Thinking Big About Obesity

Four experts share their ideas for tackling this mounting public health problem with approaches that range from food formulation to food psychology.

The scope of the global obesity epidemic is vast, and the statistics are sobering. In 2014 nearly 2 billion people around the globe were overweight or obese, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The prevalence of obesity worldwide has doubled since 1980, and most of the world’s population lives in countries where overweight and obesity kill more people than underweight, WHO points out. In the United States, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data, more than two-thirds of the population is overweight or obese. The CDC estimates the medical cost of obesity in the United States at $147 billion annually.

So it’s hardly surprising that just about everyone—from television personalities to public health professionals—seems to have an opinion on the subject. In this special report, Food Technology cuts through the clutter of the commentary on obesity to present insights from four experts whose thoughts on the topic are thought provoking, well substantiated, and sometimes surprising.

One thing upon which all agree is this: the tools for fighting obesity must include more than the oft-repeated counsel to “eat less and exercise more.” That’s sound advice, of course, but to deal effectively with the worldwide obesity crisis, new strategies and tactics are required. And that’s what the experts interviewed on the pages that follow have to offer.

• European researcher Julian Mercer is involved in several projects that explore the body’s complex mechanisms for hunger and satiety. His research interests include investigating ways to modify fiber so that it can be used in foods that help to keep hunger pangs in check.

• Brian Wansink of the Food and Brand Lab at Cornell University has spent decades studying eating behavior and food psychology. Some of his latest research offers a powerful motivation for clearing kitchen counters of food—unless it’s fruit.

• For veteran food industry executive Hank Cardello, a personal health crisis prompted a decision to focus on improving the food system. He maintains that food companies need to think more creatively about crafting lower-calorie, better-for-you foods.

• Nutrition professor Barry Popkin advocates a public policy–focused approach to fighting obesity that includes taxes on fattening fare and front-of-package labeling programs that are simple for shoppers to understand.

The interviews featured in this issue come from IFT’s FutureFood2050.com website, an initiative launched as part of IFT’s 75th anniversary celebration with the goal of exploring innovative approaches to sustainably feeding the world’s rapidly growing population, which will total more than 9 billion by 2050.

The interviews featured in this issue come from IFT’s FutureFood2050.com website, an initiative launched as part of IFT’s 75th anniversary celebration with the goal of exploring innovative approaches to sustainably feeding the world’s rapidly growing population, which will total more than 9 billion by 2050.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Going With the Gut—and the Brain—in Order to Satisfy Hunger

By David Derbyshire

Imagine tucking into a small bowl of breakfast cereal and feeling full until lunch, then eating a light sandwich that keeps the hunger pangs at bay until supper time. It may sound like the ultimate fantasy for dieters, but a team of food scientists believes the creation of new filling foods like these could help reduce growing obesity rates.

Fat-fighting tactics that work from the inside out by appeasing appetites could be the wave of the future, says Julian Mercer, a leading UK obesity researcher and head of the European Full4Health project, a European Union–funded program exploring the body’s mechanisms of hunger and satiety to help combat obesity.

Fat-fighting tactics that work from the inside out by appeasing appetites could be the wave of the future, says Julian Mercer, a leading UK obesity researcher and head of the European Full4Health project, a European Union–funded program exploring the body’s mechanisms of hunger and satiety to help combat obesity.

“Obviously we could just have a mantra of ‘eat less and exercise more,’ but it’s quite difficult for people to regulate that just through a conscious process,” says Mercer. “What we are actually doing in several different projects is trying to look at how hunger and satiety are regulated, and whether there are ways we can support people to consume a little bit less food.”

The Food-Gut-Brain Axis

Based at the Rowett Institute of Nutrition and Health at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, Mercer and the Full4Health team are probing the food-gut-brain axis—the body’s internal signaling mechanism that helps determine whether we feel full, hungry, or just plain gluttonous.

These sensations are complex and linked only partly to the physical sensation of food in our stomachs. The presence of food in the gut also triggers the release of an array of hormones, most of which signal to the brain when it’s time to stop eating, what types of food are being consumed, and how they should be processed in the gut. One gut hormone is the odd man out, signaling hunger to the brain.

