Bringing the Store to the Door

Ocean Spray is in the business of selling bulky bottles of juice and bags of dried fruit, in high volumes, on long-stretching shelves in supermarkets and big-box retailers nationwide. Yet the retail transactions most important for the cooperative’s future may well be the relative trickle of sales that have begun at AtokaWellness.com, where Ocean Spray’s newest brand, Atoka, sells “herbal tonics” in 10-ounce bottles in varieties that include Calm Blend, Remedy Blend, and Restore Blend.

Ocean Spray pivoted to an e-commerce launch for its new line of Atoka herbal tonics this spring. Photo courtesy of Ocean Spray

The company was going to introduce Atoka the traditional way this year, in the wide and well-trod aisles of brick-and-mortar stores that it knows so well. But after the onset of the pandemic, Ocean Spray quickly switched gears in April, launching sales of the tonics just on Atoka’s website. Now it’s working with Amazon and other e-retailers to expand availability.

“We realized that consumers were changing quickly and were more open to look at doing things differently online,” says Rizal Hamdallah, chief global growth officer for Ocean Spray. “Even demographic groups that before weren’t comfortable with e-commerce—seniors, grandparents—are now kind of adapting and adjusting and can operate with it. It’s growing fast and becoming much more relevant.”

Indeed, when it comes to selling foods and beverages directly to consumers via e-commerce and new delivery options, the world already looks much like what many executives and entrepreneurs had envisioned for two to five years from now. Fear and the desire for convenience motivated by COVID-19 have prompted American consumers to pull online retailing volume ahead to levels many companies believed wouldn’t be achieved perhaps until the middle of the decade.

“We’ve seen an acceleration right now to numbers for online penetration that we were originally forecasting for 2025 or 2026,” says Mike Wystrach, co-owner and CEO of Freshly, America’s largest maker and distributor of fresh prepared meals. The pandemic “has drastically increased the number of people who want our product and are open to buying it, accelerating our growth plans. There’s been a massive transformation online.”

“A big part of the population is very comfortable shopping for their groceries online now.” —Greg Wank, Anchin

“A big part of the population is very comfortable shopping for their groceries online now,” agrees Greg Wank, lead of the food and beverage group for consulting firm Anchin. “Consumers get it and understand it and can see the quality is pretty much the same. People used to say they didn’t want to shop online or get delivery because they wanted to pick out their own produce; you don’t hear that anymore.”

At the same time, the incredible telescoping of online demand has “forced companies to do SKU rationalization and delivery straight to customers on the fly,” says Patrick Van Hull, industry thought leader at Kinaxis, a supply-chain software company. “That has accelerated their transformation plans. I’ve seen five years’ worth of innovation in five weeks.”

Indeed, paradigms for success, and even survival, have shifted abruptly and significantly for companies both big and small, with the likelihood that the acceleration of e-commerce they’re experiencing now may slow—but that direct-to-consumer (DTC) as a main driver of the food business is here to stay. Along the way, companies are learning about and improving aspects of their operations, ranging from packaging to social media marketing, in order to adjust to and take advantage of the new realities.

The food industry has long been a laggard when it comes to e-commerce, but legacy food and beverage brands are catching up in a hurry. Meanwhile, consumer packaged goods (CPG) startups that have been hatched in a DTC-only mode are trying to take advantage of how they’ve relied on e-commerce right out of the gate. Food retailers and foodservice operators are similarly adjusting. (See sidebars.)

The food industry has long been a laggard when it comes to e-commerce, but legacy food and beverage brands are catching up in a hurry.

Consider that last spring PepsiCo developed and launched two new DTC websites, Snacks.com and PantryShop.com, less than a month after consumers’ pandemic shopping and stocking patterns became evident. Kraft Heinz created its first ever DTC business line, bundling shelf-stable items including beans, spaghetti, condiments, and soup for home delivery in the United Kingdom. And AB InBev is shifting its drinks to produce more of them in large packs, which are more efficient to ship and sell online where consumers favor bulk volumes, not ready-to-drink singles. Startup SnackMagic, meanwhile, recently popped up on the web offering 500 SKUs of snacks from more than 200 brands, many of them obscure upstarts that haven’t gotten broad exposure in stores.

