Fighting Food Fraud

FOOD SAFETY & QUALITY

Foods and food ingredients can be adulterated both intentionally and unintentionally. In its efforts to protect the food supply, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) undertakes both food defense and food safety activities. Food defense is the effort to protect the food supply against intentional contamination due to sabotage, terrorism, counterfeiting, or other illegal, intentionally harmful means. Potential contaminants include biological, chemical, and radiological hazards that are generally not found in foods or their production environment. Food safety is the effort to prevent unintentional contamination of food products by agents reasonably likely to occur in the food supply, such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Listeria. Another form of adulteration is economically motivated adulteration (EMA), which is fraud carried out for financial gain. Although it may not be intended to cause safety problems, EMA also has the potential to cause harm.

USP Addresses Economic Fraud

On November 17, 2014, the U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention (USP), Rockville, Md. (www.usp.org), issued a proposed document, “Guidance on Food Fraud Mitigation,” as a framework for the food industry and regulators to develop and implement preventive management systems to deal with EMA of food ingredients. A nonprofit scientific organization that develops standards to help ensure the identity, quality, and purity of food ingredients, dietary supplements, and pharmaceuticals, the USP publishes its food ingredient standards in the Food Chemicals Codex (FCC).

Jeff Moore, senior scientific liaison, USP, said that the USP’s expert panel on food adulteration spent one year discussing which problems the document would address and one year writing it. The proposed guidance document is available on the FCC website and is open for public comment until March 31, 2015. Moore said that the comments received and the expert panel’s response to them will be posted online this summer. If the committee needs more time to evaluate the comments or requests additional information, the comment period may be extended. The finalized document is scheduled to be published in appendix XVII to the third supplement of the ninth edition of the FCC on September 1, 2015. Calling it a first-of-its-kind guidance document dealing specifically with EMA of food ingredients, Moore said that it is intended to help users develop a fraud management system that prioritizes and focuses mitigation resources on ingredients that not only carry the most vulnerability but also have potential for detrimental consequences when fraud occurs.

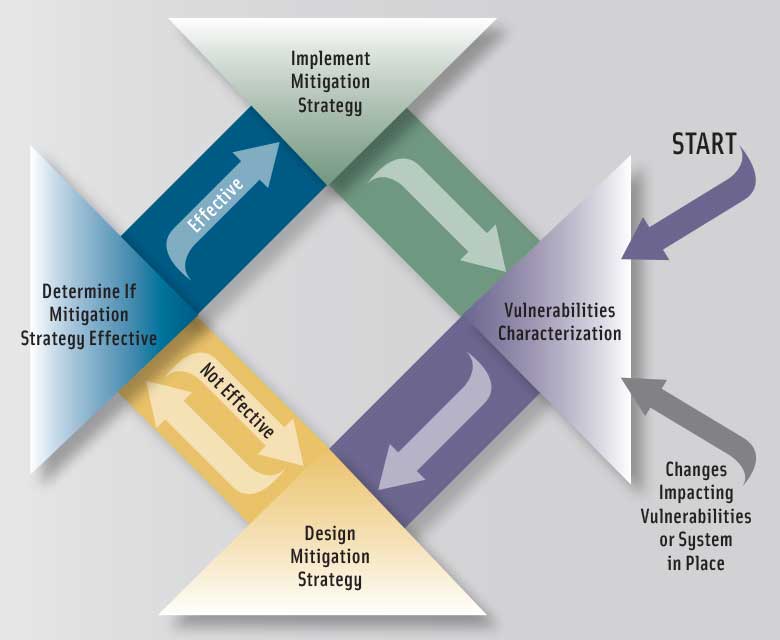

The approach consists of four steps. The first three characterize the overall fraud vulnerabilities of an ingredient by assessing factors contributing to fraud occurrence and the potential public health and economic impacts when fraud does occur, and the fourth provides guidance on how to use information from the first three steps to develop a mitigation strategy. The document describes the factors to be considered in each step and provides in-depth discussions of actual fraud cases to illustrate the value of assessing the impact of those factors. The first step is to conduct a vulnerability assessment addressing the following factors:

• Supply chain. A food ingredient’s vulnerability to fraud increases with the complexity of the supply chain. The lowest vulnerability is when a single-ingredient food is sourced directly from a trusted supplier who in turn sources from a trusted supplier. The highest vulnerability is when ingredients are sourced from multiple sources in an open market where there is limited knowledge about the supplier and when the ingredient is handled by multiple parties and the source identity is lost or not actively tracked, as when ingredients are blended. An example is the supply chain aspects of the melamine-tainted pet food incident, which involved the addition of low-purity melamine to inferior grade wheat gluten and other protein-rich ingredients to boost the apparent protein content.

