PACKAGING

How to Pick a Co-Packing Partner

A worker performs quality control inspection at a bottling operation. ©mladenbalinovac/Getty Images

For packaged foods manufacturers, co-packing operations are often synonymous with co-manufacturing or co-processing and involve processing as well as packaging. There are many reasons brands opt for co-packing instead of building their own manufacturing operations, and these include food safety and the need for financial and business agility. Criteria for co-packer selection include scale, price, building trust, and connecting on shared value.

Why Work With Co-Packers?

Here’s a breakout of three key reasons companies choose to work with co-packers.

• Food Safety Expertise. In addition to Good Manufacturing Practices, co-packers’ processes are certified and Global Food Safety Initiative compliant. To this end, food safety management systems such as Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points, Standard Operating Procedures, and Integrated Pest Management are used. Managing allergens and complying with labeling regulations also require adherence to specific guidelines.

“Verification is essential to ensure the co-packer maintains not only food safety but also quality standards,” says Jan Lillemo, principal consultant with Lillemo & Associates. He recommends obtaining food safety records and quality measurements, as well as records of product shipments for routine inspection. This ensures proper processing, handling, and packaging of the product.

• Finance Conservation. When company finances are not used for capital investment associated with factory building and equipment acquisition, they can be diverted to invest in distribution, marketing and sales, and infrastructure. Interest-ingly, to ensure that funds can be rapidly liquidated when startups fail, many investor funds cannot be used for capital equipment.

Because many entrepreneurs need to use co-packing operations, the processing and packaging industry has provided programs to assist with small production runs at co-packer facilities and brand building. Tetra Pak, for example, aids new brands by buying co-packing time to package the new brand on the co-packer’s process and packaging machinery. This allows access to the equipment until brand volumes are established, and a Tetra Pak machinery purchase is viable.

There are many reasons brands opt for co-packing instead of building their own manufacturing operations, and these include food safety and the need for financial and business agility.

Co-packing also decreases the financial drain by using economies of scale for more economical sourcing of packaging materials and formats. This is especially true if a co-packer focuses on a specific package format, such as aluminum cans with different labels applied for various brands.

Jason Robinson, business development director – food at the Agricultural Utilization Research Institute in Minnesota, a nonprofit corporation that fosters long-term economic benefit through value-added agriculture, expands: “For a brand just beginning to scale distribution, the value of a co-packer is often not just in the ability to produce more product in a short time frame, but also in decreasing the opportunity cost. An emerging start-up typically won’t have the financial wherewithal to hire a production supervisor, a quality control specialist, and a food scientist, as well as marketing, finance, and sales functions.”

Also, sales and production volume are interconnected. Robinson explains that by working with a co-packer, the entrepreneur can take off some of those hats to focus on growing sales. Minimum order quantities (MOQ) can be a substantial hurdle to overcome for an emerging business. If the product’s shelf life is exceeded before the co-packer MOQ product inventory is sold, the entrepreneur must weigh both the MOQ and potential financial cost of unsalables. Robinson also points out that the opportunity cost of not using a co-packer and managing production internally often results in an inability to focus on sales growth due to the demands of managing day-to-day production.

Co-packers can also play an important role for large food companies that may not be able to justify spending on new equipment or to divert production from equipment in order to produce new—and potentially less profitable—products. Thus, large food manufacturers often employ co-packers for new products or package changes due to the need for financial agility and to lower the capital risk of assessing new product and package ideas in the marketplace.

• Business Agility. Food manufacturers routinely guide the co-packers that handle their short-term increased production demands. However, many established brands also find co-packers helpful in managing operations if they have expertise in a new area of packaging or processing or within a new global market.

