Improving the Gut Feeling

NUTRACEUTICALS & FUNCTIONAL FOODS

Although not widely discussed in public, gastrointestinal (GI) disorders are quite common in the United States. According to the American College of Gastroenterology, Arlington, Va., more than 95 million Americans experience some kind of digestive problem, such as an upset stomach, indigestion, heartburn, or even an ulcer. More than 10 million people are hospitalized each year for care of GI problems, and the total health care costs exceed $40 billion annually. GI disorders range from minor ailments such as diarrhea, constipation, and irritable bowel syndrome to more serious illnesses that require hospitalization or medication, such as ulcers and colon cancer.

Consumers in the United Kingdom and Japan appear to be more aware of the importance of a healthy GI tract, which consists of the muscular tube from the mouth to the anus. This past September, the Digestive Disorders Foundation and Japanese-based probiotic drink manufacturer Yakult sponsored Gut Week 2002 in the UK (www.gutweek.org.uk). The goal of Gut Week was to increase public awareness of digestive health. The main message for the public was to look after their digestive system by eating a healthy diet and not ignoring symptoms, no matter how embarrassing.

Home remedies for conditions such as constipation, diarrhea, and indigestion include prunes and senna pods, according to information from Gut Week. Another remedy sent to Gut Week sponsors was dandelion leaves boiled with a lump of coal for a severe case of constipation.

“Some folklore remedies certainly have a sound medical/scientific basis,” said Martin Sarner, secretary of the Digestive Disorders Foundation. “For example, prunes and senna contain chemicals that have a laxative effect and are used in a number of medical preparations. Dandelions may contain a diuretic, but dehydration wouldn’t help constipation. As for the coal, I think it would cause more trouble than it would cure!”

Other nutrients have more scientific backing for maintaining a healthy GI tract. A recent article in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (Duggan et al., 2002) listed vitamin A, zinc, glutamine, arginine, probiotics, and prebiotics as potential protective nutrients for the GI tract. This month’s article will focus on the beneficial effects of probiotics and prebiotics.

Probiotics

Probiotics are live microbial food ingredients that have a beneficial effect on human health. In addition to the GI tract, studies also link probiotics to benefits regarding the immune system, allergies, and viral infections.

“The probiotic bacteria most commonly studied include members of the genera Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium,” said Mary Ellen Sanders, Research Professor at Dairy Products Technology Center, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, Calif., in IFT’s Scientific Status Summary on Probiotics (Sanders, 1999). They function by adhering to the intestinal lining and preventing harmful bacteria from growing.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Some of the specific mechanisms by which probiotics exclude undesirable organisms are thought to include the following: production of inhibitory substances, blocking of adhesion sites, competition for nutrients, degradation of toxin receptors, and stimulation of immunity (Chow, 2002).

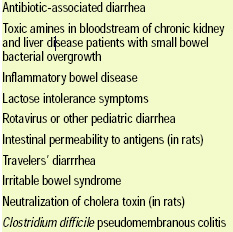

“Probiotic bacteria have been shown to improve the clinical outcome in many intestinal disease targets,” said Sanders (see Table 1). “Although the clinical protocols frequently fall short of the double-blinded, placebo-controlled ideal, the scientific evidence suggests that probiotic bacteria, consumed at high levels (109–1011/day), can decrease the incidence, duration, and severity of some intestinal illnesses.”

“Probiotic bacteria have been shown to improve the clinical outcome in many intestinal disease targets,” said Sanders (see Table 1). “Although the clinical protocols frequently fall short of the double-blinded, placebo-controlled ideal, the scientific evidence suggests that probiotic bacteria, consumed at high levels (109–1011/day), can decrease the incidence, duration, and severity of some intestinal illnesses.”

Studies indicate that some probiotic bacteria or their end products may inhibit Helicobacter pylori infection, which is associated with chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, and risk for gastric cancer.

Probiotics are most commonly found in yogurt and other fermented dairy products. Stonyfield Farm, Londonderry, N.H., for example, currently uses six probiotics in its yogurt products: Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus reuteri, and bifidobacteria.

“These are the probiotics that have been widely researched and published in terms of cultured milk products,” said Kasi Reddy, Vice President of Research and Development and Quality Assurance for Stonyfield Farm. “Our interest in using these probiotics stems from widely published animal and human studies with positive effects in diversified areas of gastrointestinal health and immune system support. Stonyfield Farm also uses L. reuteri, a unique probiotic culture with more than 120 scientific papers supporting it as being a superior probiotic,” said Reddy.

