Balancing the Global Diet

Profile | RESEARCH

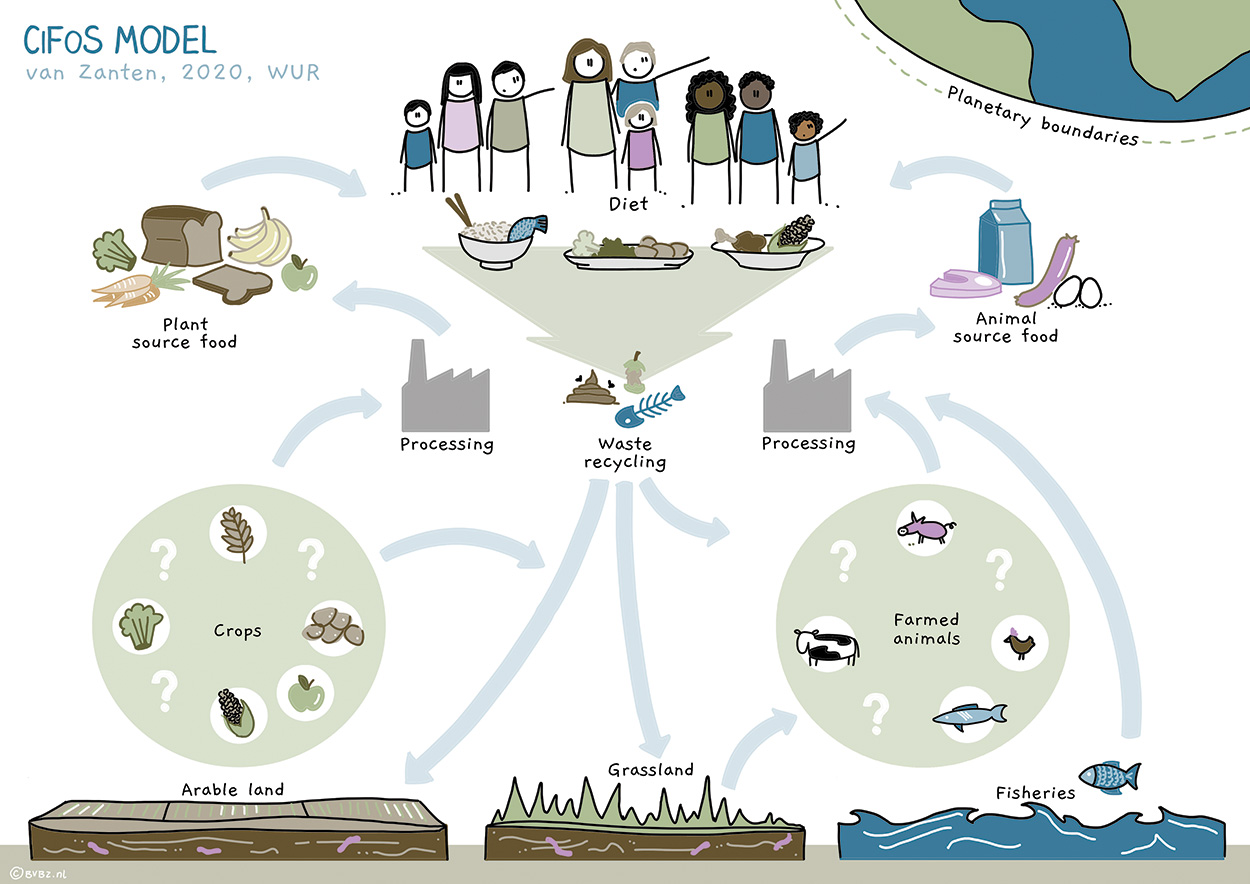

How do we move to a food system that’s healthier for the planet, while still providing sufficient high-quality nutrition for people? Wageningen University’s Hannah van Zanten believes the answer lies in developing new food system models. So she created one.

There are already food system models available, but they are too simple and don’t include circularity, says van Zanten, an associate professor of farming systems ecology in the Department of Plant Sciences at Wageningen and a visiting professor at Cornell University.