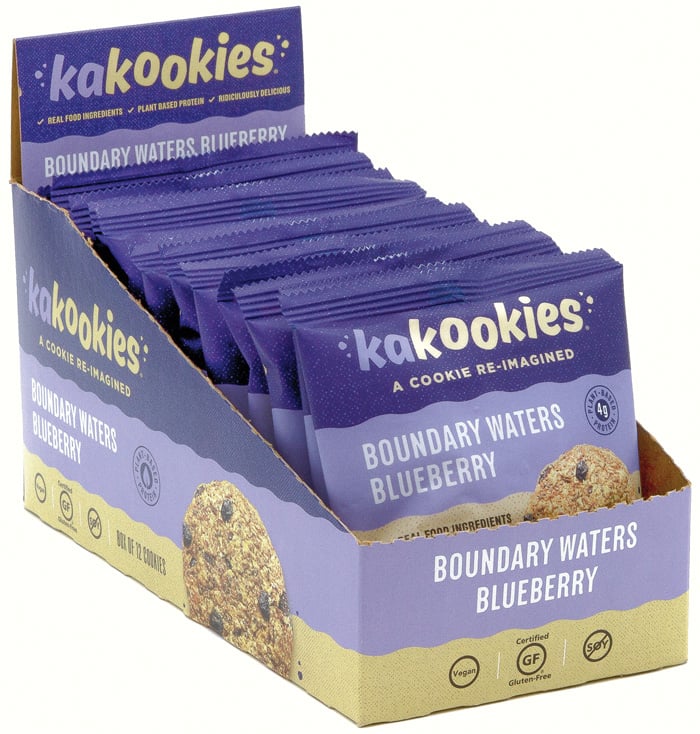

Kakookies uses a co-packer for its plant-based grab-n-go 12-count case pack of Boundary Waters Blueberry product. Photo Courtesy of Kakookies

For entrepreneurial brands where this knowledge base is lacking, a co-packer can replace the need to learn and then apply the intricacies of food manufacturing and packaging. For example, new product launches of packaged deli meat processed via high pressure processing (HPP) were initially achieved using a co-packer, often the HPP equipment manufacturer. In this case, vacuum packaging, seal integrity, and package barriers were critical parameters that were optimized by the co-packer. As manufacturing expertise matured, HPP units were installed and managed within the brand operations.

The same is true when an established brand converts from one packaging format to another. For example, the gum industry’s conversion from a focus on individually wrapped pieces of gum within a secondary package to rigid-lidded high-density polyethylene containers, blister packages, and dispensers was managed by using co-packers for the filling, handling, and sealing of these new package formats. Once the packaging acumen was refined, production lines were retooled to accommodate the new package format and were moved to the gum companies.

The Amazing Chickpea brand mixes are filled into stand-up pouches at one co-packer while spreads are filled into jars at another. Photo courtesy of The Amazing Chickpea

Sunil Kumar, owner of The Amazing Chickpea, a marketer of spreads, mixes, and powders, opted to use co-packers to keep his company focused on sales and growth. Because few co-packers are nut-free, gluten-free, dairy-free, and vegan, and able to work with both wet and dry processing and packaging, he chose to work with multiple co-packers. He has found that all have different ways of working: One may be open to procuring ingredients and another may ask to move the finished products within two weeks of production because of warehouse space constraints.

Integration with logistics, flexible machinery, robotics, mobile operations, and other means also achieves agile co-packaging manufacturing. New linkages between supply chain logistics and co-packing operations are designed to lower the overall cost of getting food to retailers and directly to consumers. According to the European Co-Packers Association, 83% of co-packers surveyed offer logistics services. Expandable and interchangeable packaging equipment maximizes production line flexibility, but efficiency is sacrificed. Readily adjustable robotic technology is advancing rapidly, eliminating the need for some frequent production line adjustments. For example, mobile beverage canners bring operations directly to many small-scale craft breweries.

Finding the Right Co-Packer

To select a co-packer, experts advise factoring in the following considerations.