Ocean Spray’s Paradigm Shift

Consumers in Ocean Spray’s test markets in 2019 responded favorably to Atoka beverages with their better-for-you blends of herbs and other botanicals including rosehips, elderberries, ginger, hops, lemongrass, and linden flower. The company planned to roll out Atoka in natural grocery retailers and build the brand from there mainly through bricks-and-mortar exposure.

Then in March, COVID-19 hit in a big way. So shifting the Atoka launch to e-commerce made sense because the brand was facing a difficult period for getting panicked consumers to relax and linger in a grocery store and try something new. But Ocean Spray faced an unfortunate reality: The company had no significant experience going directly to the consumer.

“We had talked about it,” recalls Hamdallah, who joined Ocean Spray in 2019 as chief global innovation officer after spending three years heading innovation at Tyson Foods. “But could we do it? None of our existing brands had been strong in building this capability.”

Atoka did have some advantages for DTC success through Ocean Spray, including plenty of data about the company’s customer base. Hamdallah and his team began promoting Atoka via social media and targeted marketing. During the pandemic, he said, “a lot of new brands appeared, such as the ones selling masks and other stuff for working from home. You hadn’t seen those brands before either, but their marketing was targeted to you. So we had the same opportunity to grow as an existing brand.”

Also, in communicating with consumers in a DTC world and educating them about the benefits of its products, Ocean Spray could rely on its legacy as a health-oriented brand in part because of how it has leveraged the connection between cranberries and urinary tract health over the years as well as the fruit’s rich antioxidant content. In fact, cranberries’ proven immunity-boosting benefits in the midst of broad germophobia may help lead the way for Ocean Spray’s marketing as the company’s main brands begin to explore DTC, too.

“The challenge is that consumers are overwhelmed with information,” Hamdallah says. “Knowing consumers are exposed to a lot of things digitally, it’s become our opportunity to create the right matchmaking process. We need to become the brand digitally helping consumers find the right solutions, not just the one that wants to be present in the buying process only.”

Ocean Spray isn’t alone in facing obstacles in the industry’s new emphasis on DTC. E-commerce may be disqualified for some entire industry categories. Crystal Farms, for instance, has just introduced a popular new product: cheese slices proportioned to replace bread as sandwich wraps. But the largest cheese brand in the Upper Midwest is only going so far in e-commerce, cooperating with the curbside pickup and home-delivery programs of bricks-and-mortar retailers, for example. “It’d be too expensive to have our own system to maintain product quality and delivery at the right temperatures,” says Katie Egan, director of marketing and product development.

The fast-rising popularity of DTC has broad implications for food delivery of all kinds. If the new means of consumption is opening their front doors to find foodstuffs in a box, Americans don’t necessarily need to dip into a parcel to find only brands, product forms, and packages that are familiar to them from trips to the supermarket. So the pandemic has quickly expanded market opportunities for meal kit and meal delivery brands.

Boom Times for Meal Kits

After a strong boom during their first few years, meal kit startups faced trouble recently as many millennial consumers soured on the proposition. Among the problems: They found that regular meal kit subscriptions simply required too much regimentation and predictability in household schedules that couldn’t be tamed. In any event, pressure was growing on pioneers such as HelloFresh and Blue Apron to maintain growth and turn profits, while another of the early prominent meal kit entrants, Chef’d, ceased operations for a while in 2018 after it couldn’t secure fresh capital to keep its complex operations going.

The pandemic produced a bump in meal kit sales for companies such as Blue Apron. Photo courtesy of Blue Apron

COVID-19 changed the picture dramatically. Deemed “essential” businesses by the government, meal kit operators saw revenues and customer bases expand significantly during the first and second quarters, in some cases doubling. Blue Apron added 200,000 customers during the first quarter, a huge turnaround for a company that was on life support late in 2019. HelloFresh took such encouragement from the bump in its business during COVID-19 that the company now plans to build its largest-ever distribution center at the Dallas Fort Worth International Airport next year, in addition to a new distribution facility in Georgia.

The meal kit boom also saw some pressure for consolidation so that players could take advantage of expectations that the whole industry must scale up. Grubhub, for example, was headed toward a potential acquisition by Uber until some U.S. senators grumbled about antitrust implications; Grubhub instead merged with European company Just Eat Takeaway.