Understanding all the relationships within food systems is important, she says, because otherwise we can only create single-issue answers. “You don’t see the potential consequences that can happen somewhere else, and then we never come to solutions that will actually overall improve the sustainability of the food system,” she says.

Van Zanten’s Circular Food System (CiFoS) model for sustainable circular food systems seeks to find the best balance between plant- and animal-based diets, the environment, and nutritional needs. It earned her a GroundBreaker Prize of $150,000 awarded by FoodShot Global, an investment platform designed to serve as a catalyst for food chain innovation.

Van Zanten says she is driven by the challenge of finding a model that balances simplicity with the intricacies of feeding the world. “How can we make as simple a model as possible that is still able to embrace the complexity and therefore avoid potential trade-offs if we are looking for solutions?” she asks.

Better Diets, Better Planet

The CiFoS model can be used one of two ways: to figure out the outcome of using land a specific way, or to determine how to use land to fulfill nutritional requirements. The model includes plants, animals, and environmental impact of land use, all of which is balanced against a healthy diet of minimal red meat and sugar, and enough fiber and plants. The results detail which crops to grow and where, which animals to keep, how many, how productive those animals should be, and how crops ought to be fertilized.

“It will make all those decisions,” says van Zanten. “All those things are the outcome of the model in such a way that we minimize the environmental impact and still produce healthy foods.”

In theory, the CiFOS model offers the potential to avoid waste entirely. It’s likely not realistic to achieve that, but van Zanten says adoption of the model would mean minimizing food waste and finding good uses for what is produced. For example, with the model, livestock could be fed food waste and byproducts instead of food that people eat, which is common now. Such an approach could result in a 31% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and would require 42% less farmland, according to recent research that van Zanten co-authored. “If we don’t stop wasting, we should at least use the waste in the most efficient way that we can use it,” she says.

It’s easy to focus on a single solution for what ails our food system, says Sara Eckhouse, executive director of FoodShot Global. But embracing its complexity and circularity is essential, she says, to optimize and improve nutrition, nutrient resource management, and environmental stewardship.

“We can only do that if we actually have an understanding of that system and how all of these different pieces work together,” which is what van Zanten’s model provides, she says. “We see that kind of broad systems approach as what we need more of. Having that information is a key part of being able to figure out what we need to do to move forward.”

Scaling Up

Van Zanten says the entire CiFoS food system model for Europe is almost finished and can be scaled to a global level. Different countries have different zones based on climate and soil conditions, which means different potential crops. These are “not necessarily the crops that we grow there now, but the crops that we could grow there based on the soil and climate conditions,” she says.

The GroundBreaker Prize money and the connections that resulted from it—which helped van Zanten win another big grant—have allowed her to hire and expand the model globally. Her team is planning case studies in Ethiopia, Kenya, Uruguay, Colombia, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and New York state to explore approaches to localizing the CiFoS model. They want to see if the model is sensitive enough to find practical solutions in different countries. One example: eating insects.

However, many countries, particularly those where incomes are lower, don’t have data about their existing food systems. Van Zanten says she and her colleagues are very dependent on local collaboration.

“I thought, ‘I can make this global model in one go,’” she says. But that is not the case. She realized that “I just need to take this much more country by country and really build on the ground and discuss [it] with people.”

Van Zanten’s team also plans to simplify the model so it runs faster and can be “gamified.” The idea is for it to be used on a tablet, enabling the user to create his or her own food system by selecting crops, animals, etc., and to see the environmental impact of those choices.

“I hope by creating such a game, you have different stakeholders building the food system together,” explains van Zanten. “They will need to start talking and negotiating about what they want to keep to actually stay within planetary boundaries while still producing healthy food.”

Building a better food system that is policy oriented and based on science will inform how those decisions should be made, she says. Only then will we truly understand the health and environmental domino effects of food system choices and come to a consensus on action.

“We need to talk and agree about where we want to go with the food system,” says van Zanten. “Then we can better provide the tools to all the different stakeholders.”

Vital Statistics:

Hannah van Zanten

Credentials: MS in Animal Science, Wageningen University; PhD, Wageningen University

Recognition: NWO (Dutch Research Council) Talent Scheme grant