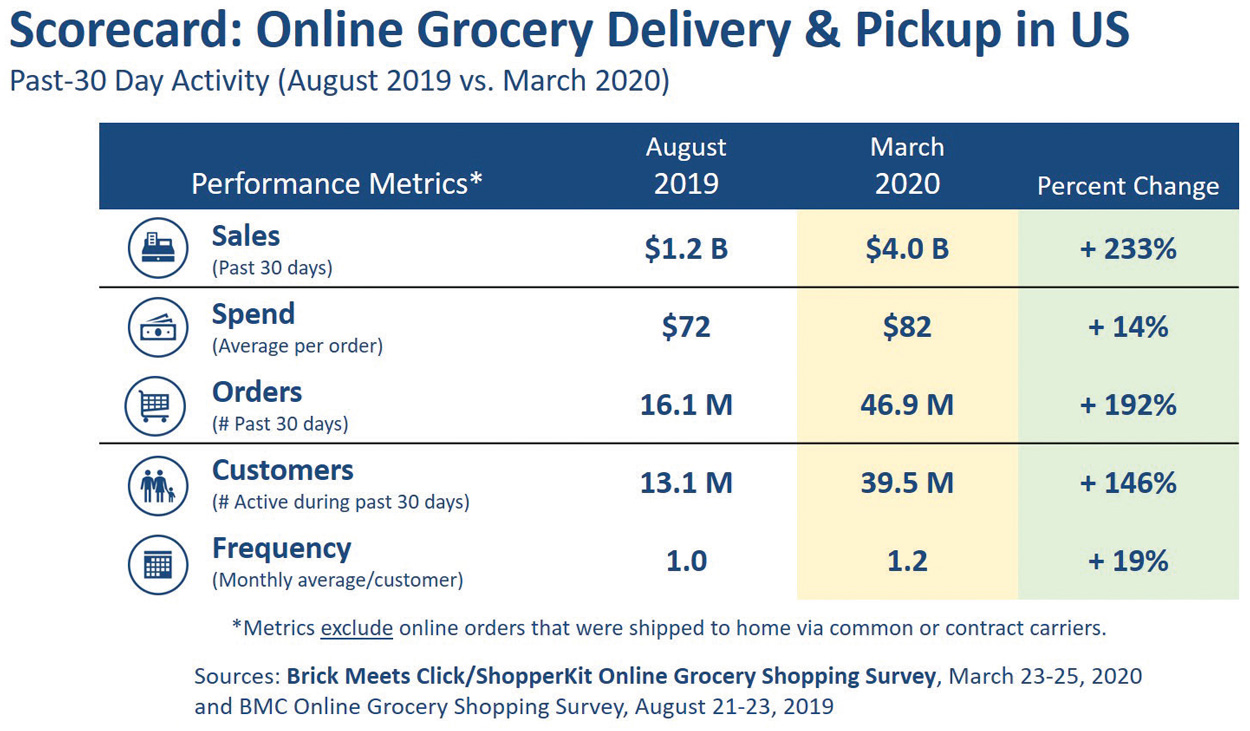

Unsurprisingly, as the virus spread, more consumers turned to e-commerce options. Research by consulting company Brick Meets Click found that 31% of U.S. households ordered groceries online for home delivery or pickup at the store in the month of March compared with only about 13% who did so in August 2019 (Brick Meets Click 2020). Sales of groceries ordered online for delivery or pickup surged 233% in March versus August, adds David Bishop, Brick Meets Click partner (Figure 2).

The experience wasn’t always seamless, however. Repeat purchase intent dropped from 74% in August to 43% in March, which Bishop attributes to the fact that many shoppers were unable to buy the products they wanted, faced long delivery delays, and often didn’t have the ability to select a time slot for delivery. “What this means is that more of the online shoppers are in play as they’ll most likely try another service during the crisis to assess how acceptable an alternative it is to shopping elsewhere online or even in the store,” says Bishop.