The sharp uptick in fortunes for meal kit delivery attracted new competitors as well, with chain restaurants coming up with assemble-your-own alternatives as their on-premises sales dwindled to practically nothing. Coming on top of restaurant expansion of delivery of already-prepared goods, these new branded meal kit entries included Shake Shack’s burger kits, Panera Bread’s salad and sandwich kits, and Chick-fil-A’s chicken dinner kits.

Freshly’s proposition is a bit different. It delivers high-protein, low-carb breakfasts, lunches, and dinners fully prepared, shipping them in refrigerated packaging via freight trucks and FedEx, requiring only heating before eating. Or, in the words of a consumer portrayed in a new television ad by Freshly, “We don’t have to cook anymore!” In the commercial, her refrigerator opens to show Freshly’s world of culinary possibilities: a stack of meals in cardboard boxes including Chicken & Rice Pilaf, Sausage & Peppers w/Cauliflower, Steak Peppercorn, Southwest Chicken Bowl, and Penne Bolognese.

“We’re one of the most efficient channels because of our use of data forecasting and predictability.” —Mike Wystrach, Freshly

Now Freshly is delivering meals at the rate of about one million a week nationwide, for an average price of about $10. In other words, the five-year-old company already is about a half-billion-dollar operation. Freshly boosted its manufacturing capacity by 20% this year at its handful of kitchens across the country, and Wystrach plans another 60% addition to capacity for 2021.

Wystrach gives much of the credit to post-COVID shopper psychology. “Consumers who weren’t willing to go online and make food purchases before now are a lot more inclined,” he says. “For most Americans, cooking is transferring to entertainment occasions. Otherwise, convenience is really important to them.”

For DTC brands like Freshly that have a huge service aspect in addition to providing products, digital connectivity is crucial. “We make it insanely easy for people to manage their food purchases” with smartphones and 24-7 customer support, he says. “You can place, pause, and skip orders, and we make it easy. Our mission is to make it unbelievably easy to eat healthy. “

Freshly is shipping about a million heat-and-eat meals a week and will expand production capacity next year. Photo courtesy of Freshly

Freshly harnesses data to match production to customer demand, cutting food waste. “We’re using fresh products with short shelf lives—and getting less than 50 basis points of waste,” Wystrach notes. “We’re one of the most efficient channels because of our use of data forecasting and predictability, making sure we’re producing exactly for demand and that we’re not over-producing food.”

The company also is pivoting to take advantage of the nearly complete shutdown of foodservice on corporate campuses across the country. It launched Freshly for Business during the pandemic and now has recruited more than 70 employers that want to provide fresh meals to workers—and even their families—at home, on a fully or partially subsidized basis.

“Meals in the office led to a drastic increase in productivity,” Wystrach says. “And now people are busy as ever with back-to-back Zoom calls. We’re affordable, taste great, and are prescreened to be healthy as companies look to help employees fighting increasing health-care costs.”

As employers continue to climb out of the pandemic and many resume on-premise activities, Freshly plans to add more menu items to its business program and allow clients to designate meal delivery to a worker’s home or a company site. “Employers are going to assign a certain number of meals to the benefit, and how they get consumed is really up to the employee,” Wystrach says.

Closely watching Freshly is Nestlé, which is a major investor. Right now, Freshly isn’t explicitly including Nestlé products in its meals; there’s no co-branding. But Wystrach says his company is working with Nestlé developers “on product alignment, as they’re doing a lot of stuff around alternative proteins.” And he says that Nestlé, like other CPGs, is monitoring fresh-meal delivery services in general to detect changes in consumer behavior toward DTC food.

Supply Chain Imperatives

One thing all CPGs are working out in e-commerce is balancing their growing desire to cull marginal SKUs, for greater efficiency, while at the same time taking advantage of the essentially infinite merchandising possibilities online and of the potential to satisfy even consumers at the very end of a long, long tail of demand for very specific products.

“I’ve seen five years’ worth of innovation in five weeks.” —Patrick Van Hull, Kinaxis

“Companies have to be very focused on those products that are most desirable for customers and most profitable for the business, on creating choice for customers without overextending their supply chain,” Van Hull says. “‘We’re going to expand our portfolio and give customers unlimited choices’ sounds great in theory—until you execute against it. If the supply chain can’t deliver, that will frustrate the customer.

