Getting Crisis Communication Right

Eleven best practices for effective risk communication can help an organization navigate the slippery path through a crisis situation.

Responding effectively and appropriately when a crisis strikes isn’t necessarily something that comes naturally, even within a well-run organization. It requires a carefully considered, ready-to-implement plan, built on a framework of responsible, ethical industry best practices.

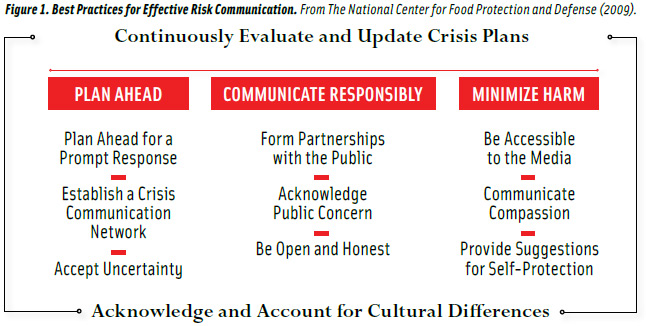

The National Center for Food Protection and Defense (NCFPD), a Center of Excellence sponsored by the Department of Homeland Security, has developed a set of 11 best practices for effective risk communication. Initially identified through an exhaustive review of the risk communication literature, these 11 best practices are designed to assist organizations and agencies in developing crisis communication plans and for responding to recalls and similar crisis situations. In the past four years, the Risk Communication Team within the NCFPD has conducted a series of case studies and message testing experiments to clarify, validate, and refine the best practices.

Nine of the best practices focus on planning, communicating responsibly, and minimizing harm. Two are ongoing and should be considered in all risk messages.

Plan Ahead

The first best practices section focuses on strategic planning. The goal in strategic planning is to prepare the organization for a prompt response to a crisis event. We do not see this pre-planning as pessimistic. Rather, planning ahead takes into account the fact that the food system’s complexity puts all related organizations at risk. Strategic planning, then, anticipates which resources and communication contacts will be needed in the event of a crisis. Naturally, the initial goal is to avoid a crisis altogether. When such avoidance is impossible, however, planning head assures organizations their response will maximize all opportunities available for minimizing the impact of the crisis.

1 Prompt response

In the planning ahead category, the first best practice is a prompt response. Organizations should develop a plan for immediate access to the resources needed for a swift response to a crisis situation. Resources may be physical, such as emergency response crews and equipment or warning and evacuation systems. For food producers and processers, a rapid response is also clerical in nature. Detailed records of what was produced, when it was produced, and where it was shipped are essential for an immediate and meaningful response to a crisis.

2 Establish a crisis communication network

A crisis communication network is based on three general lines of communication. First, communication within the organization should allow for a rapid report of any irregularities, particularly when they have the potential to create a crisis situation. If an organization maintains open lines of communication among all levels of the organization, information can be shared quickly and accurately. This form of communication includes the capacity to quickly share information with all stakeholders, ranging from employees to suppliers. Second, organizations must communicate consistently and frankly with regulatory agencies. Maintaining compliance with all industry standards and establishing familiarity with agency representatives are helpful in both avoiding and responding to a crisis situation. Third, establishing a positive relationship with the media prior to a crisis event can help organizations develop the type of credibility and familiarity needed to share information rapidly with consumers.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

3 Accept uncertainty

Crisis situations are distinct from other issues organizations are forced to manage. Specifically, crises have three consistent characteristics: threat, surprise, and short response time (Hermann, 1963; Ulmer et al., 2007). Crises pose a threat to lives or livelihoods, they come as a surprise with little or no observed warning, and without immediate action, the situation will steadily worsen. Thus, organizations must respond quickly to threatening situations while still reeling from the shock of the event. In doing so, organizations must recognize and honestly communicate that they are taking action even though they do not have a complete understanding of the event. The standard recommendation is that organizations tell the public what the organizations know, admit what they do not know, and explain what they are doing to gather additional information.

Communicate Responsibly

The second set of best practices focuses on communicating responsibly before, during, and after a crisis event. In the most general sense, responsible communication is based on a dedication to making the best information available to all parties who need the information for making decisions about their safety and well-being. The following three best practices focus on establishing a record of responsible communication.

4 Form partnerships with the public

Seeking opinions from the public through dialogue about risk issues is an essential step in forming a collaborative partnership with the public. The trust emerging from an organization’s or agency’s partnership with the public affords a level of credibility that thereby fosters public responsiveness in the wake of a crisis. The ultimate advantage of such a partnership is that the public can serve as a resource, rather than a burden, in risk and crisis situations. Organizations that fail to engage the public in a dialogue focusing on risk issues place themselves at an extreme disadvantage when crises strike.

