What is Natural?

Despite attempts by regulatory agencies to set parameters, developing and marketing products with ‘natural’ label claims can be a tricky proposition.

Food marketers face consistent pressure to find ways to differentiate their products from those of their competitors. "Natural" claims are a tempting way to do so, given the premium placed on natural products by consumers. Correctly or incorrectly, consumers perceive that natural products are better for them and for the environment. However, developing and marketing products that satisfy this consumer preference is made difficult by the lack of clarity and consistency as to just which types of ingredients and processes are compatible with use of a natural claim.

Industry interest in this issue prompted the IFT Food Laws and Regulations Div. to develop a symposium and round-table titled "What Is Natural?" for the 2008 Annual Meeting in New Orleans, La., this past July. (The events were co-sponsored by the Food Chemistry Div.) In order to have government as well as industry input and interaction, two sessions were developed. The first was a symposium to provide a balanced view of the current state of U.S. regulations, with a speaker each from the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture (USDA), and a food industry trade group, the Grocery Manufacturers of America (GMA). The symposium attracted more than 300 attendees. The second session consisted of concurrent roundtable sessions in which participants engaged in lively discussions of different aspects of the issue.

Industry interest in this issue prompted the IFT Food Laws and Regulations Div. to develop a symposium and round-table titled "What Is Natural?" for the 2008 Annual Meeting in New Orleans, La., this past July. (The events were co-sponsored by the Food Chemistry Div.) In order to have government as well as industry input and interaction, two sessions were developed. The first was a symposium to provide a balanced view of the current state of U.S. regulations, with a speaker each from the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture (USDA), and a food industry trade group, the Grocery Manufacturers of America (GMA). The symposium attracted more than 300 attendees. The second session consisted of concurrent roundtable sessions in which participants engaged in lively discussions of different aspects of the issue.

In September, many of the speakers and facilitators from the Annual Meeting symposium and roundtable participated in an IFT Webcast titled "What Is Natural?" to reach out to food industry members who could not attend the Annual Meeting event. That Webcast was the largest ever hosted by IFT, with 132 registered sites. A few days before the Webcast, an Internet survey was sent out to all registrants. The survey garnered an impressive 53% response rate, and the results were discussed during the Webcast.

This article tries to capture the essence of the symposium, round-table discussions, and subsequent Webcast and survey to help foster greater understanding and further discussion of this important issue. The Webcast survey suggests that, although there is agreement in the food industry on some aspects of the use of the claim "natural," there is a lack of consensus on many other aspects. We hope that this article will help serve as a spring-board for any subsequent efforts to elaborate on circumstances under which it is appropriate to use the claim natural to describe particular ingredients and processes.

A Historical Perspective

From a historical point of view, the industrial revolution transformed the food supply in the 20th century from dependence on locally produced fruits and vegetables and meats processed at home to reliance on complex industrial giants making processed foods using numerous ingredients from a variety of sources. During the second half of the 20th century, chemistry gained a bad name with many consumers as connections were drawn between some chemicals and various forms of pollution that threatened to diminish quality of life. Also, as human lifespan increased and medical advances largely eliminated many childhood diseases, medical researchers and consumers focused more on diseases that emerge in old age, especially cancer. Concerns about possible links between consumption of certain chemicals and cancer gave rise to inclusion of the Delaney Clause in the 1958 Food Additives Amendment to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. The Delaney Clause, which is still in effect, prohibits FDA from approving any food additive found to induce cancer in humans or animals.

In the late 1960s, counter-cultures emerged wanting to go back to simpler times, and they began to lay the foundation for the organic movement. Many consumers came to have strong reservations about the use of certain chemicals and processing techniques in the manufacture of food.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

In the 1970s, FDA (which has jurisdiction over all foods except for meat, poultry, and egg products) issued new regulations defining "natural flavor" and requiring the presence of color from natural sources be declared so that consumers could make more informed decisions about the foods that they purchased (21 CFR section 101.22). In 1988, FDA informally defined natural to mean that nothing artificial or synthetic has been included in or added to a food that would not normally be expected to be in the food.