“But if you can create the perception of choice, that’s when you can start to build loyalty and delivery consistently and provide the customer with what they want, when they want it, and where.”

Hint inc. has used DTC to try to create such a “perception of choice” about flavors of its fruit-infused sparkling waters. The $150 million brand doesn’t try to beat Amazon on prices for its products but ensures that its own e-commerce capabilities mean customers can get any of the couple dozen varieties of hint water, while perhaps paying a bit more for the privilege.

“We want to make sure that when you want your Strawberry Kiwi hint, you’ll be able to get it,” says Kara Goldin, hint inc.’s founder and CEO. This capability also provides insurance should a bricks-and-mortar retailer opt to reduce shelf space for hint water.

The brand’s approach also illustrates how the most sophisticated CPG marketers are approaching e-commerce: from the viewpoint of today’s ominichannel consumer who may “be buying cases of hint water online but then walks into a Target store, sees ‘10 for $10’ on an aisle, and decides to load up on it there,” Goldin says. “It’s about being truly about the customer and not about choosing where they’re ultimately going to buy hint water.”

Indeed, many of today’s startups continue to harbor the desire to get on actual store shelves and are leveraging e-commerce partly to demonstrate a level of consumer demand, and manufacturing scalability, that will impress buyers for Walmart or Target or Safeway or Kroger—as well as investors.

“The thesis is that if you can build a foundation on DTC, a higher-margin business that requires less cash, then you can take it to stores and get more leverage with them,” says Wank, the consultant. “Maybe your brand won’t have to pay the full price for slotting fees if you’re coming to them with some e-commerce sales momentum and a following of your own.”

Treo is one brand that professes little interest in DTC. For the new line of birch water flavored with fruit essences, beverage shipping costs via e-commerce are prohibitive, says Bob Golden, founder of the startup. Plus, he says, “I wanted to get the product out there in distribution where people see it wherever they go in supermarkets, in down-the street stores, [and in]pizza and bagel stores.” Golden already has built a multimillion-dollar brand without e-commerce.

Yet Wank and other experts believe most CPG brands big and small are going to take their 2020 experience with DTC, learn from it, build on it, and never look back.

“Just thinking about the lower cost of customer acquisition and the higher gross margins online, and the loyalty you can build, it’s so much more cost-effective than what it takes to do all of those things at retail,” Wank says. “You’re sitting there among competitors and paying for promotion and shelf space. Investors and stakeholders are going to demand more DTC. It needs to be an important part of every food company’s business post-COVID.” Given all the new initiatives implemented since the start of the pandemic, odds are good that a brand-new era of CPG DTC has just begun.

Seizing New ‘E-Opportunities’

The rise of direct-to-consumer sales of foods and beverages presents an obvious challenge to traditional physical retailers. But some opportunity lurks as well.

“Retailers are really going to have to justify why they’re worth the price of admission,” says Greg Wank, a consultant with Anchin. “I’d rather have a robust online business than a robust retail business right now.”

Photo courtesy of Meijer

How about both? Meijer is a major regional superstore retailer that leaned into home delivery and curbside pickup five years ago and committed to delivery chain-wide through Shipt, whose black-shirted item pickers now can be seen pushing their carts and poring over their orders at Meijer’s 250 bricks-and-mortar stores around the Midwest.

At the end of last year, Meijer also launched its own pickup-and-delivery platform to continue reaching new households and integrate them into the chain’s preexisting promotional and customer loyalty programs.

“We’ve seen explosive growth across all metrics” from digital delivery platforms, says Justin Sessink, Meijer’s director of digital shopping.

Meijer also is working with CPG brands for specific e-commerce promotions, in part because “basket mix and customer buying habits differ between in-store and digital channels,” Sessink explains. Food and beverage brands also “bring insights that help us optimize our ‘digital shelf’ by having online purchase data from retailer sites nationally. That helps us determine better ways to merchandise categories on digital devices, including menu structures and search strategies.”

