Importing Good Packaging

PACKAGING

As globalization has proceeded and we have become more attuned and dependent on each other, not all that dazzles from faraway places is truly gold. In fact, some of the more majestic offerings are fool’s gold.

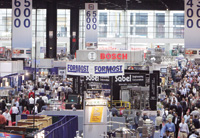

We in food packaging have become accustomed to being awed by the innovations showcased at the European and Asian packaging exhibitions such as Interpack and Japan Pack that still seem to (barely) outshine our own wondrous Pack Expos. Machinery from the great German, Swiss, and Swedish engineering firms remains the gold standard of precision, accuracy, and reliability. Most of us marvel at the intricate and elegant packaging structures that appear to be the norm in Japan. And professional acquisition executives appreciate the materials competitively available from the Latin American, Asian, and European continents and even from our own neighbors on the North American continent.

We in food packaging have become accustomed to being awed by the innovations showcased at the European and Asian packaging exhibitions such as Interpack and Japan Pack that still seem to (barely) outshine our own wondrous Pack Expos. Machinery from the great German, Swiss, and Swedish engineering firms remains the gold standard of precision, accuracy, and reliability. Most of us marvel at the intricate and elegant packaging structures that appear to be the norm in Japan. And professional acquisition executives appreciate the materials competitively available from the Latin American, Asian, and European continents and even from our own neighbors on the North American continent.

Since a few tiny irresponsible companies suffering from a paucity of integrity can sully the reputations of sound offshore competitive operators, here are some points to reflect on regarding the merits of "incredible" food package offerings from other countries.

Good and Bad

Although Americans did not necessarily invent food packaging, we have been among the drivers for the protection, safety, and quality imparted to and retained by our food supply for the more than two centuries of existence of food technology and its logical offspring, packaged foods. And we surely developed food packaging into the most sophisticated system in earthly chronology. We built a food supply that is the safest, most diverse, highest quality, and most economical in world history. And we have gratefully taken from our overseas brethren what we regarded as the best and applied it to enhance our food product, packaging and distribution systems.

Simultaneously, we have shared our mutual experiences with folks abroad to improve their food packaging. And we have generally welcomed the clones and improvements in food packaging that they have often exported to us. Indeed, some of the good imitations have been "low price," but even these inexpensive but still functional versions have fulfilled objectives for small food companies, for startups, for product introductions, and even to generate lower-cost derivatives, all the price of a vigorous free market economy.

American food packagers have vast networks of sources around the world. We import mammoth quantities of oriented polypropylene from the Asian continent east and west, from Indonesia, Canada, Mexico, and elsewhere. We import oxygen scavengers from Japan, Taiwan, and Korea. We import can ends from Italy, glass bottles from Poland, flexible barrier structures from Brazil, and an array of other "stuff" that fits into our $60-billion annual food packaging budget. Some of our most-trusted food packaging vendors are foreign born and bred: Tetra Pak, Amcor, Alcan, Rovema, Krones, Bosch, Fuji, Fres-Co, EVALCA, and many others.

However, a very few other companies, through ignorance, greed, or malice, have maligned the high repute of those who daily cross our borders with and maintain high standards of excellence in their products and dealings.

• Retort Pouches. The retort pouch was invented and developed in the United States but eventually commercialized in Asia. Most of the growing population of tuna in pouches continues to be sourced from Thailand, with no known adverse episodes. If Thailand can be a valid source of packaged product, then, of course, it follows that East Asia might be an honest source of retort pouch machinery, materials, and structures. Indeed, many of those bold American food companies which are not government contractors and which have dared to venture into the highly involved world of retort pouches and trays have successfully imported from Asian suppliers. The responsible intermediaries have triangulated effectively and, presumably, profitably.

But products with visible appeal and potential profitability spawn competition. Some unschooled in the intricacies and hazards of retort pouch packaging have attempted to penetrate the market. If aseptic packaging of low-acid foods is the single riskiest food packaging operation, then retort pouch packaging of low-acid foods is a close second in potential danger to the consuming public. Retort pouch packaging is not a technology that can be grasped through a sales pitch. Nevertheless, there are companies here and abroad that avoid any semblance of understanding and attempt to sell deficient offshore goods for retort packaging with rosy assurances of "no problem." They offer retort pouch structures that are said to be used by one or another Asian food company by the millions with "no problem."