“Combined, this information contributes to decision making on how much you eat in terms of calories and what sorts of foods you might look out for over the next period of time,” says Mercer, who came into food research through the back door 25 years ago as an endocrinologist. “What we are looking at is how this food-gut-brain axis functions, and how manipulating the diet influences its function.”

In addition to getting gut signals, the brain is constantly receiving information about how much fat our bodies are storing from a hormone called leptin. This information helps us maintain a relatively constant body weight in the long term. If levels of leptin fall, due to dieting or starving, the brain responds by increasing appetite—one reason it is so difficult for overweight people to fight the flab.

Our brains also respond to food—particularly sugary and fatty food—with the release of “reward” and “pleasure” neurotransmitters. The surge in these chemicals can override our feelings of fullness, allowing us to indulge in sweet, fatty desserts despite already being full from dinner.

Protein Power

Full4Health, which was launched in February 2011 with $11.3 million of funding, is focusing on animal research into the biological mechanisms that underpin satiety and hunger. The project is also looking at how the psychological and physiological reaction to food changes as we age by analyzing the brain response to food in children, adolescents, the middle-aged, and elderly using functional magnetic resonance imaging scanning.

While the human studies are ongoing, the animal research has already identified new roles and functions for gut hormones. The work is also adding weight to the “protein leverage hypothesis,” says Mercer—the idea that eating behavior is driven by the need to consume protein. Evidence for this idea has come from a Full4Health team led by Margriet Westerterp-Plantenga at Maastricht University in the Netherlands. Researchers there found that volunteers consuming a high-protein diet ate less than those on normal or low-protein diets but did not report feeling hungrier, although the reasons for this effect are still unclear.

Armed with the research results, Mercer’s team helped the UK retail chain Marks & Spencer develop a brand of high-protein ready meals called Simply Fuller Longer, launched in 2010. The foods typically contain 10 grams of protein per 100 grams, about 5 grams more than comparable ready meals. In a study of the diet at Rowett, volunteers who ate the Simply Fuller Longer meals for four weeks saw an average weight loss of 5%, and researchers found that the high-protein meals delayed the onset of hunger by one to two hours.

Manipulating Fiber for Fullness

Manipulating Fiber for Fullness

Mercer is also a partner in Satiety Innovation (SATIN), a European project concentrating on manipulating fiber to make it even more filling. Fiber stays in the stomach longer than other foods do, increasing the feeling of satiety compared with other foods. And as fiber goes down the gut, it is fermented by gut bacteria that release short-chain fatty acids, which are also satiating.

The SATIN team is looking at fermenting or heat treating fiber to see if the natural properties of fiber from fruit, vegetables, and grains can be enhanced and then used as food additives, says Mercer. Jason Halford, who heads the SATIN collaboration of academics and industry at Liverpool University in England, demonstrated in August 2014 that consuming such a modified fiber—a proprietary whole grain flour treated with a heat-moisture process—can increase the length of time a person feels full. When volunteers had a 20-gram breakfast serving of the product in a smoothie, they consumed 5% less food at lunch and dinner. SATIN research is also looking into the effects of arabinoxylan and beta-glucan, soluble fibers found in grains.

“An obvious fiber you eat in the morning is breakfast cereal, and that’s a place you could directly incorporate [enhanced fiber], but you could potentially incorporate it into bread and other normal things you eat,” says Mercer. “Ready [to eat] meals would be another obvious choice.”

Less Is More

Research on filling foods is unlikely to move beyond protein and fiber, says Mercer, because other micronutients such as fats have far less potential. But one new line of satiety research that he believes has promise involves mimicking the effects of weight-loss surgery. Tests on rats by Full4Health researchers at Norwegian University of Science and Technology have shown that injecting the anti-wrinkle treatment Botox into the vagus nerve in the stomach leads to weight loss. The jab paralyzes the nerve, which plays a key role in feelings of hunger and controls the passing of food through the intestines.

Mercer says it’s too soon to predict how important the satiety approach to weight loss could become, “since we are still at the proof-of-concept stage in terms of whether satiating foods can deliver long-term health benefit,” he says. He adds that “it is unlikely that [the effect] would be big enough to help individuals who already have a significant weight problem, but more realistic to think that the approach might be helpful for people who want to maintain their body weight within the normal/overweight range and counter progression towards a more problematic weight.”

