Phenolic Antioxidants and Prevention of Chronic Inflammation

Chronic inflammation is associated with conditions and diseases resulting from overweight and obesity. Antioxidants in the diet may reduce the consequences of chronic inflammation.

The United States is currently facing a major obesity epidemic, with 64% of the population being either overweight or obese. The concern is not unique to the U.S. but is spreading to the rest of the world at an alarming rate. The rapid increase in overweight children and adolescents over the past five years has triggered alarms with physicians, educators, and, more recently, politicians.

There is an unfortunate reality that currently most weight-loss programs simply do not work. Most overweight and obese individuals are not likely to permanently lose sufficient weight to fall into the ideal range. Their lack of success is likely due to many of the same reasons why they became overweight in the first place. Another major problem is that many individuals who do lose weight cannot maintain the weight loss over extended periods of time.

Obesity has many causes that range far beyond the scope of this article. Obesity and overweight result from complex combinations of genetics, environment, social pressure, and personal choice. We eat for many reasons, including basic needs, social experiences, reward, and others, and sometimes simply because the food is there. Food now seems to be available wherever we go. Many people are constantly snacking and drinking. One might consider that food for some individuals has become a replacement for smoking. Because food is available wherever we go, we consume it. At the same time, our society has evolved away from physical labor to more sedentary activities. Rather than walk, we drive. Mechanization has greatly reduced the need for physical labor. And television and computers furnish all of us with hours of enjoyment, but these are sedentary activities.

All of these factors lead to the simple and often oversimplifying concept that we take in too many calories and burn too few. We should also be reminded that weight gain generally does not occur rapidly. We see a few extra pounds a year, and concerns that “I can’t do as much physically as I used to” and “I don’t look as good as I would like” are not enough of a motivator to overcome the multiplicity of other factors that ultimately lead to weight gain.

What’s Bad About Overweight

The greater overriding concerns are the negative health implications of being overweight. Health professionals now predict that for the first time the current generation of children will not be as healthy as their parents, primarily because of the high incidence of being overweight and obese.

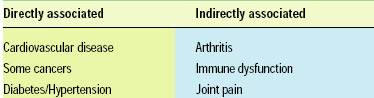

Table 1 lists some of the negative health effects associated with overweight and obesity. Being overweight or obese can lead to a negative cascade of conditions that eventually lead to a downhill health spiral. As individuals gain weight, they tend to become less active but continue to consume excess calories. The insidious nature of the problem is that as little as 100 kcal/day excess can lead to 10 lb of weight gain in a decade.

The chronic conditions listed in Table 1 will occur in different orders and at different frequencies in individuals, based on their genetics and environmental factors, including diet. Typically, there is a cascade associated with becoming overweight or obese, which leads to the metabolic syndrome followed by diabetes, which can ultimately be a precursor to cardiovascular disease. In overweight individuals, there is also greater risk of some types of cancer, arthritis, and immune dysfunction. Oxidative stress and chronic inflammation appear to be a common thread associated with conditions and diseases which are consequences of being overweight or obese.

Obesity in the absence of clinically diagnosed diabetes or cardiovascular disease is characterized by increased low-grade inflammation. Thus, diet and obesity may exacerbate low-grade inflammation associated with chronic diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Inflammation is a normal response of the body to repair injury and repel infection. However, chronic inflammation is less desirable and ultimately leads to negative health outcomes.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

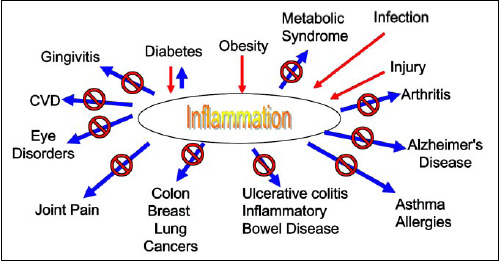

Fig. 1 illustrates three pathways by which diet and obesity can lead to or exacerbate chronic inflammatory conditions. Many of these conditions are age related, and there is some speculation that control of oxidation through antioxidant-rich diets may delay the aging process.