Food Companies Step Up

Pandemic food hoarding started with canned goods, then moved to frozen vegetables, frozen meals, bottled water, and shelf-stable products. “My estimate is that food-at-home spending has increased to 80% of dollars spent on food compared to 47% normally,” says Robert Moskow, a research analyst at Credit Suisse. “That translates into like a 66% increase in dollars spent at grocery stores. And you can see it in the retail data today. Conagra said that over the past two weeks [end of March], their sales are up 100%.”

In their March report, Credit Suisse analysts called out Campbell, Conagra, and Smucker as among the companies they predict will benefit the most from consumers’ abrupt transition to sheltering in place. Another packaged food giant, Kraft Heinz, which had its debt rating downgraded by Fitch Ratings to “BB+” from “BBB-” in February, has seen a bump in sales with the stockpiling of packaged foods. “The company’s growth has accelerated in the wake of very strong consumer demand for its products and trusted brands, despite significant declines in foodservice-related sales around the world,” wrote the company in a press release on April 6. “Net sales are now expected to increase approximately 3%, and organic net sales are expected to increase approximately 6%.”

In an environment where everyone is consuming all meals at home, easy-to-prepare foods like canned soup, frozen vegetables, and spreads became hot commodities. And the longer that the stay-at-home orders last, the more shelf-stable foods Americans are buying.

“At-home consumption patterns are probably going to be up 15% to 25% even after the pantry loading is over,” predicts Moskow. “It will last while we’re in this unusual period where offices are closed, schools are closed … so, I’m forecasting that out 90 days.

“I think that anything having to do with cooking at home and recipes—McCormick, for example—might see a benefit [during the pandemic], although there’s offsets there because they have a big foodservice division,” continues Moskow. “I think Conagra’s frozen vegetable business will have a huge benefit.”

To meet this surge in demand for packaged foods, manufacturers have been working—literally around the clock—to ramp up production and keep grocery store shelves stocked. “The fact that food workers have been designated as essential signifies the responsibility of the food industry to keep the supply of food constant,” says TC Chatterjee, CEO of Griffith Foods, a family-owned global product development partner specializing in healthy, nutritious, and sustainably created ingredients.

While demand for retail foods and beverages has soared, manufacturers supplying foodservice operators saw demand plummet as restaurants, movie theaters, and arenas were mandated to close to prevent the spread of COVID-19. According to a Reuters article, Kraft Heinz made the move to significantly reduce production at three of its plants that provide restaurant supplies and has added shifts at other facilities to meet the demand for its packaged foods like macaroni and cheese (Mandl 2020).

Companies like J & J Snack Foods that sell primarily to foodservice accounts have been hard hit. The company, which makes SuperPretzel, Luigi’s Real Italian Ice, and frozen beverage brands ICEE and Slush Puppie, revised its outlook on March 22, anticipating that the impact of the coronavirus crisis will be “decidedly negative” given that “two-thirds of its annual revenue of approximately $1.2 billion is to venues and locations that have shut down or sharply curtailed their foodservice operations over the past 10 days.”

Shifting production from foodservice to retail is not as simple as rerouting the delivery truck; products are packaged and labeled differently for foodservice. To help keep food from going to waste and to get it to where it is needed most, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) loosened regulations with the publication of a temporary policy on March 26. For food manufacturers that have inventory on hand that is labeled for use in restaurants, the FDA does not intend to object to the sale of packaged food that lacks a Nutrition Facts label. Similarly, for restaurants that wish to sell packaged food to consumers directly, or to other businesses for sale to consumers, the FDA does not intend to object if the packaged food lacks a Nutrition Facts label.

Many creative solutions are being developed to get supplies where they need to be. Foodservice companies have begun selling grocery staple items alongside their prepared foods, while beverage distillers have turned their focus to producing hand sanitizer for frontline workers. But for manufacturers focusing on getting their goods to retail shelves as fast as possible, the pandemic is all about maintaining efficient production and keeping workers safe.