And he stresses that any kind of food product designed for greater satiety will also need to be palatable to consumers. “It has got to be something that is recognizable and something that tastes okay,” he says. “Ultimately you can easily invent diets that will help people maintain their weight, but if [the diets] are unpalatable they will be a failure.”

David Derbyshire is a freelance environment and science writer based in Winchester, United Kingdom.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Designing an Environmental Approach to Weight Loss

By Kirsten Weir

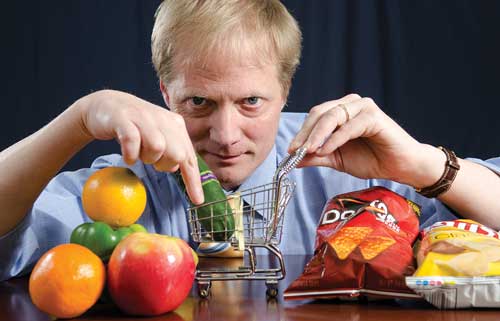

Feel like you’re constantly fighting temptations to eat too much of the wrong kinds of foods? It’s not you—it’s the environment around you, says Brian Wansink, director of the Food and Brand Lab at Cornell University and author, most recently, of Slim by Design: Mindless Eating Solutions for Everyday Life (HarperCollins, 2014).

Wansink, who has researched eating behavior, food psychology, and food marketing for more than two decades, contends that the current environment is stacked firmly against healthy eating habits no matter how much willpower you have. But he argues the environmental cues that encourage overconsumption can be easily modified so that consumers will reach for the healthier foods, in the right portions.

Wansink, who has researched eating behavior, food psychology, and food marketing for more than two decades, contends that the current environment is stacked firmly against healthy eating habits no matter how much willpower you have. But he argues the environmental cues that encourage overconsumption can be easily modified so that consumers will reach for the healthier foods, in the right portions.

Wansink’s findings have influenced menu design in chain restaurants and contributed to the introduction of 100-calorie snack packages that help control portion size. And from 2007 to 2009 he served as executive director of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture’s (USDA) Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, the agency charged with developing dietary guidelines and promoting the USDA food guidance system (MyPlate, MyPyramid, Food Guide Pyramid). His website, slimbydesign.org, offers scorecards to help consumers customize their eating environments.

We asked Wansink how to create a healthy food environment, why the food industry should get on board, and what he predicts for the future of our waistlines.

Question: You’ve done hundreds of studies on eating behavior and uncovered fascinating factors that influence us to overeat. What’s surprised you most?

Wansink: What consistently surprises me is that regardless of what it is that influences somebody—whether it be the size of a plate, the lighting, the order of things on a menu, what the person next to you is doing—almost all people will say, “Okay, yeah. Maybe that influences other people, but it doesn’t influence me. I’m immune to those things.”

Most people are unwilling to acknowledge these influences in the first place. So why would they change? That’s what makes it so important to set up our environment so we can make the right choices without having to think about it—without having to have willpower.

Question: How, for example, can we stage our environments for success?

Wansink: There are five major environments to focus on: our home, the two or three restaurants we go to most often, our main grocery store, where we work, and where our kids go to school. There are things you can do in all those areas to eat a little bit better and eat a little bit less. You want to tilt your eating life in the direction it’s going to work most for you rather than against you.

Let’s take home, for example. We went into 240 homes in Syracuse [N.Y.] and photographed and measured the entire kitchen, and weighed the people in the home. We found that if a home has a bag of potato chips visible in the kitchen, on average, that person’s going to weigh 9 pounds more than the neighbor who doesn’t have potato chips out. If there’s a box of breakfast cereal sitting out, that person is going to weigh 21 pounds more than the neighbor. But if they have even one piece of fruit visible anywhere in the kitchen, on average they’re going to weigh 8 pounds less. Simply decluttering your counters of food—unless it’s fruit—is going to be the first step in the right direction.

Let’s take home, for example. We went into 240 homes in Syracuse [N.Y.] and photographed and measured the entire kitchen, and weighed the people in the home. We found that if a home has a bag of potato chips visible in the kitchen, on average, that person’s going to weigh 9 pounds more than the neighbor who doesn’t have potato chips out. If there’s a box of breakfast cereal sitting out, that person is going to weigh 21 pounds more than the neighbor. But if they have even one piece of fruit visible anywhere in the kitchen, on average they’re going to weigh 8 pounds less. Simply decluttering your counters of food—unless it’s fruit—is going to be the first step in the right direction.