Retort pouches represent a clear example of high risk whose trivialization must be obliterated if this technology is ever to achieve the promise expected of it.

• Residual Odors in Package Materials. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) long ago restricted emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from all factories, including package material converting plants, but U.S. regulations do not limit many offshore converting operations. Thus, solvents long since abandoned for all practical purposes from our converted package materials and structures may be present in some of our imports.

American converters have invested in, installed, and are operating the expensive equipment to incinerate or recover solvents from their printing, coating, and laminating processes. They and their responsible overseas competitors and associates long ago eliminated the use of VOCs, for commonsense reasons: the residuals are offensive odors that inevitably turn away numbers of consumers who express their disapproval by no longer purchasing the offending product. The numbers of failed food products is staggering and measurably costly, and one of the major reasons is flavor problems, including offensive odors.

Most large and many smaller American food companies write their packaging specifications explicitly citing the absence of any residual solvents—effectively zero-tolerance rules. Those not incorporating this prohibition are comforted by the wisdom that no vendor would intentionally or inadvertently include residual adverse odor-producing compounds in any quantity in any product intended for or which could conceivably enter a food product. The risk is too high for the food company and the vendor. And every responsible converter that has inadvertently permitted this malfeasance immediately implements a recall.

In contrast, VOC-laced package material from an Asian converter unhampered by EPA or Food and Drug Administration regulations might be exported to the U.S. with assurances that it is fit for use as a food package material. However, the material might reek of evaporating residual solvent resulting from archaic printing processes not uncommon in some few Asian operations. These solvent levels could threaten not only the contained food but also the food packaging operational environment. The reassurances of "no problem" might be repeated by an intermediary wanting to avoid the financial losses from this one unfit shipment.

How to Avoid Problems

Relationship marketing, a fundamental concept that underlies our economy, mandates that long-term sales depend on the continuous small steps of ensuring that the customers—in our example, food packagers—are not just satisfied but delighted. It does not abide one-time orders supported by opportunistic perks. And relationship marketing, memorialized by years-long contracts among package material suppliers and food packagers, is invariably mutually profitable.

The warning to beware of strangers bearing gifts has been updated in contemporary idiom to "If it appears fantastic, it almost certainly is." Present and potential food packagers everywhere should examine carefully the offerings of all unknown vendors and intermediaries. Deliberate and continuous uncompromising monitoring of the packaging products and their sourcing should be a mandate in such situations.

Look at the packaging product, smell it, place it on your packaging machine, and evaluate closure and structural integrity interactions with the food contents. Conduct a few qualitative sensory tests. Assurances of "no problem" from the salesperson are insufficient. Demanding functional test results from responsible professional sources should be the rule. Most materials will pass; those few which do not must be barred.

Food packaging cannot afford episodes of even a few ultimately destructive vendors tossing off fantastic claims that in the end harm the food product. Food packaging cannot afford irresponsible suppliers who are ignorant of the rules by which we have delivered an ever-safer packaged food supply or who choose to ignore them.

Knowledgeable, intelligent, and well-educated food packaging professionals are our bastions of protection against these forces, and our leaders into global successes in food and packaging.

Guidelines for selecting a qualified vendor

Research the vendor, particularly if the product or service has not been purchased before. Among the tools available for this are:

• Library reference publications.

• Internet sites.

• Trade publications, directories, vendor catalogs, and professional journals.

• Salespersons.

• Colleagues in other companies who might have purchased a similar product or service.

Evaluate the vendor’s capabilities:

• Financial stability.

• Bank references.

• Annual report, if available.

• Length of time vendor has been in business.

• References from vendor’s primary customers.

• Production equipment and facilities.

Adapted from Harvard University’s procurement manual (http://vpf-web.harvard.edu/ofs/procurement/pro_gui.shtm), accessed January 2007.

by Aaron L. Brody, Ph.D.,

Contributing Editor,

President and CEO, Packaging/Brody, Inc., Duluth, Ga.

[email protected]