Stonyfield Farm has exclusive rights to L. reuteri and currently uses it in all of the company’s yogurts, yogurt drinks, and cultured soy products. Studies indicate that it inhibits the growth and activity of Salmonella, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus, Listeria, and the yeast Candida. It has also been shown to support the immune system and to have therapeutic and prophylactic effects against both viral and bacterial diarrhea, thus enhancing the body’s resistance to GI disease.

Although yogurt is the most common vehicle for probiotics, work presented at this year’s IFT Annual Meeting & Food Expo® indicated that there are other potential vehicles:

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Fruit Pieces. Maguiña et al. (2002) used a vacuum impregnation process to create probiotic-containing apple pieces. They detailed how they incorporated Bifidobacterium species into the porous spaces of Granny Smith apples at levels higher than 107 cells/g. The apples appeared to be a good vehicle for bifidobacteria, as shown by sensory evaluation and viability of the culture at 4°C, at levels higher than 106 cells/g.

• Fermented Whey. Garcia et al. (2002) discussed how they created a whey-based fermented product containing in excess of 106 cfu/mL of L. reuteri and Bifidobacterium bifidum. The product fermented for approximately 11 hr and was prepared with 2% L. reuteri and 0.5% B. bifidum. They found that the fermented whey was stable during 30 days of refrigerated storage and had good sensory scores.

• Fermented Milk. Huerta-Espinosa et al. (2002) discussed their work to obtain a probiotic fermented milk using a strain of L. casei spp. rhamnosus. The culture was a mix of L. casei, L. bulgaricus, and S. thermophilus. The best results were obtained when the milk was inoculated at 7%. The time found for coagulation was 5 hr at 37°C. The product had a cream color and pleasant aroma and was accepted by 80% of the consumer panel.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are nondigestible food ingredients that beneficially affect the host by selectively stimulating the growth and activity of one species or a limited number of species of bacteria in the colon. Oligosaccharides in human breast milk are an example because they facilitate the preferential growth of bifidobacteria and lactobacilli in the colon of exclusively breast-fed neonates (Duggan et al., 2002).

“Prebiotics, by definition, must have dietary fiber properties, but dietary fibers may not be prebiotic, as prebiotic infers selectivity and bacteria modification to a more healthy condition,” explained Bryan Tungland, Vice President of Scientific and Regulatory Affairs at U.S. inulin supplier Imperial Sensus, Sugar Land, Tex. “Based on the body of scientific evidence, prebiotics include such dietary compounds as lactulose, lactitol, the fructooligosaccharides, alactooligosaccharides, and inulin,” he said. “However, several compounds also have shown the ability to stimulate bifidobacteria and potentially to have specific effects on gut microflora composition and could with time and more research be classified as prebiotic. These include tagatose, arabinogalactan, galactosyllactose, and possibly theanderose.”

Prebiotics function by acting as selective food for bacteria, such as bifidobacteria and lactobacilli, that have been shown to provide certain health-promoting functions. They use the prebiotics for food to grow in numbers and produce by-products such as the short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and other metabolites of the fermentation/utilization process, explained Tungland. These SCFAs help protect intestinal wall health and stimulate repair, if needed.

The health-promoting bacteria create an environment that is inhospitable for “bad” bacteria to reproduce in. A small “bad” bacteria population means that fewer intestinal proteins are consumed (probiotics are saccharolytic) and fewer harmful protein-based by-products are released. These by-products of proteolytic bacteria—ammonia, phenolic products, amines, and N-nitroso compounds—have been linked to various cancers and ulcerative colitis (Birkett et al., 1996; Buddington et al., 1996). Animal studies and in-vitro testing have further suggested a role of various prebiotic fibers in intestinal immune function (Pierre et al., 1997; Lim et al., 1997; Kelly-Quagliana et al., 1998; Field et al., 1999; Meyer et al., 2000).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

SCFAs produced by prebiotic fermentation, particularly butyrate, play a key role in colon health, said Tungland. They are thought to stimulate cell division and apoptosis, the colon’s mechanism to remove excess or redundant cells (Wason and Goodland, 1996). Unlike the small intestine, which derives energy from various bodily sources, the colon epithelial cells derive energy solely from SCFAs. As a preferred nutrient, butyrate indirectly prevents colonic mucosal reduction, which develops within days of oral starvation.