As the scope of the pandemic expanded in the United States, Nicole Linke, product development manager at The Suter Co., a prepared foods manufacturer in Sycamore, Ill., found herself working outside of her job description. “New product development is not on people’s minds right now,” explains Linke. “We have to keep production running and fill the grocery orders. My role has changed to reformulation of current recipes within FDA and USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture) parameters to keep production going with pressure on the supply chain. Each day brings a new challenge on what we may run out of or are just running low on.”

Larger food manufacturers with diversified supply chains may not encounter disruptions to the same extent, but small to midsize manufacturers started seeing disruptions in raw material availability as every link in the supply chain became stressed, and they lacked the manpower to produce at the speed needed. “Fortunately, we put a lot of focus on secondary sources of supply, and we have been utilizing those sources during this time,” says Linke.

Employees are filling roles that are needed to keep up with demand. “I come from a purchasing background,” explains Linke, “so I am supporting them in any way possible versus working on the next big thing … We have a small team—we have only one person on-site and others are working from home in our department. One of our team members has moved to a temporary role in quality to train as a back-up quality technician.”

Some job functions have been disrupted, but companies are adjusting in order to maintain a semblance of normalcy. Karen Graves, director of sensory and consumer insights (SCI) at Bell Flavors & Fragrances, has modified how she and her team are accomplishing tasks, but they continue to “guide projects and ensure Bell’s flavors and fragrances meet customer requirements,” she says. Part of her team’s job is conducting sensory tests, but maintaining social distancing and sample integrity is made much more complex during a pandemic.

“Bell’s SCI team is committed to continuing sensory panels—using employees—as long as they can be executed in a manner that meets CDC guidelines,” says Graves. To do this, the company implemented several tactical approaches, including suspending large panels and use of traditional sensory booths, swapping out the use of reusable plastic trays for disposable materials such as paper plates, and increasing panelist hygiene measures.

Workers are a vital cog in the food production wheel, which is why as the pandemic took hold in the United States in March, food manufacturers immediately took steps to ensure worker safety. “People who work at these plants are taking a lot of risks, and I think they are coming to work out of a sense of duty to keep the food supply at a comfortable level,” says Moskow. “But I’m pleased to see that the management teams have given those employees higher wages and more health benefits in exchange for that sacrifice.”

“Cargill’s key focus is on three things—safety of its employees, keeping food on the shelves, and avoiding food safety accidents,” says Sean Leighton, global vice president of food safety, quality, and regulatory affairs at Cargill. In March, Cargill announced it would pay U.S. and Canadian slaughterhouse workers a premium of $2 an hour until May 3, with a bonus of $500 to those who complete weekly shifts over a period of eight consecutive weeks.

General Mills said it would provide a daily bonus to “production essential plant employees” who are working on-site beginning March 18 and continuing for a minimum of four weeks. In addition, the company implemented a paid leave policy in which employees would receive two weeks of paid leave under conditions that include voluntary or mandated quarantine, school closure for a child, medical risk, and suspended work as a result of COVID-19.

PepsiCo followed suit on March 22, announcing a minimum wage increase of $100 per week for full-time employees and paid sick leave for its more than 90,000 frontline workers. Along with providing paid sick leave to ensure that frontline employees remain healthy, PepsiCo announced it would hire 6,000 new, full-time, full-benefit frontline employees across the United States in the coming months in preparation for when employees get sick with the virus or have to stay home to care for family members. Mondelēz International announced on March 23 that it expected to hire 1,000 frontline U.S. employees to ensure the uninterrupted functioning of its U.S. distribution and sales network in the coming months.

As the pandemic spreads and the likelihood of the food industry’s “essential workers” contracting the virus increases, many food companies are facing the fact that they may need to shut down or reduce operations. Early last month, meat plants became the center of attention as plant after plant reported an infection and/or death related to COVID-19. Smithfield Foods’ pork plant in South Dakota announced on April 9 that it would close temporarily after more than 80 employees tested positive for the virus. That same week, JBS, Cargill, and Tyson stopped operations as the virus seemed to pick up speed in processing plants where workers often stand close together cutting, deboning, and packing meat (Jordan 2020).