• Audit strategy. The vulnerability of a supply chain to food fraud depends on the auditor’s qualifications, the type of audit (onsite or other), inclusion of anti-fraud elements in audits, who conducts the audit (the ingredient customer, the supplier, or an independent third party), the frequency of onsite auditing, and the use of unannounced audits. An example is an incident involving the marketing of frozen unsweetened orange juice concentrate that was adulterated with beet sugar using a cleverly designed manufacturing facility to conceal the fraudulent practices. It illustrates the extent of deception used to hide fraudulent practices and thereby the strengths and weaknesses of different audit strategies as a way to prevent fraud.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Supplier relationship. The vulnerability of ingredients to food fraud ranges from low for a trusted supplier to high for a new supplier with whom no relationship has been established. For example, a brand of apple juice for infants was marketed and labeled as pure apple juice but contained water, beet sugar, cane sugar syrup, corn syrup, water, malic acid, artificial coloring, and artificial flavoring.

• Supplier relationship. The vulnerability of ingredients to food fraud ranges from low for a trusted supplier to high for a new supplier with whom no relationship has been established. For example, a brand of apple juice for infants was marketed and labeled as pure apple juice but contained water, beet sugar, cane sugar syrup, corn syrup, water, malic acid, artificial coloring, and artificial flavoring.

• History of supplier quality and safety issues. This factor estimates the vulnerability to fraud due to the lack of sufficient controls by a supplier. For example, although Salmonella was not intentionally introduced into certain peanut products, company executives knew about the contamination but sold the products anyway.

• Susceptibility of quality assurance methods and specifications. This factor describes the vulnerability based on a lack of sufficient analytical methods and specifications. One example is whey protein ingredients, for which the lack of selectivity and specificity of the Kjeldahl nitrogen method for protein nitrogen dramatically increases the vulnerability. Another example is a fruit juice concentrate purchased on the basis of methods and specifications for only Brix, pH, and visual color.

• Testing frequency. This factor describes the vulnerability based on a lack of sufficient testing frequency.

• Fraud history. This factor characterizes the potential for fraud in an ingredient, based on the pattern and history of reported fraud issues. Examples are adulteration of milk, for which criminals constantly develop new ways to circumvent the latest adulteration detection methods; cassia oil, which is prone to adulteration even when new detection methods are developed; and a false report that street vendors in China were selling pork dumplings containing cardboard. The examples illustrate how combining the information in the USP’s Food Fraud Database (www.foodfraud.org) and the National Center for Food Protection and Defense’s EMA Incidents Database (www.FoodShield.org) for a particular ingredient can provide insight into the history of food fraud.

• Geopolitical considerations. This factor describes the vulnerability based on a lack of food control, regulatory, and other geopolitical factors that ensure food safety and prevent food fraud in any region of the world. The factor is integrally tied to the number of raw materials used to produce the finished ingredient, the geographic sources of the ingredients, and the number of geographic regions through which the ingredients and components of ingredients may transit. For example, chili powder from India was adulterated with the suspected carcinogen Sudan I dye and was found in Worcestershire sauce in the United Kingdom.

• Economic anomalies. This factor describes the vulnerability of ingredients to food fraud based on economic anomalies occurring in the marketplace. An example is the spike in price of vanilla, the second most-expensive spice (saffron is the first), caused by extreme weather conditions and increasing consumer demand for natural vanilla instead of synthetic vanilla as well as analytical difficulties to authenticate vanilla due to its complex and variable composition and challenges of available analytical methods.

The second step is to assess the potential food safety/public health and economic impacts of fraud. The traditional food safety risks associated with food fraud where the adulterant has the potential to cause illness or death are the most obvious public health impact concerns. While those who commit EMA do not intend to cause illness or death, they do not always understand the potential harmful effects of the adulterating material. Melamine adulteration of dairy proteins, denatured rapeseed oil adulteration of olive oil, and methanol contamination of vodka are examples. The adulteration of foods that constitute the major, sole, or necessary component of a diet substantially raises the potential public health impact. Pet food, infant formula, and baby food are examples as are foods that provide baseline nutrition for a sub-population. The loss of consumer confidence illustrates that damage to a brand can be expensive and long-lasting.

The second step is to assess the potential food safety/public health and economic impacts of fraud. The traditional food safety risks associated with food fraud where the adulterant has the potential to cause illness or death are the most obvious public health impact concerns. While those who commit EMA do not intend to cause illness or death, they do not always understand the potential harmful effects of the adulterating material. Melamine adulteration of dairy proteins, denatured rapeseed oil adulteration of olive oil, and methanol contamination of vodka are examples. The adulteration of foods that constitute the major, sole, or necessary component of a diet substantially raises the potential public health impact. Pet food, infant formula, and baby food are examples as are foods that provide baseline nutrition for a sub-population. The loss of consumer confidence illustrates that damage to a brand can be expensive and long-lasting.

