Military and Humanitarian Rations

PROCESSING

On October 7, 2001, the United States military began bombing sites in Afghanistan in an attempt to secure air superiority over the Taliban government and allow further safe air strikes and deployment of ground troops.

The air strikes were followed by the dropping of leaflets informing the Afghan population that the war is against terrorist groups such as Osama bin Laden’s Al Qaeda organization and governments who support terrorist groups, and not the general population. Along with the leaflets, the U.S. began dropping about 37,000 individually wrapped food packages called “Humanitarian Daily Rations” (HDRs) in remote areas of Afghanistan to help feed refugees fleeing the bombing. When ground troops enter the area, as it is expected they will, they will be utilizing combat rations.

To find out more about the military rations and the humanitarian rations, I spoke with Jerry Darsch (phone 508-233-4402), Director of the U.S. Dept. of Defense (DoD)’s Combat Feeding Program in the Soldier Systems Center (formerly known as Natick Labs) in Natick, Mass.

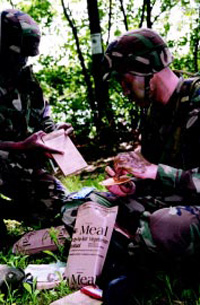

Military Rations

The basic combat ration is the Meal, Ready-to-Eat (MRE), a self-contained ration consisting of a full meal packed in a flexible meal bag that is lightweight and fits easily into the soldier’s rucksack and field uniform pockets. It is designed to sustain an individual engaged in heavy activity such as military training or during actual military operations when normal foodservice facilities are not available.

The MREs must meet rigorous standards, Darsch said. They must be shelf stable for a minimum of 3 years at 80°F and a minimum of 6 months at 100°F; be able to be dropped out of aircraft by parachute from 1,280 ft; be able to be thrown out of a helicopter without a parachute from 100 ft; withstand storage, distribution, and handling in environmental extremes from –60°F to +120°F; be resistant to wildlife in that area; taste good; and look good. “That’s a fairly substantial challenge,” he said.

The meal consists of 9–10 components—an entree, a starch product (rice or pasta), some candy, wet-pack fruit, a number of beverage bases (flavored drinks, coffee, cocoa, tea, cider, and soon even cappuccino), crackers, spreads, cakes, and an accessory packet containing a wet nap, chewing gum, and a small bottle of tabasco sauce. The entree is packaged in a retort pouch, and the other items, except the tabasco sauce, are packaged in flexible packaging. The various items are placed into the meal bag, a khaki-colored flexible package made of an extruded polypropylene blend designed to prevent chemical and biological contamination, and the bag is heat sealed.

The retort pouch used for the entrees used to be made of a trilaminate material but now has four layers—a polypropylene food-contact surface, aluminum foil, nylon, and polyester. The addition of nylon added no significant cost or weight and increases the performance capability on the battlefield, Darsch said. It makes the package a little tougher to survive rough handling, particularly in a cold-weather environment.

All components are placed into the menu bag and heat sealed. The bag takes 90 cu in of space and weighs approximately 1.5 lb. Each MRE provides about 1,300 kcal, and a day’s ration includes three MREs per soldier per day. There are 24 different menus. Four of the menus are vegetarian. Except for the beverages, the entire meal is ready to eat. The entree may be eaten cold or heated in a variety of ways, including submersion of the entree package in hot water or by use of a flameless ration heating device that has been included in each meal bag since 1993. The MRE has a substantially longer shelf life than 3 years at 80ºF if stored in a cool environment before distribution. A kosher and halal version is also available for those who maintain a strict religious diet. Each meal provides approximately 1,200 kcal and has a shelf life of 12 months.

The soldier’s basic unit load provides enough product for 3 days. If the soldier goes into combat, he can field-strip the MRE. The logistics system deploys with the soldiers, so they never run out of combat rations, Darsch said. The Defense Logistics Agency (the Defense Supply Center in Philadelphia) prides itself in getting the war fighters what they need and exactly where and when required.

A special-purpose ration that could be used by the Special Operations Forces (SOF) in Afghanistan is the Food Packet, Long Range Patrol (LRP), a lightweight, extended-shelf-life ration to be used during initial assault, special operations, and long-range reconnaissance missions. Each LRP weighs 1 lb, and each soldier carries one per day, compared to 3 MREs per day for regular soldiers. Considered a restricted-calorie, full-day ration for a maximum of 10 days, each menu provides 1,560 kcal. There are 12 menus consisting of dehydrated entrees, cereal bars, cookie and candy components, instant beverages, accessory packets containing coffee, sugar, cream, toilet paper, matches, and chewing gum, and plastic spoons. The ration has a shelf life of 10 years at 80ºF.

The intent, Darsch said, is to provide a very lightweight, restricted ration ideally suited to the kind of mission the SOF are called on for. Instead of the pillow pack used for the freeze-dried entree in the earlier LRP, the new version uses a brick pack, which reduces the space required by 33%, to lighten the load as much as possible and free up available space to make sure the soldier has mission-essential equipment along with rations.