In 1991, FDA voiced its concern over evidence indicating that natural was used on a variety of products to mean a variety of things (Federal Register, 1991). FDA reviewed definitions used by other government agencies, state governments, and industry and concluded that additional consumer and industry input was needed. A wide range of comments was submitted to FDA. In 1993, FDA announced its decision not to define the term natural by regulation due to limited resources and other priorities. However, FDA retained its policy on natural that it had articulated in 1988, and that policy remains in effect (Federal Register, 1993). CFSAN continues to apply the policy on a case-by-case basis in response to inquiries or complaints from industry.

In the interim, USDA (which has jurisdiction over meat, poultry, and egg products) issued an FSIS Policy Memo that defined natural via a decision tree containing the following two questions: (1) Does the product contain an artificial flavor/flavoring, a coloring ingredient, a chemical preservative, or any other synthetic or artificial ingredient? (If yes, then the product is not natural.) (2) Are the product and its ingredients only minimally processed? (If yes, then the product is natural.) FSIS’s policy thus differs somewhat from FDA’s in that it explicitly takes into account the extent of processing of a product. Like CFSAN, FSIS applies its policy on a case-by-case basis. However, unlike CFSAN, FSIS reviews and approves product labeling, including use of the claim natural, prior to marketing.

An additional potential source of confusion stems from the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service’s relatively recent issuance of regulations and promulgation of standards that are tangentially related to the question of what natural means. The most significant of these are the National Organic Program regulations, which establish which substances and processes are permissible in the production of foods labeled as "organic," and the standard that defines what it means for livestock to be "naturally raised."

Finally, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which exercises jurisdiction over deceptive and unfair food advertising, decided against defining natural by regulation in the early 1980s. Since then, FTC has taken little action on the issue. However, as discussed further below, the same can not be said of the National Advertising Div. (NAD) of the Council of Better Business Bureaus, a self-regulatory dispute resolution forum that investigates, and entertains challenges to, advertising practices alleged to be deceptive or unfair. NAD takes the view that the meaning of the term natural to consumers depends on a number of factors, including, but not limited to: a) the origin of the ingredients; b) how the term natural is presented in the context of the challenged advertising; and c) reasonable consumer expectation as to the meaning of the term.

Conflict and Controversy

The regulatory landscape on natural remained relatively quiet until August 2005, when FSIS decided to allow the use of certain levels of sodium lactate derived from a corn source in natural products. The following year, FSIS was petitioned to define natural by regulation to exclude the use of sodium lactate. In response, FSIS rescinded its prior decision on sodium lactate, and announced that it would define natural by regulation (Federal Register, 2006). Shortly thereafter, FSIS was strongly criticized for permitting poultry injected with certain solutions to be labeled as natural. FSIS has since been formally petitioned to prohibit that practice.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Meanwhile, the Sugar Assn. petitioned FDA to define natural by regulation to exclude high fructose corn syrup (HFCS), a request that was strenuously opposed by the Corn Products Assn. Sara Lee Corp. submitted a separate petition asking FDA to collaborate with USDA to establish a single definition of natural by regulation. FDA is unlikely to grant either of these petitions. Because FDA does not review and approve product labeling prior to marketing, FDA has little incentive to expend the resources that defining natural by regulation would consume.

Recently, FDA has been stung by controversy over its application of its policy on natural. In June 2008, FDA informally responded to a request submitted by a trade publication as to whether use of HFCS was consistent with use of the claim natural. FDA’s initial response was in the negative, based on the conclusion that the use of synthetic fixative in the active enzyme that is used to produce HFCS "would not be consistent with" FDA’s policy on natural claims. Then on July 3, 2008, FDA issued a letter of clarification to the Corn Refiners Assn. after the agency had the opportunity to consider new information that explained why, under certain methods of production, the synthetic fixative for the active enzyme is not included in or added to HFCS. FDA stated that it would not object to use of a natural claim on a product containing HFCS if the HFCS is manufactured in such a way that the synthetic fixative "does not come into contact with" the high dextrose equivalent corn starch hydrolysate substrate used to produce the HFCS. However, FDA made clear that it would object to the use of a natural claim if the HFCS has a synthetic fixative included in or added to it, or if the acids used to obtain the substrate are not consistent with FDA’s policy on natural. Unfortunately, the clarification was issued after the IFT Annual Meeting, and thus there was no opportunity to discuss the implications of FDA’s updated position on HFCS with IFT members.