Another GI health disorder, intestinal permeability or “leaky gut syndrome,” is an indicator for potential disease. As gut barrier function is lost, chronic bowel inflammation—caused by mucosa’s exposure to foreign bodies—may appear, explained Tungland. To keep the colonocytes healthy and minimize inflammation, it is important to maintain a positive balance between crypt cell growth and luminal cell loss by apoptosis or sloughing (Lynn et al., 1994). While different fiber types have different effects on epithelial cell growth, it is generally accepted that prebiotic fibers have greater influence on cell growth, via SCFA production, than other fibers such as cellulose.

Research will continue to investigate prebiotic effects on overall GI health, specific effects on certain pathogenic species (Clostridium difficile, E. coli, Listeria, and others), and potential influence on certain chronic diseases, such as diverticular disease, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and certain cancers, said Tungland. Additional research will look at factors to enhance immunity and improve calcium absorption, which may help improve bone health in developing individuals and minimize effects of bone loss.

Prebiotics, such as inulin, can be used in almost all food categories and help, in a systems approach with other functional ingredients, to make foods that are fat and/or sugar free or have reduced caloric content and have the eating quality of their full-calorie counterparts, said Tungland. “Because of their ease of use and incorporation into foods, prebiotics are showing up in many foods, such as beverages, bars, cereals, wellness breads, yogurts, frozen desserts, confections, fermented and fluid “healthy milk” products, extruded snacks, and baked goods.

Stonyfield Farm uses inulin in most of its products. One example is its Drinkable yogurt. “By adding prebiotics such as inulin, we are continuing the Stonyfield tradition of offering healthy all-natural and organic products with additional healthy components,” said Reddy.

Inulin is a unique prebiotic because it has been researched clinically for more than a century and has a substantial body of scientific evidence to support its unique prebiotic role, said Tungland. Also, based on its chemical makeup and functional properties, it is quite unique in its effects on texture modification. Inulin has relatively low viscosity and is easily incorporated into foods. It helps to reduce fat and/or sugar content and improve the overall texture, mouthfeel, and flavor of foods while providing a selective prebiotic fiber source for the health-promoting bacteria.

“The specific health benefit for inulin that we found interesting in collaborative research with Orafti Active Food Ingredients, Malvern, Pa., was its effect on increasing calcium absorption, along with bifidogenic benefits,” said Reddy. “We have the highest available milk calcium in our products. Inulin helps boost calcium absorption.”

The potential for both probiotics and prebiotics as nutraceutical ingredients is great. As the research behind these continues, look for more health benefits to arise.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Potential Pros for Probiotics

Most of the research supporting the health benefits of probiotics focuses on the gastrointestinal system and the immune system. Here are other conditions that probiotics may help to alleviate:

• Allergies. Babies that are fed probiotics while they are being weaned may be less likely to develop the allergy-related skin condition eczema. Researchers in the Dept. of Biochemistry and Food Chemistry at the University of Turku in Finland studied 21 infants who showed evidence of atopic eczema and were at heightened risk for chronic allergic disease. Supplementation of a hydrolyzed whey formula with Bifidobacterium lactis significantly reduced the numbers of Escherichia coli and prevented an increase in the numbers of bacteroides during weaning. The authors concluded that bifidobacterial supplementation appeared to modify the gut microflora in a manner that may alleviate allergic inflammation (Kirjavainen et al., 2002).

• Viral Infections. A study on the prevention of GI infections suggested that probiotics may also be effective against viral infections. In this study, children were randomized to receive either Lactobacillus GG or a placebo after hospital admission. Because many infections are acquired in the hospital, the researchers decided to test the protective effects of probiotics in this setting.

Of the 81 children in the study, 15 (18.5%) experienced diarrhea during their hospitalization. Stool analysis revealed that rotavirus was the most common cause. Probiotic supplement use was associated with a significantly reduced risk of diarrhea; only 3 children (6.7%) in the group given probiotics had diarrhea, compared to 12 children (33.3%) in the placebo group (Szajewska et al., 2001).

Be a part of the 2003 Nutraceutical & Functional Food Buyer’s Guide

The first annual Nutraceutical & Functional Food Buyer’s Guide will be published in the December 2002 issue of Food Technology. This comprehensive guide will include nutraceuticals such as amino acids, botanicals, enzymes, vitamins, minerals, fruits and vegetables, proteins, soy, dietary fiber, probiotics and nutritional fats and oils. It will also be available online at www.ift.org. Don’t miss your opportunity to be listed in this timely buyer’s guide!