Manufacturers are working to ensure consumers have a steady supply of food while at the same time they must carefully consider their actions when it comes to the health of their workers. While many brands are seeing a resurgence in consumer interest and want to capitalize on an audience that may be trying their products for the first time, their success is also dependent on maintaining a brand image that puts people first. Companies that do both well could come out of the pandemic with a larger and more loyal consumer base.

Shoppers Stress Supply Chains

Bare shelves in supermarkets frustrated consumers during the early weeks of the pandemic, but supply chains were operating efficiently, experts say. The problems resulted when frenzied consumers started stockpiling products; thus, it was more a matter of demand than supply, they emphasize. “The consumer is part of the supply chain whether they know it or like it or not,” says Peter Bolstorff, executive vice president of the Association for Supply Chain Management.

Retailers and manufacturers maintain a certain level of “safety stock” that allows them to meet “normal” spikes in demand, but safety stocks were quickly depleted given the scale of the coronavirus crisis. In addition, for decades, manufacturers and retailers have operated using a just-in-time model, which focuses on reducing inventory and time to market.

“As [companies] looked to become more lean, they’ve invested in making their supply chains more agile, meaning that if they can replenish things faster, they are able to carry less inventory,” says Bolstorff. “If you don’t have a lot of demand spikes, that whole process is better, faster, cheaper.”

“Literally, we spent the last couple decades streamlining the supply chain,” agrees retail consultant Neil Stern, senior partner with McMillanDoolittle. “As a result of that, retailers have less stock in the back rooms,” he notes. “Traditional warehouses have become cross-docking facilities. Your emphasis is on the product sitting as little as possible in every step of the supply chain.”

Will the experiences of the pandemic trigger a shift in how retailers and manufacturers think about their supply chains? It very well might, the experts say. “I’m sure they’ll all be analyzing their current strategy, and you could see some reevaluating and possibly increasing safety stock,” says FMI’s Baker.

Bolstorff anticipates changes in several areas, starting with the use of new technologies and artificial intelligence insights to monitor potential supply chain risks and to allow companies to act on them quickly. “What we’re seeing is [that] companies are doubling down on digital capabilities in all kinds of aspects,” he says. “Where they had a digital transformation roadmap in place before COVID-19, they’re acting on it right now.”

After the COVID-19 experience, supply chains may become less global as companies move to reduce risk by identifying more local suppliers. Baker adds that thanks to recent tariff and trade negotiations, many companies in the United States had already begun looking for opportunities to source more products domestically. “In hindsight,” he says, “that was a beneficial activity.”

Going forward, Baker hopes to see more cross-sector collaboration that will allow players in the food system to respond even more effectively when a crisis arises. “It’s really looking at the reevaluation of the supply chain networks and the interface of technology to allow supply chains to enhance transparency [in order] to enhance sharing,” he says. In March, FMI announced that it had partnered with the International Foodservice Distributors Association to help channel unused foodservice resources (everything from food to transportation services) to wherever it was needed along the grocery supply chain.

Consumers: High Anxiety, Tighter Budgets

Just as the virus itself spread quickly across the country, so too did consumers’ financial concerns. “People are nervous about their personal health and their financial health right now,” says Driggs of IRI. “It’s a harder, faster adjustment for consumers than what occurred in the [2008–2009] recession.”