As for NAD, it has been actively considering challenges to the use of natural claims in food advertising. For example, in 2006, NAD recommended against use of natural and "natural sweetener" in reference to a sweetening product that contains an artificial sweetener. And in 2008, NAD did not object to use of natural in relation to baby food to which vitamin C was added, but recommended against use of "all-natural" to describe that product. It seems likely that challenges will continue to be brought as long as there continues to be a lack of clarity on the meaning and scope of natural.

Public interest groups and individual consumers have also gotten in on the act. Perhaps the best known of these actions was the lawsuit filed by the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) against certain beverage manufacturers over their use of natural in the labeling of products that contained HFCS. CSPI succeeded in getting those manufacturers to stop using the claim natural, but given FDA’s recent pronouncement on HFCS, CSPI’s victory would appear to be short-lived. More recently, CSPI filed a citizen petition asking FDA to prohibit the use of artificial colors in food. The petition was triggered by a study conducted in the UK that suggests a link between Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in children and consumption of certain preservatives and certified color additives. The petition may actually include within its scope color additives not subject to certification because of the regulatory definitions applicable to color additives. Also troubling is a recent lawsuit filed by a consumer that alleged consumer fraud in the labeling of a product labeled as natural. Although that lawsuit was dismissed, the possibility remains that more such lawsuits will be brought.

Building Greater Consensus

Most participants in the round-table session at the IFT Annual Meeting expressed the view that the food industry should come to a consensus on a definition of natural so that the ingredients that are allowed or disallowed in products labeled as natural do not keep shifting. Since the food industry has the capacity to self-regulate up and down the supply chain, establishing firm criteria for each ingredient/product type could help provide welcome stability.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

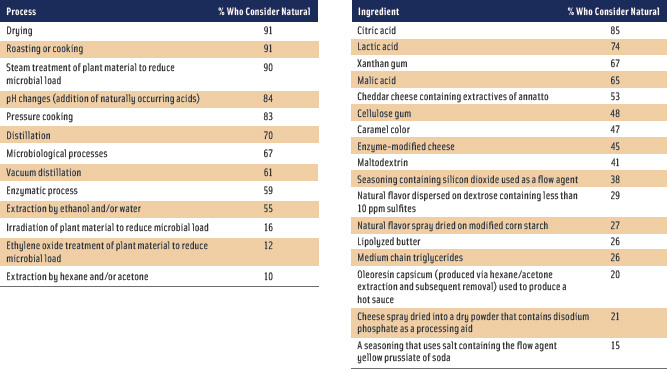

At this point, as the survey conducted among IFT "What Is Natural?" Webcast participants underscored, confusion—not clarity—is the rule among many industry members. Survey responses helped to reveal where much of this confusion about what is natural lies, but also where there could be some measure of agreement on the topic. Respondents provided insights into key areas, including the following. (See Table 1).

• Treatment of agricultural products. In terms of agricultural product treatments to reduce microbial loads, survey respondents agreed that only steam sterilization (90%) is natural, whereas irradiation (16%) and ethylene oxide gas (12%) treatments are not.

• Processes familiar to consumers. Another area of consensus among survey respondents is that processes familiar to consumers that can be performed at home are generally considered natural. These include drying (91%), roasting or cooking (91%), pH changes (addition of naturally occurring acids) (84%), and pressure cooking (83%).

• Traditional processes. Survey respondents were less certain about traditional processes such as distillation (addition of heat causing a separation) (70%), vacuum distillation (addition of heat while removing pressure causing a separation) (61%), enzymatic (59%) and microbiological (67%) processes, and extraction by ethanol/water (55%). However, survey respondents were fairly certain that extraction by hexane/acetone (10%) is not natural as this process is not accepted by the organic regulations. This was further confirmed by the survey results for the ingredient oleoresin capsicum used to produce a hot sauce (20%), even though this flavor is considered natural per the FDA regulation at 21 CFR section 101.22.