Recently, it has been documented that adipose tissue, particularly central or abdominal adipose tissue, produces inflammatory cytokines, which act to increase chronic inflammation, particularly in cardiovascular tissue. Chronic inflammation of cardiovascular tissue leads to atherosclerotic lesions. Diet and eating habits can significantly increase the risk of chronic inflammation. There is an increased incidence of free-radical production observed when diets are high in saturated and trans fats.

There is rapidly growing evidence that chronic inflammation is heavily implicated in many chronic conditions associated with aging. Heart disease, some cancers, diabetes, arthritis, and Alzheimer’s all include inflammatory components. The cause and effects of the relationships are still being resolved. Prevention or delay of these outcomes through dietary intervention is a laudable goal.

Dietary Causes of Inflammation

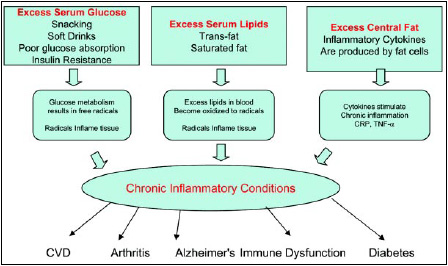

It is somewhat counterintuitive to think about saturated fats and trans fats as sources of free radicals. Food scientists are all aware of the propensity for polyunsaturated fatty acids to become oxidized, resulting in off-flavors in foods. In the body, unsaturated fatty acids are enzymatically oxidized to produce prostaglandins, lipoxins, and leukotrienes (Fig. 2) (Pischon et al., 2003). Saturated fats and trans fats are oxidized by a different pathway, primarily for energy production. Excess levels of the “fuel” result in free-radical production.

Although it is somewhat counterintuitive, recent evidence suggests that there are more free radicals generated in vivo from trans and saturated fats than from unsaturated fats. One simplified way of thinking about it is that diets high in saturated fat or trans fat result in higher serum lipid levels. The longer residence time of blood lipids allows for oxidation of unsaturated fats in the blood lipids. The oxidized lipids result in high levels of free radicals, which trigger an inflammatory response.

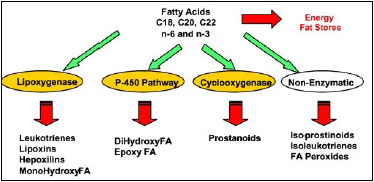

Similarly, excess levels of simple sugars can result in free radical formation at the cellular level. The free radicals from excess blood sugar, particularly in diabetics and pre-diabetics, are associated with increased levels of inflammation in cardiovascular tissue. When the body is not able to utilize glucose, aberrant oxidative path-ways take over.

There are two sources of chronic high blood glucose levels. First is insulin control. Whether not enough insulin is produced or the muscle cells have become insulin resistant, the result is the same: blood glucose levels remain high, and the excess glucose is metabolized to inflammatory free radicals (Brownlee, 2003).

The second source of excess glucose is constant intake. We have emerged as a society of constant eaters. One only needs to visit a mall or an amusement park and observe the number of individuals who are constantly eating. Unfortunately, many of these snacks have a very high glycemic value, so the blood glucose level never goes down to a fasting state. The result is that being overweight leads to insulin resistance and poor control of blood glucose levels. The excess blood sugar then produces free radicals, which leads to inflammation. Fig. 3 illustrates the side effects of hyperglycemia and the subsequent oxidative stress. Regardless of the cause of hyperglycemia, the results are likely to be negative (Rosen et al., 2003).