• Define the Scale Needed. Volume flexibility is critical because a startup’s production volume may scale up rapidly. For most products, processing and packaging line speeds are difficult to increase with labor alone. Hence, equipment needs to run consistently at slow and high speeds, or the product needs to tolerate fast processing and packaging compatible with short production runs. For example, for horizontal and vertical form-fill-seal and rotary seal machines to achieve an adequate seal, jaw sealing temperatures need to be within a defined temperature range for a specific dwell time. Suppose the production line speed is decreased drastically to align with low production volumes. In that case, the longer seal dwell time may produce seals that are not easily opened by the target consumer or seals that do not seal well due to elastomer escaping the seal area. The correct scale of operations is essential to achieving optimal packaging.

• Pinpoint the Price Threshold. Price remains one of the main reasons that brands move from co-packing to establish independent operations. For co-packing, prices are often on a per-unit basis with minimum volume thresholds. The per-unit price can vary drastically based on quantities produced. This is primarily due to the conversion changeover, setup, clean-up times, and manufacturing labor. Some high-efficiency co-packers lower these conversion times and employ consistent base products and packaging, which is then fine-tuned with unique ingredients and labeling. This reduces costs yet yields a less unique product and package.

Due to the need to use consistent processing and packaging to optimize co-packing pricing, second phase manufacturing is a significant development area. Second phase manufacturing presents an opportunity for entrepreneurial brands to monetize many co-packers’ high efficiency with the need for brand personalization. There are many secondary packaging tools to attain a unique image for consumers when starting with a consistent primary package.

• Establish Trust. In co-packing, trust is needed in upper management and on the production floor. Trade secrets, patentable processes, and formulations, as well as other product and package parameters, are shared with co-packers at a high level of transparency; trust is essential. Trust between brands and co-packers means brand owners are confident the product is safe for consumers and that contractual arrangements between brands and co-packers are honored. This involves confidence in ingredient and packaging sourcing as well as safety and quality in manufacturing operations.

There are many measures and means by which to assess operations and then develop trust. For example, high management and employee turnover are used as an indicator that employees are not valued or that problems exist within the co-packer. Established co-packers have operational protocols that are shared with brands to convey the process by which they handle issues as they arise. These issues include food safety concerns, recalls, package sourcing, supply chain issues, ingredient changes, machinery maintenance, consumer complaints, and label changes.

Many operational protocols and communication pathways are derived and refined with joint co-packer–brand stress tests. For example, a food safety recall stress test involving a packaging-derived contaminant would assess co-packer response and resolution time and assess inherent ability to track and then eliminate food contamination via the packaging supplier processes and altered co-packer packaging intake cleaning processes. The stress test conveys a depth of knowledge of the internal company communication culture and value chain. After the stress test, adjustments are made to ensure that there are known and approved operational protocols.

• Connect on Shared Value. While trust is essential, alignment on shared value ensures that when issues arise, priorities are consistent with brand culture. This involves attaining a deep understanding of a company’s mission and culture. For an eco-friendly brand, for example, a co-packer with environmental values may align with brand values if the co-packer has optimized processes to decrease food and water waste during processing.

“Having an on-site QA team to ensure that data is collected to confirm that proper specifications are used during production is essential,” says Catalyst Creamery founder Katie Jones. “Even though the product will be run on dairy equipment, plant-based milk does not fit animal-based milk parameters or equipment settings. Further, I have had pipes blown and pumps clog during production trials when temperature conditions were not followed closely. I work with co-packers that understand that I am the expert in the functionality of working with plant-based milk.” Having a co-packer that acts as a co-partner in creating the company’s vegan cheeses eases communication that supports process improvements.

As with many entrepreneurs, engaging in the production process with a co-packer also adds value, Jones says. “Being on the production room floor is a highlight for me. I love getting a process dialed in and finding efficiencies, and I enjoy making my product as much as eating it.”

Authors

-

Claire Koelsch Sand Member

Claire Koelsch Sand, PhD, contributing editor to Food Technology and an IFT Fellow, is a global packaging leader with more than 35 years of food science and packaging experience. Sand is the owner and founder of Packaging Technology and Research, LLC, and an adjunct professor at Michigan State University and CalPoly.

Categories

-

Food Technology Magazine

-

Food Processing and Technologies

-

Packaging Equipment