In schools, we [Cornell Center for Behavioral Economics in Child Nutrition Programs] started the Smarter Lunchrooms Movement to get kids to eat better. We’re in over 20,000 schools nationwide. A lot of efforts have put healthy food in lunchrooms, but they haven’t been very successful in actually getting kids to eat it. So the Smarter Lunchrooms Movement was set up to guide kids to pick up the apple instead of the cookie—all the while thinking it was their own volition that was leading them to do so.

We recently launched an app that allows principals or even students to visually go through a lunchroom. If fruit is in a nice bowl in a well-lit part of the line, they get a point. If it’s in two or more places, they get a second point. If milk is in the front of the beverage cooler, they get a point. If at least a third of all the milk being sold is white milk, they get another point. The app adds up your score [to determine] whether the lunchroom is making you slim by design or heavy by design.

Question: Are you optimistic that making such changes will help turn around the obesity epidemic?

Wansink: I think obesity is going to be a lesser problem for most people [in the future]. The motto that people have been using to fight obesity up until now is “Willpower, willpower, willpower!” Trying to take food away from people, taxing it or legislating it, aren’t solutions that seem to be tenable. I think there’s going to be more of a focus on this notion of slim by design, where you’ve got sort of a win-win solution—solutions that are going to make companies more money, but also make people eat less.

When we first introduced 100-calorie packs, no company believed they could make money doing it. They said, “Sell less food? We’ll lose money!” But the opposite was true. We’ve found restaurants can charge for a half-sized portion up to 70% of what they charge for a full-sized portion, and it doesn’t decrease people’s likelihood of buying it. And if restaurants offer half-sized portions, people who don’t want to eat out because of the massive portion sizes might eat out a little more often. It broadens the market.

Question: What will the food industry look like in 2050?

Wansink: Food scientists over the years have spent most of their energy on issues of food safety and cost. And they’ve been unbelievably successful. In 1960, food comprised about 26% of the family budget. Now it’s about 7%. Food science has to be one of the most successful professions in the last 60 years! Where I see a huge gain is if they start turning their direction toward making food nutrient-advanced, lower-calorie, and even more satisfying.

There are a number of things that can be done to make a person believe they’re more sated. We find that if something takes longer to chew, for instance, people believe they’re more sated. Technology [can be used to] affect things from a sensory standpoint.

I think we’ll also see point-of-purchase meal development in the future. I think you’ll be able to go to a section of the supermarket where you can choose the meat you want, choose your vegetable, your sides. Then the meals will be flash-frozen to go. There will be a manufactured tray that enables you to heat it up so that everything is cooked to the right temperature. Maybe there’s a type of membrane over the food, or the compartments might have heat-resistant elements in the bottom, so that the apple-sauce is still cool, the meat is really hot, and the vegetables aren’t overcooked.

Question: How will food marketing and advertising change?

Wansink: I don’t think there will be major changes, but I think we’ll see marketing to children being turned over for the better. We did a study where we put Elmo stickers on wrapped cookies and on apples and bags of carrots. If you put the stickers on a cookie, it doesn’t do anything [to affect the number of cookies purchased]. People will buy those anyway. But if you put Elmo stickers on carrots or apples, it almost triples how many kids select carrots and apples. What benefits most from branding is the healthy products.

Kirsten Weir is a freelance science writer based in Minneapolis.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

From Industry Insider to Agent for Change

By Marc Gunther

Future consumers should be able to have their cake and eat it too—without getting fat.

So says Hank Cardello, who directs the Obesity Solutions Initiative at the Hudson Institute and wrote the best-selling book Stuffed: An Insider’s Look at Who’s (Really) Making America Fat and How the Food Industry Can Fix It (HarperCollins, 2009). Products like soft drinks, burgers, fries, pizza, and cupcakes should all be reconfigured as lower in calories and “better for you” to help alleviate the ongoing obesity crisis in America and other developed nations, argues this noted consultant to food industry powerhouses. Cardello contends this will enable the industry to grow even as the waistlines of consumers shrink.