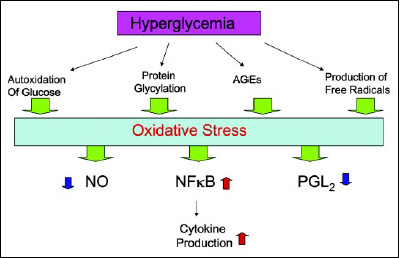

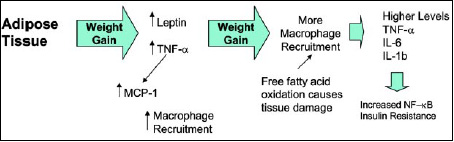

Excess body fat, particularly abdominal obesity, can also lead to chronic inflammatory conditions. Adipocytes, particularly those associated with central obesity, produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and IL-6 (Curat et al., 2004). As illustrated in Fig. 4, weight gain leads to more macrophage recruitment in the adipose tissue and associated inflammatory responses. The increased levels of inflammatory cytokines are then associated with higher levels of NF-kB and eventually insulin resistance. A convenient marker for these changes is circulating levels of C-reactive protein, CRP (Dandona et al., 2004). CRP is also a convenient marker for systemic inflammation, and in overweight or obese patients is a predictor of the metabolic syndrome and diabetes. This all supports the contention that chronic obesity can lead to chronic inflammatory symptoms and perpetrate the cascade of negative health effects (Beltowski et al., 2000).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Preventing Inflammation

Diet can have a significant impact on inflammation and may ultimately offer opportunity to control or delay the effects of chronic inflammation. A pro-inflammatory diet might be described as a diet in which high levels of saturated and trans fat are consumed or a hyperglycemic diet that results in high serum glucose levels through excess or constant consumption of high-glycemic foods. Either of these or the combination of the two can lead to excessive levels of free radicals being formed in vivo. These free radicals then trigger a chronic inflammatory response. Obesity can also increase chronic inflammation, because adipocytes produce cytokines, which trigger an inflammatory response.

There is an additional dietary factor, which significantly influences all of these pathways: the antioxidant level in the diet or in vivo. If we consider the pro-oxidative activity of simple sugars and saturated/trans fat and the lack of antioxidants, we see the profile of a diet that significantly increases the risk of inflammatory conditions.

Antioxidants in the diet have been shown to be remarkably effective in delaying or preventing the onset of chronic inflammatory diseases. For example, resveratrol from grapes has been shown to have remarkable biological actions which may be effective against cardiovascular disease, some forms of cancer, and arthritis. Subsequent research has shown that other phenolic antioxidants are remarkably powerful antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents. Many of the botanical extracts purported to have medical benefits may act as antioxidants and anti-inflammatories in vivo. Fig. 5 illustrates some of the inflammatory conditions that have been reported to be delayed or mediated by antioxidants.

Phenolic antioxidants work in a number of ways to reduce or prevent the development of inflammation. First, they act as antioxidants in the food and in vivo. Phenolics can act as free-radical scavengers, removing active oxygen species which can be initiators of chronic inflammation. In addition, some phenolics act as direct inhibitors of lipoxygenase or cyclooxygenases (particularly COX-2) to mediate the inflammatory response. Some of the phenolic compounds influence inflammation at different points in the inflammatory cascade by controlling gene expression.

The direct effects of individual compounds are now being unraveled in the literature. From a practical standpoint currently, it would seem judicious to consume a variety of foods that deliver multiple phenolic compounds. Several reports have suggested that mixed systems are more effective than individual materials.

Fruits and vegetables typically bring multiple benefits that would reduce the risk of chronic inflammation. They are lower in fat, particularly saturated fat, and essentially devoid of trans fats. Although fruits are associated with high sugar levels, they also contain fiber, which helps to control the uptake of simple sugars. Fruits and vegetables contain high levels of phenolic compounds and the antioxidant vitamins.