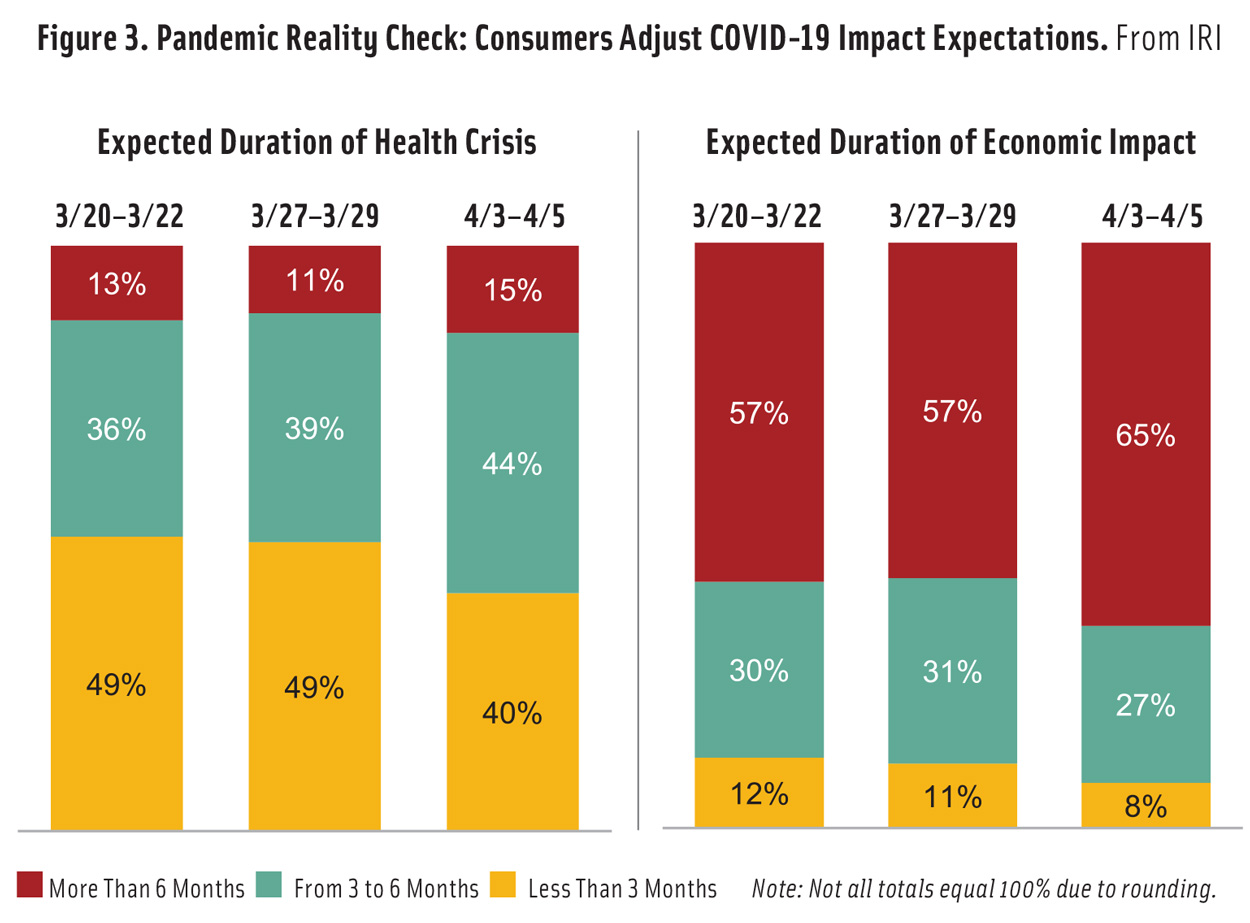

As of early April, 45% of respondents in a U.S. survey conducted by L.E.K. Consulting in partnership with Civis Analytics reported a decline in their income, and 97% said their geographic area had been affected by the coronavirus outbreak (Picciola et al. 2020). The great majority (between 85% and 90%) said they expected a recession in the coming year. IRI research shows that as the pandemic progressed, consumer expectations changed, with more consumers expecting it to have a longer-lasting health and economic impact (Figure 3).