Another contradiction that appeared in the survey was the fact that enzymatic and microbiological processes were generally considered natural, but survey respondents were much less certain with respect to ingredients made by these processes such as enzyme modified cheese (45%) and lipolyzed butter (26%). Could it be that the food industry believes that any name unfamiliar to the consumer needs to be considered not natural? Another example of this was the low score given to medium chain triglycerides (26%), which is simply fractionated coconut and/or palm kernel oil.

• Ingredients. Malto-dextrin (41%) is another ingredient where the food industry appears to be very confused about whether it is natural. This ubiquitous carrier or bulking agent, according to the FDA regulation at 21 CFR section 184.1444, can be produced either via acid, acid-enzyme, or enzyme-enzyme hydrolysis of cornstarch; both acid and enzyme processes were generally considered natural by the same people in the survey. For those survey respondents who did not consider maltodextrin to be natural, could it be that they believe that the pH change was produced by a strong inorganic acid rather than by a weaker organic acid, and therefore that difference makes it not natural? Or could it be due to the fact that most corn is processed using sulfur dioxide to soften the kernels as the first step in the process? However, if that were the case, then most food products generated from corn starch could be suspect for being not natural. Are they? We know that native corn starch is derived from a natural source, but is it natural?

Flow agents are another area where there appears to be much confusion in the food industry. Survey respondents generally did not view silicon dioxide (38%) or yellow prussiate of soda (15%) as natural. Does that mean any use of flow agents in dry products makes those products not natural? Or might there be some flow agents that could be considered natural?

Moving Forward

The lack of understanding and agreement within industry poses more of a problem for FDA-regulated products than for USDA-regulated products because of the fact that labeling of FDA-regulated products is not subject to FDA premarket review. The recent controversy over HFCS is likely to give pause to anyone thinking of contacting FDA as to whether use of a given ingredient is compatible with use of a natural claim. This means that, in the absence of a regulation or guidance from FDA that addresses the issue, manufacturers are likely to continue to make their own decisions case-by-case, and to take their chances with competitors, consumer watchdogs, and plaintiff’s lawyers .

If there is no realistic possibility that a single definition of natural will be established in the near future, there are numerous reasons to try to work toward greater consistency and predictability with respect to the use of natural claims. First, there are the uncertainties and expenses associated with the types of regulatory and legal actions described above. Second, there is the possibility that consumers could begin to lose confidence in the value of natural claims, potentially killing the goose that has been laying such golden eggs. Third, it is likely that there are hidden costs to the ongoing controversy. For example, many of the food companies that are devising their own criteria for natural are attempting to learn intimate details of how ingredients are produced from their vendors and their vendors’ vendors so that they can make informed decisions, instead of simply reacting to an ingredient name that may sound like a product of advanced chemistry.

However, these questionnaires up and down the supply chain are asking, in many cases, for proprietary information that would never have been shared in the past. This places vendors in the uncomfortable position of either disclosing proprietary information or risking the loss of business. This tension could at least be reduced if there is greater understanding and agreement as to when use of a natural claim is appropriate.

Carolyn Fisher , Ph.D., a Professional Member of IFT, is Quality Assurance Regulatory Manager, McCormick & Co., 226 Schilling Circle, Hunt Valley, MD 21031 ( [email protected] ). Ricardo Carvajal, J.D., M.S., a Member of IFT, is Of Counsel with Hyman, Phelps & McNamara, P.C., 700 13th Street, NW, Suite 1200, Washington, D.C. 20005 ( [email protected] ).

References

FDA. 21 CFR section 101.22.

FDA. 21 CFR section 184.1444.

Federal Register 56 (Nov. 27, 1991), p. 60466.

Federal Register 58 (Jan. 6, 1993), p. 2407.

Federal Register 71 (Dec. 5, 2006), p. 70503.