Unfortunately, history would suggest that there are many barriers to adequate fruit and vegetable consumption. Fresh fruits and vegetables can be relatively expensive, they are not convenient so as food preparation times have dropped vegetables have dropped by the wayside from meals. Perhaps one reason for poor consumption is that many people simply don’t like vegetables. Regardless of the reason, the bottom line is that as a society we don’t eat enough fruit and vegetable based foods.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Food Technology Can Help

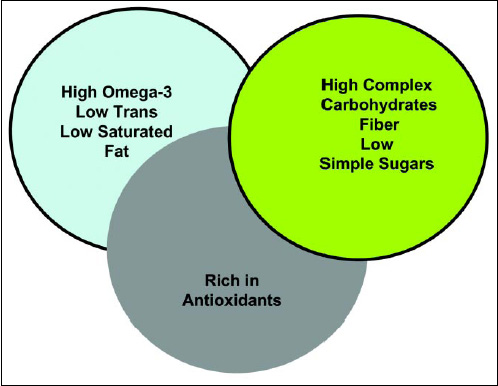

The food industry has an unprecedented opportunity to help the consumer by offering food choices that would support an anti-inflammatory diet. If we assume that the consumer is not going to make long-term dietary change overnight, we need to offer alternatives that help reduce the risk or consequences of being overweight and recognize consumers’ current profile of food choices. One alternative is to help facilitate an anti-inflammatory diet. Such a diet consists of three major features (Fig. 6).

The food industry is well on the path to offer foods that are low in saturated and trans fats. The more challenging opportunity is to develop foods that are rich in omega-3 fatty acids. There are clear challenges because of the inherent oxidative instability of the omega-3 fatty acids; however, the health benefits are very well documented. It also appears that the consumer recognizes the benefit of omega-3 fatty acids and are likely to be willing to pay a premium for such products.

The recent low-carbohydrate diet craze also may deliver considerable long-term benefit in terms of controlling chronic inflammation. There are emerging reports in the literature that low-carbohydrate diets result in lower CARP in many patients. Clearly, reducing simple carbohydrates in prepared foods and snack foods will help the consumer avoid the constant intake of high-carbohydrate foods, which will allow insulin recovery and delay the onset of insulin resistance.

The inclusion of more antioxidants in the diet is a new opportunity. While we have emphasized fruits and vegetables as sources of phenolic antioxidants, it is important to recognize that many of our favorite foods and beverages also contain substantial levels of antioxidants and anti-inflammatory phenolics. For example, cocoa is a rich source of antioxidants, and Masterfoods has established a Web site promoting its health benefits. Wine, beer, coffee, and tea are also rich in antioxidants.

Food technology can also provide the benefits of fruits and vegetables by including extracts or concentrates of phenolics in conventional foods. With all foods, taste is a prime driver in whether or not they will be consumed. Phenolic compounds frequently are bitter or astringent, overcoming the flavor issues associated with phenolic-based materials will offer the opportunity for creative food technology to deliver new foods with anti-inflammatory benefits. The growing awareness of consumers suggests that the market for such products will continue to grow.

by John W. Finley

The author, a Professional Member of IFT, is Chief Technology Officer, A.M. Todd Co., 150 Domorah Dr., Montgomeryville, PA 18936, [email protected].

References

Brownlee, M. 2003. A radical explanation for glucose-induced cell dysfunction. J. Clin. Invest. 112: 1788-1790.

Curat, C.A., Miranville, A., Sengenes, C., Diehl, M., Tonus, C., Busse, R., and Bouloumie, A. 2004. From blood monocytes to adipose tissue-resident macrophages: Induction of diapedesis by human mature adipocytes. Diabetes 53: 1285-1292.

Dandona, P., Aljada, A., and Bandyopadhyay, A. 2004. Inflammation: The link between insulin resistance, obesity and diabetes. Trends Immunol. 25: 4-7.

Pischon, T., Hankinson, S.E., Hotamisligil, G.S., Rifai, N., Willett, W.C., and Rimm, E.B. 2003. Habitual dietary intake of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids in relation to inflammatory markers among US men and women. Circulation 108(2): 155-160.

Rosen, P., Nawroth, P.P., King, G., Moller, W., Tritschler, H.-J., and Packer, L. 2001. The role of oxidative stress in the onset and progression of diabetes and its complications: A summary of a congress series sponsored by UNESCO-MCBN, the American Diabetes Association and the German diabetes society. Diabetes/Metabolism Res. Rev. 17(3): 189-212.