Industry watchers agree that private label brands will get a major boost as consumers collectively tighten their belts. “I think we’re going to see some habits change because of some economic repercussions,” Stern observes. “We will likely mirror the habits of the recession … a boom in private label, a shift in channels towards more value-driven players. In the last recession, it was a huge stimulus for Aldi.”

“It’s a good opportunity for private label and what we would consider lower-tier, smaller brands that people might be giving a try because there are out-of-stocks on their favorite products, so they might be shifting,” says Driggs. “I think we’ll see things like ‘to go’ packaging go out the window. People are no longer interested in on-the-go products.”

“During the recession of 2008 and 2009, private brands did realize a spike in demand as consumers reevaluated their expenditures and the need to be smarter with spending,” adds FMI’s Baker. “Private brands were the winner. So I think if we find ourselves in an environment like that, an economic downturn, private brands will continue to grow. It’s still relatively underdeveloped in comparison to European countries. So there is still upward growth [potential] for private brands.”

Consumers already have high comfort levels with private brands, Baker points out, noting that 99% of households have private brands in their pantries. FMI does a private brands study annually, and the most recent one showed that nearly half (46%) of consumers choose their shopping destination based on the retailer’s private brands offerings, he reports.

REFERENCES

Albertsons. 2020. “Albertsons Companies Partners with Major Businesses to Offer Part-Time Jobs to their Furloughed Employees.” Press release, March 23. Albertsons Companies, Boise, Idaho.albertsonscompanies.com.

Brick Meets Click. 2020. “Online Grocery Delivery & Pickup Scorecard: March 2020—How do you compare?” https://www.brickmeetsclick.com/online-grocery-delivery---pickup-scorecard--march-2020--how-do-you-compare-.

Datassential. 2020. COVID-19 Report 8: The Operator Story. Datassential, Chicago. datassential.com.

FDA. 2020. Temporary Policy Regarding Nutrition Labeling of Certain Packaged Food During the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency. FDA-2020-D-1139. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Rockville, Md.

Jordan, M. and C. Dickerson. “Poultry Worker’s Death Highlights Spread of Coronavirus in Meat Plants.” The New York Times April. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/09/us/coronavirus-chicken-meat-processing-plants-immigrants.html.

Mandl, C. 2020. “Kraft Heinz Cuts Output at Three Plants, Adds Shifts for Mac & Cheese.” Reuters April. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-kraft-heinz/kraft-heinz-cuts-output-at-three-plants-adds-shifts-for-mac-cheese-idUSKBN21L30H.

NPD. 2020. “With 97% of U.S. Restaurants Impacted by Mandated Dine-In Closures, Restaurant Customer Transactions Declined by 42% in Week Ending March 29.” Press release, April 6. The NPD Group, Chicago. npd.com.

Picciola, M., M. Steingoltz, L. DeVestern, et al. 2020. “COVID-19 in the US: Consumer Insights for Business—Edition 2, Part 1.” L.E.K. Consulting, April 7. www.lek.com/insights/covid-19-us-consumer-insights-businesses-edition-2-part-1.

Polansek, T. 2020. “As Coronavirus Fuels Meat Demand, Processors Raise Pay for North American Farmers, Workers.” Reuters March. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-usa-meatpacking/as-coronavirus-fuels-meat-demand-processors-raise-pay-for-north-american-farmers-workers-idUSKBN21A3Z9.

Shake Shack. 2020. “Shake Shack Provides Business Update.” Press release, April 2. Shake Shack, New York. investor.shakeshack.com.

Technomic. 2020. “Technomic’s Take: COVID-19, The Foodservice View.” Press release, April 3. Technomic, Chicago. technomic.com.

U.S. Dept. of Labor. 2020. “COVID-19 Impact: Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims.” Press release, April 9. U.S. Dept. of Labor, Washington, D.C. dol.gov.

Yaffe-Bellany, D. 2020. “These Days, Even a Michelin Star Chef Has to Sell Takeout.” The New York Times March. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/30/business/coronavirus-restaurants-delivery.html.