The third step is to combine steps one and two to generate an overall characterization of vulnerabilities. And the fourth step is to develop an appropriate mitigation strategy with three possible outcomes: 1) “new controls are optional,” in which a user can decide that documentation of the assessment is all that is necessary; 2) “new controls should be considered,” in which a user needs to consider if the vulnerabilities are acceptable and, if not, determine where to apply food fraud mitigation resources to yield an acceptable level of vulnerabilities; and 3) “new controls are strongly suggested.”

--- PAGE BREAK ---

With regard to other anti-fraud activities at the USP, Moore said that the USP is developing a toolbox of methods for skim milk powder to deal with unknown adulterants, not known adulterants, and standardized and validated methods for unknown adulterants. The first tool is for detecting the non-protein nitrogen content of skim milk powder. More tools are being developed but are not yet ready for public comment, he said. They include such methods as non-targeted analysis with near-infrared or nuclear magnetic resonance and an amino acid fingerprinting method. The USP has also developed reference materials containing melamine in a skim milk powder matrix as standards for users to verify the performance of non-targeted methods and expects to release them later this year. In addition, the USP has several other ongoing projects related to EMA, such as adulteration of paprika oleoresin and olive oil.

Moore said that the USP is continuing to improve its Food Fraud Database. A compilation of scholarly and media reports on food ingredient fraud from 1980 to 2010, the database can be used to assess existing and emerging risks and trends for EMA. It also includes a library of detection methods reported in peer-reviewed journals. A large amount of new data is being vetted for validity and usefulness and will be entered into the database in early to mid 2015.

GFSI Adds Food Fraud to Guidance

The Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI), Paris, France (www.mygfsi.com), is a global consortium that brings together international food safety experts from the entire food supply chain to share knowledge and promote a harmonized approach to managing food safety across the industry. Karil Kochenderfer, GFSI’s North American representative, said that the GFSI doesn’t audit or certify companies for food safety but instead sets standards for food safety schemes that companies around the world can meet. It sets benchmarking schemes and identifies certifying bodies, auditors, and inspection teams that inspect facilities. This system ensures that companies adopting the standards have good food safety protocols in place. She added that the GFSI’s network of schemes for various sectors such as grain, meat, processing, retail, and others has been growing at a double-digit rate over the past ten years.

The GFSI issued a position paper on mitigating the public health risk of food fraud on July 14, 2014, outlining steps that food businesses should take to protect consumers from the consequences of food adulteration, counterfeiting, and other illegal practices. In its position paper, the GFSI proposed adding two key elements to its guidance document, available on the GFSI website. The first would require food companies to carry out a food fraud vulnerability assessment in which information is collected at the appropriate points along the supply chain (including raw materials, ingredients, products, and packaging) and evaluated to identify and prioritize significant vulnerabilities for food fraud. The second would require food companies to put in place appropriate control measures to reduce the risks from these vulnerabilities. These control measures would include a monitoring strategy, a testing strategy, origin verification, specification management, supplier audits, and anticounterfeit technologies. A clearly documented control plan would outline when, where, and how to mitigate fraudulent activities.

The GFSI issued a position paper on mitigating the public health risk of food fraud on July 14, 2014, outlining steps that food businesses should take to protect consumers from the consequences of food adulteration, counterfeiting, and other illegal practices. In its position paper, the GFSI proposed adding two key elements to its guidance document, available on the GFSI website. The first would require food companies to carry out a food fraud vulnerability assessment in which information is collected at the appropriate points along the supply chain (including raw materials, ingredients, products, and packaging) and evaluated to identify and prioritize significant vulnerabilities for food fraud. The second would require food companies to put in place appropriate control measures to reduce the risks from these vulnerabilities. These control measures would include a monitoring strategy, a testing strategy, origin verification, specification management, supplier audits, and anticounterfeit technologies. A clearly documented control plan would outline when, where, and how to mitigate fraudulent activities.

Elements of the food fraud guidance document were sent to technical experts in the food industry last year, Kochenderfer said, and the document is undergoing revision. The GFSI will incorporate the new elements, which address food safety rather than EMA, in the next full revision of its guidance document to be released in 2016.