5 Acknowledge public concern

Related to forming partnerships with the public is the need to openly acknowledge public concerns. Sandman (1993) explains that, regardless of the organization’s opinion, responding to the public’s perceptions of risk is absolutely essential. Sandman contrasts the hazard, the scientific evidence of risk, with the outrage, the public’s perception of risk. If outrage is high but the hazard is low, organizations are wise to communicate with the public in a way that acknowledges their fears. Conversely, if the hazard is high and the public outrage is low, organizations are expected to provide the public with adequate messages warning of possible harm.

6 Be open and honest

There is no substitute for the truth in risk and crisis communication. A vigilant media will, eventually if not immediately, reveal any intentional deception, fabrication, or falsehood offered by the organization before or during a crisis. Similarly, responding with answers such as “no comment” or avoiding any interaction with the public or press reveals a cavalier attitude and implies guilt. Moreover, organizations engaging in deception or stonewalling are more likely to create a second crisis for themselves through the revelation of a conspiracy or cover-up. Simply put, being open and honest is an essential dimension of responsible communication.

Minimize Harm

The NCFPD firmly adheres to the philosophy that effective risk and crisis communication can actually minimize harm and save lives. To that end, the center has developed three best practices that focus on emergency communication during the acute phase of a crisis event.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

7 Be accessible to the media

Those organizations that cultivate a contentious relationship with the media harm both themselves and the general public. The media offers, by far, the most proficient and rapid means of sharing risk and crisis messages with the public. No other channel of communication has the reach and resources to immediately alert the public of a threatening situation. Organizations that avoid, debate, or attempt to deceive the media render this potential, at least momentarily, ineffectual. Those who remain accessible to the media have the potential outcome of allowing the media to serve as a resource for public well-being.

8 Communicate compassion

By their nature, crises are threatening and harmful. Those who fall victim to crises are often dealing with financial loss, injury, or are grieving the loss of loved ones. Any message shared by an organization must take into account the feelings of anguish, anxiety, and despair that message recipients are feeling. Communicators should acknowledge their listeners’ and readers’ emotions and communicate empathetically. Communicating with genuine compassion can help to maintain the public’s trust and attention, both of which are essential for minimizing harm and beginning the recovery process.

9 Provide suggestions for self-protection

The public can often take precautionary steps to avert harm during a crisis. Recalling contaminated food products, for example, can reduce the number of individuals infected by the product. Similarly, recommendations to boil drinking water or to completely avoid some produce from a particular region of the country can save lives. Even if definite information is not available for self-protection, organizations are advised to make reasonable recommendations. Such suggestions alleviate the potential for members of the public to harbor feelings of utter helplessness as a crisis runs its course.

Ongoing Strategies

The final two best practices pervade the nine discussed above. Organizations and agencies should consider each of these best practices in all risk and crisis communication decisions they make.

10 Continuously evaluate and update crisis plans

Like any planning process, crisis plans and risk communication strategies must evolve with time. Sadly, some organizations have crisis plans on their office shelves that have not been reviewed for months or years. Risk and crisis planning and assessment must keep pace with the rapidly changing environment on the local, national, and global levels.

11 Acknowledge and account for cultural differences

Standard communication forms, including the media, are unlikely to reach underrepresented populations—new Americans and those enduring poverty, among others. These individuals have inadequate access to or a lack of trust in standard messages such as news releases and mainstream media sources (Sellnow et al., 2009). Organizations and agencies must make concerted and ongoing efforts to develop expansive networks that include community leaders and media sources dedicated to reaching the populations described above. Failure to do so increases the potential harm to thousands of citizens.

Best Practices in a Complex Food Supply Chain

While we believe the best practices outlined here are essential for crisis planning and response, we also realize that their application to crisis events is often hampered by the food supply chain’s complexity and the ethical lapses of those in decision-making positions within the system. Two recent cases accentuate this point: Salmonella-tainted peanut butter from Peanut Corporation of America (PCA) and milk products containing melamine from Sanlu Group in China.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

When an inordinate number of Chinese babies developed life-threatening kidney problems in the summer of 2008, an investigation revealed the Sanlu brand of milk formula they had been given was contaminated with dangerous levels of melamine. In this case, melamine was intentionally added to milk products to raise protein levels. Worldwide, hundreds of Chinese products were recalled as the extent of the contamination became known.

An eerily similar case developed in the United States when PCA officials knowingly distributed Salmonella Typhimurium contaminated peanut butter to numerous institutions and food processors. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicates that at least 714 reported illnesses are linked to this particular foodborne outbreak (CDC, 2009). USA Today reported more than 3,600 products were recalled between January and April (Schmit, 2009).