To obtain a Listing Application, contact Denise Bayers at 1-800-IFT-FOOD (438-3663).

Advertisers in the December issue are entitled to a 50-word company description in addition to the company name listing.

AD SPACE DEADLINE: November 4 AD MATERIALS DEADLINE: November 8

by LINDA MILO OHR

Contrtibuting Editor

Chicago, Ill.

References

Birkett, A., Muir, J., Phillips, J., Jones, G., and O’Dea, K. 1996. Resistant starch lowers fecal concentrations of ammonia and phenols in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 63: 766-772.

Buddington, R.K., Williams, C.H., Chen, S.C., and Witherly, S.A. 1996. Dietary supplement of neosugar alters the fecal flora and decreases activities of some reductive enzymes in human subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 63: 709-716.

Chow, J. 2002. Probiotics and prebiotics: A brief overview. J. Renal Nutr. 12(2): 76-86.

Duggan, C., Gannon, J., and Walker, A.W. 2002. Protective nutrients and functional foods for the gastrointestinal tract. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 75: 789-808.

Field, C.J., McBurney, M.I., Massimino, S., Hayek, M.G., and Sunvold, G.D. 1999. The fermentable fiber content of the diet alters the function and composition of canine gut associated lymphoid tissue. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 72: 325-341.

Garcia, H.S., Hernandez, A., Robles, V., Angulo, J.O., and De la Cruz-Medina, J. 2002. Preparation of a whey-based probiotic product with Lactobacillus reuteri and Bifidobacterium bifidum. Paper 15A-11 presented at Ann. Mtg., Inst. of Food Technologists, Anaheim, Calif., June 16-19.

Huerta-Espinosa, V.M., Urrutia, E., Casariego, A., and Hernandez, A. 2002. Use of probiotic bacteria to obtain fermented milk. Paper 15A-14 presented at Ann. Mtg., Inst. of Food Technologists, Anaheim, Calif., June 16-19.

Kelly-Quagliana, K.A., Buddington, R.K., Van Loo, J., and Nelson, P.D. 1998. Immunomodulation by oligofructose and inulin. In Proc. Of Nutritional and Health Benefits of Inulin and Oligofructose, p. 53. Natl. Insts. of Health, Bethesda, Md.

Kirjavainen, P.V, Arvola, T., Salminen, S.J., and Isolauri, E. 2002. Aberrant composition of gut microbiota of allergic infants: A target of bifidobacterial therapy at weaning. Gut 51(1): 51-55.

Lim, B.O., Yamada, K., Nonaka, M., Kuramoto, Y., Hung, P., and Sugano, M. 1997. Dietary fibers modulate indices of intestinal immune function in rats. J. Nutr. 127: 663-667.

Lynn, M.E., Mathers, J.C., and Parker, D.S. 1994. Increasing luminal viscosity stimulates crypt cell proliferation throughout the gut. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 53: 227A.

Maguiña, G., Briceño, G.A., Tapia, M.S., Rodríguez, C., Roa, V., and Welti-Chanes, J. 2002. Incoporation of Bifidobacterium spp by hydrodynamic mechanism in a porous fruit matrix. Paper 15E-25 presented at Ann. Mtg., Inst. of Food Technologists, Anaheim, Calif., June 16-19.

Meyer, P.D., Tungland, B.C., Causey, J.L., and Slavin, J.L. 2000. The immune effects of inulin in vitro and in vivo. Agro-Food-Industry Hi-Tech, Nov./Dec., pp. 18-20.

Pierre, F., Perrin, R., Champ, M., Bornet, F., Meflah, K., and Menanteau, J. 1997. Short-chain fructooliogsaccharides reduce the occurrence of colon tumors and develop gutassociated lymphoid tissue in Min mice. Cancer Res. 57: 225-228.

Sanders, M.E. 1999. Probiotics. Food Technol. 53 (11): 67-77.

Szajewska, H., Kotowska, M., Mrukowicz, J.Z., Armanska, M., and Mikolajczyk, W. 2001. Efficacy of Lactobacillus GG in prevention of nosocomial diarrhea in infants. J. Pediatr. 138: 361-5.

Wason, H.S. and Goodland, R.A. 1996. Fibre-supplementated foods may damage your health. Lancet 348: 319-320.