The FDA Adds Focus on Adulteration

The Food Safety Modernization Act mandates that the FDA work to prevent both intentional and unintentional contamination of foods through a variety of preventive and risk-based strategies and through enhanced regulatory authority. It provides for increased food protection by requiring food companies to identify and implement preventive controls to ensure that adulterated products are not sold and to share their food safety plans with the FDA. The law requires the FDA to issue seven implementing regulations by May 31, 2016. The agency published its proposed rule “Focused Mitigation Strategies to Protect Food Against Intentional Adulteration” in the Federal Register on December 24, 2013, with a June 30, 2014, deadline for comments. The proposed rule focuses on protection of food against intentional adulteration caused by acts of terrorism, but it also included a request for public comment on whether it should address EMA and how.

According to Douglas Karas, FDA spokesperson, the agency is reviewing the comments received and will publish a final rule by the court-ordered deadline of May 31, 2016. The FDA intends to publish within six months after publication of the final rule a guidance document to help businesses identify actionable process steps and implement focused mitigation strategy requirements.

The FDA has created a software program called the Food Defense Plan Builder to help companies develop customized plans to minimize the risk of intentional adulteration, and on September 3, 2014, the agency posted training videos on how to use the program. Users answer a series of questions about the food facility and the food manufactured, processed, packed, or held there to develop a comprehensive food defense plan, including a vulnerability assessment, broad and focused mitigation strategies, and an action plan. The software and videos are available free of charge on the FDA’s website.

In October 2014 the FDA posted an online learning module consisting of three videos to help the seafood industry, retailers, and state regulators ensure that seafood products are properly labeled. The module, “Fish and Fishery Products Hazards and Controls Guidance—Learning Module Videos,” provides an overview of the federal identity labeling requirements for seafood offered in interstate commerce; a list of the specific laws, regulations, guidance documents, and other materials pertinent to the proper labeling of seafood; a description of the FDA’s role in ensuring the proper labeling of seafood; and tips for identifying mislabeled seafood in the wholesale distribution chain or at the point of retail. It also references the FDA’s DNA testing at the wholesale level to evaluate proper labeling of seafood species.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Leading Food Fraud Categories

The January 10, 2014, report “Food Fraud and ‘Economically Motivated Adulteration’ of Food and Food Ingredients” by Renée Johnson of the Congressional Research Service (www.loc.gov/crsinfo.gov) used data from the USP’s Food Fraud Database, the National Center for Food Protection and Defense’s EMA Incident Database, and other sources to identify leading food categories with reported cases of food fraud. They are as follows:

• Olive Oil. Olive oil is often substituted or diluted with lower-cost oils.

• Olive Oil. Olive oil is often substituted or diluted with lower-cost oils.

• Fish and Seafood. Some higher-value fish and seafood are replaced with less expensive fish.

• Fish and Seafood. Some higher-value fish and seafood are replaced with less expensive fish.

• Milk and Milk-Based Products. Milk from cows has been adulterated with milk from sheep, buffalo, and goat antelope and with reconstituted milk powder, urea, rennet, and other food and nonfood products.

• Honey, Maple Syrup, and Other Natural Sweeteners. Honey and maple syrup have been adulterated with other syrups and sugars. Honey has also contained unapproved antibiotics or other additives and heavy metals.

• Honey, Maple Syrup, and Other Natural Sweeteners. Honey and maple syrup have been adulterated with other syrups and sugars. Honey has also contained unapproved antibiotics or other additives and heavy metals.

• Fruit Juices. Some juices, especially expensive ones like pomegranate juice, have been diluted with water or a cheaper juice such as apple or grape.

• Coffee and Tea. Ground coffee might contain ground leaves and twigs as well as roasted corn, ground roasted barley, and roasted ground parchment. Instant coffee may include chicory, cereals, caramel, parchment, starch, malt, and figs. Tea may contain leaves from other plants, color additives, and colored sawdust.

• Coffee and Tea. Ground coffee might contain ground leaves and twigs as well as roasted corn, ground roasted barley, and roasted ground parchment. Instant coffee may include chicory, cereals, caramel, parchment, starch, malt, and figs. Tea may contain leaves from other plants, color additives, and colored sawdust.

• Spices. Saffron, the world’s most expensive spice, has been found to have added glycerin, sandalwood dust, tartrazine, barium sulfate, and borax. Ground black pepper has been shown to have added starch, papaya seeds, buckwheat, flour, twigs, and millet. Vanilla extract, turmeric, star anise, paprika and chili powder are also prone to fraud.

• Organic Foods and Products. Conventionally produced foods fraudulently labeled as organic have been detected by the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture for a range of foods and food ingredients from both domestic and international suppliers.

• Clouding Agents. Food-processing aids to enhance the appeal or utility of a food or food component are often used in fruit juices, jams, and other foods. Of particular concern is the fraudulent use of phthalates as a substitute for other ingredients.

Neil H. Mermelstein, IFT Fellow,

Neil H. Mermelstein, IFT Fellow,

Editor Emeritus of Food Technology

[email protected]