The widening ramifications in both cases reveal how the food supply chain’s complexity and interconnectivity immensely compound this type of corruption’s impact. Deceptive and intentional violations of safety standards reflect a blatant disregard for all of the best practices for risk and crisis communication.

Beyond recognizing a need for closer inspection and oversight, little can be learned from those Sanlu and PCA officials who engaged in criminal behavior. Much can be learned, however, from the reactions of organizations whose products were or might have been contaminated as a result of Sanlu’s and PCA’s actions. Initial claims or assumptions that tainted milk products were largely limited to China were proven inaccurate as ongoing investigations revealed the presence of melamine, albeit small amounts, in a number of products in the human food supply chain.

Some of Cadbury’s products, for example, had to be recalled because they were tainted with melamine. Similarly, the Hershey Creamery Co. (no affiliation with Hershey, Pa.-based The Hershey Co.) initially claimed it did not purchase peanut butter from PCA, yet one of the company’s ice cream products later appeared on the FDA peanut butter products recall list. The point here is that immediate and explicit claims of complete product safety were proven false as the investigations continued. In both crises, the need to accept uncertainty was made clear. Accepting uncertainty and communicating more cautiously during a recall and investigation can help organizations avoid losses in credibility caused by over-reassuring the public.

Despite the failings of Sanlu and PCA, many companies affected by the tainted products communicated admirably. For example, Martin Kanan, King Nut Co. President, communicated openly, honestly, and with compassion as he cooperated with the media to express his remorse and to recall King Nut products. In a press release, Kanan said, “We are sorry this happened” and “We are taking immediate and voluntary action because the health and safety of those who use our products is always our highest priority” (King Nut Co., 2009).

The melamine and peanut butter cases have also accentuated the need for clear communication networks among agencies and organizations. For example, Fonterra, the New Zealand based company linked to Sanlu, met with frustration when it initially argued that Sanlu should immediately recall the tainted product. Similarly, PCA was evasive when signs of contamination began to surface in its products and in the products of companies to which they had supplied peanut butter.

The recent response of Stephen Sundlof, Director of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, gives cause for optimism in this area. In February, Sundlof stated:

“FDA is working hard to ensure the safety of food, in collaboration with its federal, state, local, and international food safety partners, and with industry, consumers, and academia. Although the Salmonella Typhimurium foodborne illness outbreak underscores the challenges we face, the American food supply continues to be among the safest in the world. Food safety is a priority for the new Administration” (Sundlof, 2009).

The partnerships Sundlof mentions are essential for meeting the demands of the best practices for risk and crisis communication.

Clearly, the tainted milk and peanut butter cases illustrate the extensive harm that arises when food suppliers and processors fail to plan for crises, communicate dishonestly, ignore public concerns for food safety, and attempt to deceive or ignore the media. We learn from our success and failures to make good use of these best practices.

Timothy Sellnow, Ph.D., is Associate Dean for Graduate Programs, College of Communications and Information Studies, University of Kentucky, 133 Grehan Building, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506 ([email protected]). Kathleen Vidoloff is a Doctoral Student, Department of Communication, University of Kentucky, 124 Grehan Building, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506 ([email protected]).

References

CDC. 2009. Investigation update: Outbreak of Salmonella Typhimurium Infections, 2008-2009. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, April 29. http://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/. Accessed Aug. 21, 2009.

Hermann, C.F. 1963. Some consequences of crisis which limit the viability of organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly 8(1): 61-82.

King Nut Co. 2009. King Nut issues peanut butter recall. Press release, Jan. 10. http://www.kingnut.com/site.cfm/news.cfm. Accessed March 4, 2009.

Sandman, P.M. 1993. Responding to community outrage: Strategies for effective risk communication. American Industrial Hygiene Assn., Fairfax, Va.

Schmidt, J. 2009. Broken system hid peanut plants’ risks; case reveals every link in food-safety chain failed. USA Today, April 27, B1.

Sellnow, T.L., Ulmer, R.R., Seeger, M.W., and Littlefield, R.S. 2009. “Effective Risk Communication: A Message-Centered Approach.” Springer Science+Business Media LLC, New York.

Sundlof, S. 2009. Statement of Stephen F. Sundlof, D.V.M., Ph.D. Testimony Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations Committee on Energy and Commerce U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, D.C. http://www.fda.gov/ola/2009/salmonella021109.html. Accessed March 4, 2009.

Ulmer, R.R., Sellnow, T.L., and Seeger, M.W. 2007. “Effective Risk Communication: Moving from Crisis to Opportunity.” Sage, Thousand Oaks, Calif.