So says Hank Cardello, who directs the Obesity Solutions Initiative at the Hudson Institute and wrote the best-selling book Stuffed: An Insider’s Look at Who’s (Really) Making America Fat and How the Food Industry Can Fix It (HarperCollins, 2009). Products like soft drinks, burgers, fries, pizza, and cupcakes should all be reconfigured as lower in calories and “better for you” to help alleviate the ongoing obesity crisis in America and other developed nations, argues this noted consultant to food industry powerhouses. Cardello contends this will enable the industry to grow even as the waistlines of consumers shrink.

Healthy junk food, Cardello maintains, need not be an oxymoron. “If we are going to make progress, we are going to have to focus on taking the most popular foods and modifying them,” he says. “That should be a rallying call for food scientists, kind of like putting a man on the moon. We’ve got to take french fries and burgers and everything else and … find ways to make them better for you without compromising them. This way, you don’t ask the consumers to change their eating habits.”

In fact, companies are already moving in this direction, Cardello explains. McDonald’s hamburgers are, as it happens, leaner than those of competing chains, and Chick-fil-A has reduced the amount of chicken in its sandwiches—saving the company money and reducing calories for the consumer.

A Man on a Mission

Cardello, who is 63, has spent more than 35 years working in and around the food industry. After earning an MBA from The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, he spent the early part of his career as an executive at General Mills, Anheuser-Busch, Coca-Cola, RJR Nabisco, and Sunkist Soft Drinks, where he was president. He then turned his attention to functional foods by working as a consultant and an executive for startups that sold ingredients including omega-3 fatty acids, a food additive made from calf’s milk aimed at enhancing the immune system, and a cooking oil without trans fats or cholesterol.

A midlife health crisis in the late 1980s helped turn Cardello from an industry insider into a consultant, entrepreneur, and author determined to use his influence to improve the food system. “I just crashed. I was burning the candle at both ends. I thought I had the flu. They gave me antibiotics. Nothing worked,” Cardello recalls. He decided that after he got better, he would “commit myself to helping people to live longer and healthier lives.”

The consulting firm that he launched in 1987, Chapel Hill, N.C.–based 27 Degrees North, advises the food industry on ways to address the obesity crisis. For example, he’s currently working with the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation, a coalition of food brands and retailers that collaborates with nonprofit groups including the Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, and Parent Teacher Association to reduce childhood obesity. The foundation’s industry members say that since 2009 they have collectively removed 6.4 trillion calories from the marketplace, which represents a 78 calorie reduction per person, per day. Meantime, its Together Counts educational campaign, which promotes family meals and exercise, has reached about half of the elementary school students in the United States.

“It’s very challenging to show cause and effect, but we are seeing a plateauing of obesity rates—and we are actually seeing some declines for kids,” Cardello says.

Good Food Is Good Business

Cardello says he would like to end the polarization that has long characterized the obesity debate. Often, public health advocates blame big food companies for selling food with too much fat, sugar, and salt, says Cardello. Put on the defensive, business executives note that they offer healthy choices and say consumers need to take responsibility for their own well-being. And politicians swoop in with proposals to tax junk food and ban super-size sodas. “They operate with a limited toolkit. The toolkit says tax, ban, constrain, regulate. Period,” he says. “It’s parental and futile.”

Despite the progress cited by Cardello—obesity rates have held steady lately and they appear to have declined for some children—more than one-third (or 78.6 million) of adult Americans and 17 percent (or 12.5 million) American children are obese, according to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Because getting people to change their eating habits is hard, and because research suggests that most diets don’t work, Cardello says it’s up to the food industry to find ways to make foods more nutritious and reduce the number of calories sold overall.

In fact, there’s evidence that such a strategy is even good business. In a series of industry-funded studies conducted by the Hudson Institute, Cardello has found that “consumer products companies with a higher proportion of their sales in lower-calorie, better-for-you foods demonstrate superior sales growth, operating margins, operating profit groups, and reputation.” The most recent study, published in 2014, analyzed the sales of 16 major food and beverage companies that are part of the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation and found that lower-calorie products drove virtually all of their growth, accounting for 52.5% of sales and 99% of growth over a five-year period ending Dec. 31, 2012.

The Coca-Cola Co., Atlanta, Ga., for example, has found that customers are drinking less soda and turning to beverages perceived as healthier—Dasani and Vitaminwater bottled water, Powerade sports drinks, Minute Maid juices, and Honest Tea, all owned by Coca-Cola. The company says it offers 180 low- and no-calorie beverages in the United States and Canada, representing nearly one-third of its beverage volume in North America.