He added that no matter how good they make the MRE, it’s always better if eaten hot. Historically, soldiers had to rely on trioxane fuel bars, which took time to heat the MRE. The soldier had to put the fuel bar on the ground, place the canteen cup and stand over the bar, add water, light the bar, and wait 30 min to heat the water enough to heat the food in the entree pouch. It required 10 oz of water and 30 minutes of valuable time, and the soldier had to be stationary while he did it. That’s not always a good thing in combat.

Now a flameless ration heater is included in each MRE menu bag. Natick, with the cooperation of industry, developed a flat, 22-g heating element in a long polymeric sleeve. The soldier has to rip the top off, open the chipboard carton, drop the pouch into the sleeve, and add 2 oz of water. An exothermic reaction raises the temperature of the entree by 100ºF in 10 min. The beauty of it, Darsch said, is that the soldier doesn’t have to be stationary. If he can’t eat during that 10 min, he can put the pouch back into the chipboard carton and into the pocket of his uniform. The sleeve will maintain the temperature for up to 1 hr.

Humanitarian Rations

Early on October 8, hours after the U.S. and allied forces bombed terrorist targets inside Afghanistan, the U.S. began its Enduring Freedom Humanitarian Relief Mission. Two U.S. Air Force C-17 transport jets airdropped about 37,000 humanitarian rations to concentrations of refugees inside Afghanistan. It marked the first U.S. military airdrop of humanitarian aid to the region and the first time this particular type of airdrop was used.

The HDRs were dropped from the airplanes via one-time-use, heavy-duty cardboard containers called Tri-Wall Air Delivery Systems (TRIADs). Each TRIAD contains 470–490 HDRs. As the planes approach the drop zone, they are depressurized and the cargo doors are opened, then the pilots pull the aircraft nose up about seven degrees, causing the containers to roll out of the aircraft. The containers are tied to a static line, or harness, that tightens and flips them over once they are clear of the aircraft, releasing the prepackaged rations, which “float” down. The empty cardboard container is then released, and the harness retracted. This method eliminates the need to drop pallets of food via parachute, permits wide distribution of the rations, and prevents palletized loads from falling into enemy hands.

The HDR weighs 38 oz and comes in a bright yellow pouch wrapped in double-thick plastic, strong enough to withstand extreme environmental conditions and high-altitude drops. The label reads “This is a food gift from the people of the United States of America” in English, Spanish, and French. A graphic shows a male silhouette with a spoon to his mouth.

Developed by DoD in 1993 as a civilian alternative to the MRE, the HDR is designed to provide a full day’s nutritional requirement for one moderately malnourished individual. The 2,200-kcal ration is easier for a nutritionally depleted system to absorb than the 4,400-kcal MRE. To provide the widest possible acceptance by consumers with diverse religious and dietary restrictions around the world, the HDR contains no animal products or animal by-products, except minimal amounts of dairy products, and no alcohol or alcohol-based ingredients.

It contains two vegetarian entrees based heavily on lentils, beans, and/or rice, as well as complementary food items such as bread, a fruit bar, a fortified biscuit, peanut butter, and spices. A spoon and a nonalcohol-based moist towelette are the only nonfood components in the meal bag. The entire meal is ready to eat. The entrees may be eaten cold or heated by placing the entree package in hot water or heating the contents in a pot over a flame. The HDR has a shelf life of 18 months at 80ºF.

Improving Rations

Darsch said that there is no comparison between what was put into the package for the soldier of today and what was in the MRE during Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm in the Persian Gulf War of 1991. Those operations used a combat ration designed in 1985–88 that was acceptable to the war fighter at that time. However, the expectations of the war fighter had changed dramatically by 1990–91. Under a vigorous combat ration improvement program begun in 1991, the philosophy shifted from a “father-knows-best” approach to a system in which the items that go into the ration are warrior selected, warrior tested, and warrior approved.

Now, the product developers go to the field much more frequently than in the past and spend a great deal of time with the soldiers under realistic field conditions—in rain, sleet, snow, and mud—and do a lot of interviews. They find out what the soldiers want added to the MRE, develop prototype menus, then go back and test the prototype menus under realistic field conditions. Natick started the improvement program in 1991, and the first major changes were made in 1993. Every year, 2–3 menus are changed, Darsch said.

“We are now able to get into the procurement system new components and new menus within 18 months of identifying the change,” he said. “That has a great deal to do with having a very strong and robust partnership with each Service, the Defense Supply Center, our vendors, the veterinary folks, and the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture.”

As result of this aggressive combat feeding program, they have increased the number of menus in the MRE from 12 to 24 and eliminated such former unpopular items as omelet with ham, tuna with noodles, and potatoes au gratin, and added such new items as Jamaican pork chop with noodles, beef teriyaki, seafood jambalaya, pot roast with vegetables, beefsteak with mashed potatoes, and black bean and rice burrito. There is a lot of variety, Darsch said. A complete listing of the menus can be found at www.dscp.dla.mil/subs/rations/meals/mres.htm.