Indeed, Meijer is an example of the potential for traditional retailers even amid the boom in DTC. “Consumers still look at the retailer brand as the delivery mechanism for goods,” says Bill Aull, a managing partner of the retail and packaged goods practice for McKinsey consultants. “The openness to Procter & Gamble or Unilever saying they’re going to start shipping things to them directly doesn’t fit into the mindset at the moment. Consumers are wondering, ‘Where’s the aggregator of products?’”

Another advantage for retailers is that, for all of consumers’ new willingness to try e-commerce, there are some things about bricks-and-mortar stores that retain great appeal for food shoppers. “There’s very strong convenience and an ability to get all the things you need in one place,” Aull says. “With CPGs trying to [sell] everything directly, they’re disaggregating that, and today there still isn’t an online platform that aggregates everything well except Amazon.”

A growing number of retailers also are creating “micro-fulfillment” centers that employ more automation than in the backrooms of stores. Retail chains are attaching such operations to existing outlets or building them in separate locations. They may be half the size of a store and carry half the range of SKUs.

Meijer, for instance, opened its first microfulfillment center earlier this year and since has rolled out a hub-and-spoke network model to optimize efficiencies, Sessink says. “Every retailer is trying a new angle on this,” Aull notes.

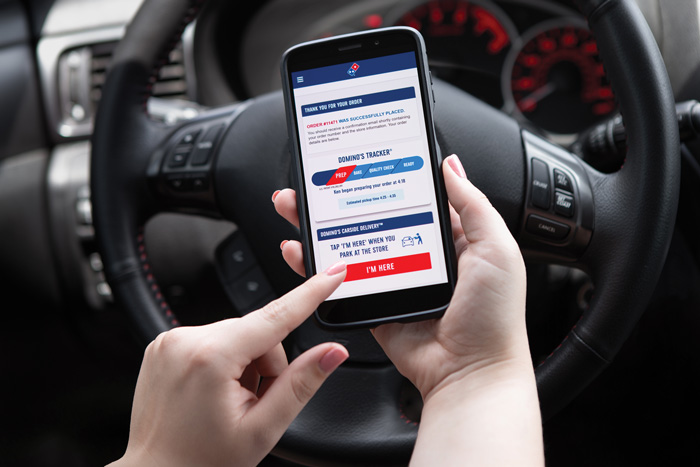

Domino’s Doubles Down on Delivery Options

Before COVID-19, restaurants were more advanced about online ordering and home delivery than CPG companies. And with the onset of the pandemic, which shut down on-premises service at most eateries, delivery capabilities became more important than ever.

Photo courtesy of Domino’s

Take Domino’s, for example. The world’s No. 1 pizza brand has always been mostly delivered, and over the last decade, it took the industry lead in online ordering technology that helped the chain zoom past Pizza Hut. Well over half of Domino’s orders came via e-commerce even before the virus hit.

Since COVID-19, Domino’s has leveraged its impressive digital tech capabilities to take advantage of Americans’ increased appetite for home-delivered pizza and to expand its market dominance. This has included a new contactless delivery method in which workers place pizzas atop a box outside customers’ homes, notify them, and then move six feet away.

And Domino’s later added a new feature for store-pickup orders that allows drive-in customers to describe their vehicle and indicate where they want their food placed by the restaurant worker.

“We needed to make a number of operational changes like these very quickly and roll them out to a system of 6,000 stores” in the United States, says Kelly Garcia, Domino’s chief technology officer.

“We were able to pivot very early in the pandemic and very quickly,” Garcia continues. “And we think it’s likely customers will want options for contactless commerce going forward.”

As for more far-out delivery options with which Domino’s has been experimenting, including autonomous pizza-delivery vehicles and even delivery drones? Progress toward such methods understandably has been stalled by the pandemic.

“But we still believe that the ability to do autonomous delivery is going to be important for us to understand in the future,” Garcia says, “and we intend to continue to learn and test these technologies.”

Hero Image: Copyright @ Walter Cimbal / StockFood

Authors

-

Dale Buss Journalist

Dale Buss, contributing editor, is an award-winning journalist and book author whose career has included reporting for The Wall Street Journal, where he was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize (daledbuss@aol.com).

Categories

-

Food Business Trends

-

Foodservice

-

Consumer and Marketplace Trends

-

Food Retailing

-

Food Technology Magazine