“I wouldn’t have believed that when I was in the industry,” says Cardello, who used to market Diet Coke.

Investing in the Future

Investing in the Future

Still, there are limits to what the companies can do. In 2012 and 2013, Campbell Soup, Camden, N.J., acquired Bolthouse Farms, the baby-carrot company that markets healthy snacks for kids made out of fruits and vegetables, and Plum Organics, a health-oriented baby food company. Both are growing nicely, the company says. But when Campbell took sodium out of its iconic chicken noodle soup, sales declined.

That’s why Cardello says consumer products firms need to beef up their efforts to develop and market lower-calorie, better-for-you alternatives to popular foods, “as opposed to trying to come out with twigs and berries.” One big opportunity, he says, is for the industry “to really drill down on what makes the most popular foods more filling. . . . Satiety is a big buzzword.” Research shows that low-calorie density, high-volume foods like oatmeal, for example, leave people who eat them feeling fuller. “Maybe you then don’t have that mid-morning snack,” he says.

More work needs to be done on reducing portion sizes too, Cardello contends, citing such successful examples as 100-calorie snack packs of Oreo cookies, 90-calorie cans of Coke, and Mars’ pledge to limit candy bars to 250 calories.

Ultimately, says Cardello, he and the groups he advises like to find the common ground where the industry and anti-obesity activists can agree. “What’s important to me is that we get support from both sides of the aisle,” he says, because that’s the key to making faster progress.

Marc Gunther, who is based in Bethesda, Md., writes and speaks about business and sustainability.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Fighting Obesity on a Grand Scale

By Jennifer Weeks

Health advocates cheered in November 2014 when Berkeley, Calif., adopted a 1-cent-per-ounce tax on sugar-sweetened drinks. It was the first soda tax enacted in the United States after more than 30 failed attempts by other states and cities. But Barry Popkin, a leading expert on nutrition and obesity, saw it coming.

A distinguished professor of nutrition at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Popkin has been tracking the impact of new taxes on sweetened drinks and junk food in Mexico that started in 2014. Measures like these, he argues, are essential steps to address a global health crisis. For nearly a decade Popkin has warned that there are more overweight people than hungry people around the world. He cites two major reasons: reduced physical activity rates and aggressive worldwide marketing of cheap, processed foods with low nutritional value.

A distinguished professor of nutrition at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Popkin has been tracking the impact of new taxes on sweetened drinks and junk food in Mexico that started in 2014. Measures like these, he argues, are essential steps to address a global health crisis. For nearly a decade Popkin has warned that there are more overweight people than hungry people around the world. He cites two major reasons: reduced physical activity rates and aggressive worldwide marketing of cheap, processed foods with low nutritional value.

“The modern food system has reached every corner of the world,” says Popkin, who directs the University of North Carolina’s (UNC) interdisciplinary program on obesity and has studied nutrition trends over time in countries including Russia, Brazil, China, Mexico, and the Philippines. “So have modern technologies that reduce our energy expenditures. And the shift [in eating habits and physical activity patterns] is accelerating. A transition that took several hundred years for the United States happened in China in 15 years, and it’s happening in other countries equally rapidly.”

Dissecting Modern Diets

Popkin developed the concept of the “Nutrition Transition” to explain how eating habits and activity patterns shift as societies develop. In pre-industrial societies, people typically eat diets high in carbohydrates and fiber and low in fat and do most of their work by hand. Malnutrition is common, obesity rare. As societies mechanize and develop, food supplies increase and the need for labor decreases. People consume more fruits, vegetables, and animal protein, and nutritional levels improve. In high-income societies, people become sedentary and eat diets high in fat, sugar, and refined carbohydrates. Obesity increases, along with related health problems such as strokes and heart disease.

In Popkin’s view, modern packaged foods high in trans fats, saturated fats, sodium, and added sugars are taking over diets. “People all over the world increasingly are shopping at large supermarkets that feature products like sodas and sweetened juices, ready-to-eat cereals, and savory snacks,” he says. “And the marketing and retail sectors are creating new behaviors. Snacking was almost nonexistent before World War II. Today Americans consume about 22% of our calories from snacks. It’s the same in Mexico and Brazil, and China will be there in 15 to 20 years.”