In addition to developing complete menus, Natick is involved in developing specific foods. For example, during the Gulf War, Hershey Foods developed with Natick a heat-stable chocolate bar. The traditional Hershey bar was reformulated to provide a high-heat–stable chocolate during Operation Desert Shield (“melts in your mouth, not in the sand”). It worked beautifully at high heat conditions, Darsch said, but, unfortunately, it couldn’t survive the temperature cycling that MREs are exposed to. For example, sometimes MREs are stored in a refrigerated environment of 60–80°F, then offloaded into 8-ft x 8-ft x 20-ft ISO container, where the internal temperature might spike to 120°F, then moved into a cooler at 80–90°F. The product couldn’t withstand that cycling—it bloomed so much that it turned into powder—and was discontinued in 1994.

Natick has since developed the Hooah Bar, a performance-enhancing ration component that Darsch calls “an energy bar with a purpose.” It was developed basically from the ground up, he said, with extensive literature reviews and “the best food science and technology minds in the country.” Natick has trademarked the name and label and licensed it to a company in the U.S. for commercial sales. Natick has also developed a drink called Ergo (for “energy-rich, glucose-optimized”), also with rigorous development and testing among Rangers. It provides a 10% increase in physical performance vs control.

Developing New Processes

The Combat Rations Network for Technology Implementation (CORANET) is a DoD Manufacturing Technology Program sponsored by the Defense Logistics Agency. Its objective is to develop and adapt modern manufacturing processes for the U.S. industrial base, to ensure the timely availability of affordable, high-quality, and varied combat rations to the military. All current producers of MREs and HDRs participate in the network.

The foods in the MREs and the HDRs rely, for the most part, on thermal processing, but Natick is involved in three new food science programs with industry and academia to investigate other processes that may be of benefit to the military and the public by producing foods with better color, odor, appearance, and nutrient retention. The programs are part of the Dual Use Science and Technology (DUST) program, managed by the Natick Soldier Systems Center under the direction of C. Patrick Dunne (phone 508-233-5514), Senior Advisor to DoD’s Combat Feeding Program. DUST is a consortium of industrial and academic partners whose goal is to evaluate the use of emerging technologies to develop improved products for the military and the public. Natick awards contracts, and the partners design the equipment and produce prototype products for Natick and the industrial partners to evaluate. Natick has awarded contracts for three projects: a 3-year project on pulsed electric field (PEF) processing at Ohio State University, begun in 1999; a 3-year project on high-pressure processing (HPP) at Flow International Corp., begun last year; and a 2-year project on microwave sterilization at Washington State University, begun this year.

According to Dunne, the goal is primarily to lay the groundwork for putting improved processes into place in industry for making better food for military purposes and the commercial market. Basically, government is investing in some technologies that they want to use to improve DoD’s capability to fight wars, he said, because food is a key component of keeping soldiers’ performance at the highest level. The government doesn’t want to fit the bill alone, but wants to attract new industrial firms who may not have been government contractors before, to build up the industrial base to be able to meet a big surge in military demand for food.

The MREs have been provided primarily by smaller firms, but the DUST program is now attracting some major producers. Industrial partners include Kraft, Tetra Pak, General Mills, Hirzel, Ameriqual, American Electric Power, and Diversified Technologies for the PEF project; Flow International, the National Center for Food Safety and Technology, Kraft, Hormel, ConAgra, Procter & Gamble, and SOPACKO for the HPP project; and Kraft, Hormel, Truitt Bros., Inc., Rexam Containers, Graphics Packaging Co., and the Ferrite Co. for the microwave project.

PRODUCTS & LITERATURE

Pulsed-Light Sterilization of meat, fish, and vegetables is being studied by researcher A. Demirci at Pennsylvania State University, using the SteriPulse system manufactured by Xenon Corp. The mercury-free pulsed light system’s ultrahigh peak power provides narrow pulses only a few hundred millionths of a second in duration that are 80,000 times brighter than sunlight and powerful enough to kill all microorganisms. For more information, contact A. Demirci at [email protected] or Xenon Corp., 20 Commerce Way, Woburn, MA 01801-9711 (phone 800-936-6695, fax 781-938-3594, www.xenoncorp.com) —or circle 315.

Food Spoilage Monitor charts the timeline of a product’s temperature life and records changes with the range of –40ºC to +85ºC (–40ºF to +185ºF). The Heatwatch™ TR-1 system monitors food product temperatures, shelf life, and spoilage for such temperature-sensitive food items as fresh fruits and vegetables, frozen foods, dairy, meat, seafood, and wine. The system consists of intelligent sensors and a software package for programming and data retrieval. Each sensor chip can download a report on four different functions of a specific mission (product life cycle). The results may be entered for up to 40 different time/temperature points. The unit is normally attached to the outside of shipping or storage containers with a self-adhesive label. The sensor/recorder module may also be deposited within or mixed with container contents. For more information, contact Shockwatch®, 7979 Brookriver Dr., Suite 200, Dallas, TX 75247 (phone 800-527-9497, fax 214-638-4512, www.shockwatch.com) —or circle 316.

by NEIL H. MERMELSTEIN

Editor