But individual food products are only part of a broader problem, says Popkin. In a 2013 study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Popkin and his colleagues analyzed the diets of more than 4,400 American children between 2007 and 2010. They found that obesity was more closely correlated with eating what they called a typical Western diet—high in sugar-sweetened drinks, salty snacks, candy, french fries, and high-fat sandwiches—than with fast-food consumption. These results suggest that public health initiatives focusing on fast-food restaurants may have limited impact, he says, and that more priority should be placed on the balance of children’s diets.

“We need to find a way to move people away from very refined carbohydrate diets, and toward whole grains and fruits and vegetables and healthy unsaturated fats,” says Popkin. “It’s up to retailers and food manufacturers to start pushing and promoting healthier-for-you products. They are doing it now for upper-income families in the United States and the United Kingdom, because those consumers are demanding changes, but it also needs to happen in the lower- and middle-income world.”

“We need to find a way to move people away from very refined carbohydrate diets, and toward whole grains and fruits and vegetables and healthy unsaturated fats,” says Popkin. “It’s up to retailers and food manufacturers to start pushing and promoting healthier-for-you products. They are doing it now for upper-income families in the United States and the United Kingdom, because those consumers are demanding changes, but it also needs to happen in the lower- and middle-income world.”

Government Initiatives

Popkin says he would also like to see wealthy nations tax sweetened beverages and sugary desserts and require simple labels that help consumers judge the nutritional content of food. “We need to change the relative prices of highly processed, less healthy foods with some marketing controls and some government-sponsored front-of-the-package profiling,” he says.

Latin American countries are already leading on these issues, contends Popkin. In addition to Mexico’s new tax policies, Chile adopted a new food labeling system in 2014 that requires manufacturers to identify products high in sugar, fat, salt, or calories and bans advertising unhealthy products to children. Ecuador mandates labels on packaged foods that use a traffic light system to show whether products contain high (red), medium (yellow), or low (green) levels of fat, sugar, and salt. And Peru, Uruguay, and Costa Rica have ended the sale of “junk foods” in public schools.

In the United States, surveys during the past decade show that obesity rates have either declined or leveled off for low-income preschool children while remaining steady for older children and adults. In another recent study, Popkin and other UNC researchers analyzed possible explanations for this modest progress and whether it is likely to last. Combining household purchase data with nutrition surveys, they concluded that media coverage and public health campaigns focusing on obesity and the role of sugar-sweetened beverages may have been factors. Changes in the federal Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program, which provides supplemental foods to improve nutrition for low-income women, infants, and young children, may also have contributed.

“WIC is a success story. It is a health-focused program and has been modified in recent years to make the foods that it provides more healthy and nutrient-dense,” Popkin says.

But even though U.S. children consume about 35 fewer kilocalories per day now than they did a decade ago, according to Popkin’s calculations, that decline is only one-third of the reduction needed to meet the federal government’s goals for reducing child obesity. Moreover, the study authors noted, U.S. children and adults still eat too many excess fats and added sugars.

Food Politics

Congress and federal agencies are considering measures that could move Americans toward more healthy diets. But in Popkin’s view, health advocates are fighting an uphill battle against corporate and agricultural interests that dominate U.S. food policy.

One flash point is the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act, enacted in 2010, which revised school nutrition guidelines to reduce sodium levels and increase consumption of whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. The law, which is up for reauthorization in 2015, has drawn broad criticism from food manufacturers and some school districts whose officials say the standards are restrictive and expensive.

On another front, the Food and Drug Administration has proposed updates to the Nutrition Facts label carried on most packaged foods in the United States. The changes include information showing, for example, how many calories people consume if they eat an entire pint of ice cream or drink a 20-ounce bottle of soda in one sitting. They also would provide information about added sugars in foods.

Popkin believes, however, that the federal government should require front-of-the-package labeling that provides objective health rankings—an approach recommended by the Institute of Medicine in 2011. The institute offered several examples of labels that rated foods’ total nutrition with a system of stars or checks, based on nutrition point scores.

“Putting information about healthier and less healthy choices on packages is a way to move less literate consumers toward better options,” Popkin says. “That approach would make a difference, but the FDA wasn’t willing to pursue it.”

Jennifer Weeks is a Massachusetts freelance journalist who specializes in environment, science, and health.