Candid Career Conversations

Every life story has its unique plot twists, and no two career journeys follow the same path. But when IFT set out to study the career trajectories and workplace priorities of science of food professionals, some common themes emerged:

- Most food scientists love what they do, and they stick with what they love—eight out of 10 survey respondents have been employed in a food-related role throughout their career.

- Within the profession, career paths are often fluid. Nearly half said they had transferred their skills from one sector to another, especially those working in nonprofit organizations, government, and academia.

- Management support is the top contributor to job satisfaction, followed closely by work/life balance.

- Many women, gay, and Black survey participants say they’ve bumped up against barriers to advancement in the profession.

- Four out of 10 survey respondents report having a secondary source of paid income.

Fielded this past March and April, the Career Path Survey was the second in a two-part IFT career research initiative, with the first survey focused on compensation and benefits. Food Technology editors also spoke with some of the Career Path Survey respondents who indicated that they were willing to continue the conversation in a personal interview.

"And then the pandemic hit and caused me, along with many other folks, to kind of rethink their career paths."

What Matters Most

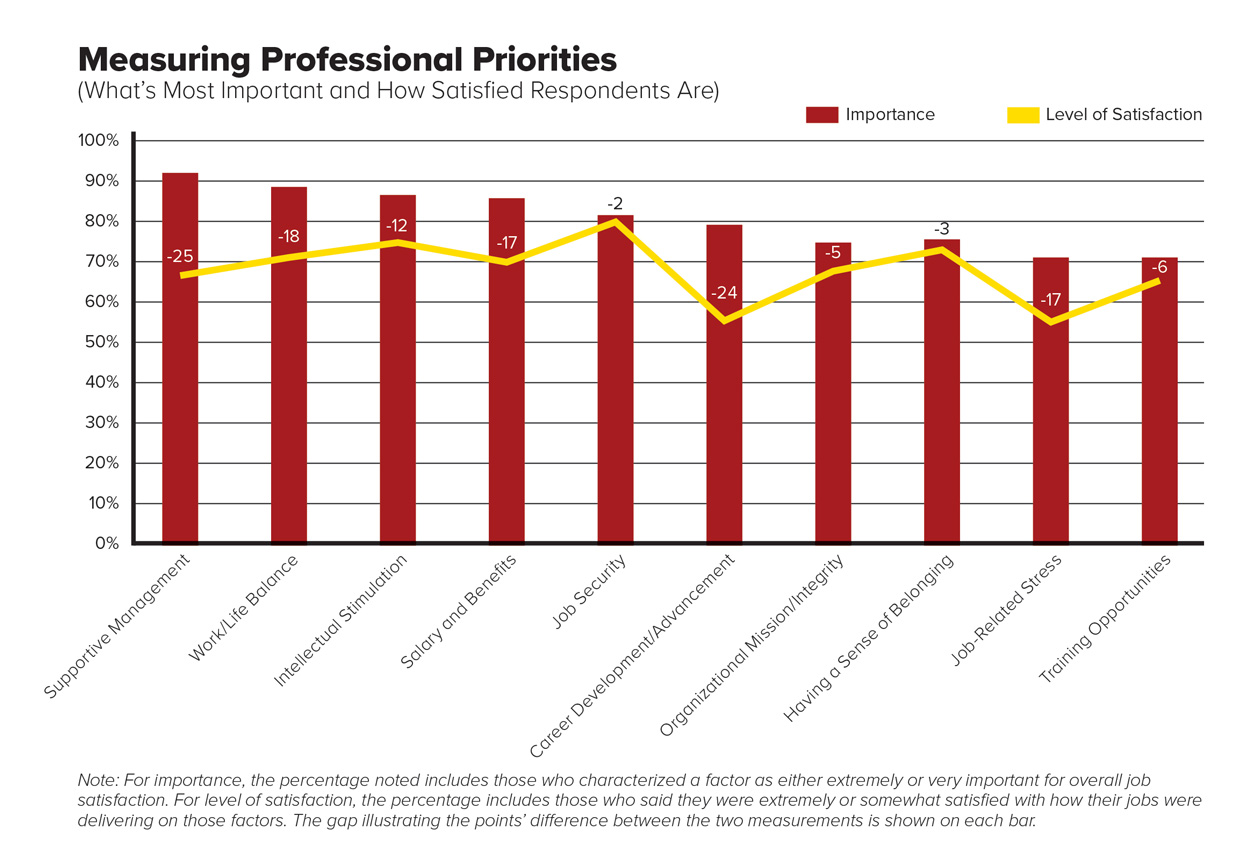

It’s no surprise that most science of food professionals enjoy their work; that’s been a recurring theme in IFT’s long history of salary survey research. But in the Career Path Survey, IFT’s research team dug a little deeper and came at the topic of job satisfaction in two different ways, asking survey participants what factors they considered most important and then exploring how satisfied they were with those aspects of their job.

Having supportive management led the list in terms of importance, with 92% rating it as either extremely important or very important. Work/life balance was a close second, cited as extremely or very important by 89%.

What survey respondents prioritized isn’t always matched by their real-world job experiences. Just 67% were extremely or somewhat satisfied with the quality of their management support, and 71% categorized work/life balance in that way.

The biggest gaps between importance and satisfaction were for supportive management and career development/advancement; the smallest gaps were for job security and having a sense of belonging.

One female research chef in her early 60s spoke anonymously about her disappointing experiences with senior management after her company was acquired by a larger organization. Post-acquisition, she says, she was stripped of a title she’d held for two decades and lost her support staff—all without much in the way of explanation.

When the chef told her manager, a vice president, that she thought the failure to inform her in advance about organizational changes was unprofessional, his response was a textbook example of a non-supportive, non-transparent management style. “Technically, I don’t have to explain anything to you,” he said, according to the chef.

Now the chef is considering exit strategies even though—with retirement on the horizon—she hadn’t anticipated making such a big change at this point in her career.

Victoria Wilson, who has worked in regulatory and scientific affairs for Nestlé Canada for almost seven years, happily reports a very different experience. She describes an open, collegial environment that encourages professional growth—and that’s earned the organization her loyalty.

“I report to a director, and my boss reports directly to the BEO (business executive officer),” says Wilson. “And she [the BEO] is very open. When I first joined the business, I had a one-on-one with her [so she could] get to know me on a personal level. … So they [top management] know you by your first name. It’s not like you’re just a statistic, not like you’re just a number.”

Measuring Professional Priorities (What’s Most Important and How Satisfied Respondents Are).

Note: For importance, the percentage noted includes those who characterized a factor as either extremely or very important for overall job satisfaction. For level of satisfaction, the percentage includes those who said they were extremely or somewhat satisfied with how their jobs were delivering on those factors. The gap illustrating the points’ difference between the two measurements is shown on each bar.

Relationships with managers are a critical element of employee retention, says Joy Lynn Hyer, senior compensation/survey analyst for HR Source, a nonprofit provider of human resources’ services.

“When employees trust leaders and are not micromanaged, they feel empowered to do their best work and go above and beyond to make the organization successful,” says Hyer. “They are also more likely to stay at an organization. When trust is lacking, employees are more likely to look elsewhere for a more supportive environment.”

Balancing Act

The challenge of achieving work/life balance is another often-repeated theme. It’s about boundaries, contends Patrice Lyon, a regulatory specialist for Ferrara Candy Company. Lyon works as a contractor for Ferrara, an arrangement she likes because it helps ensure that her work experiences are both varied and flexible.

In a role at a different company, Lyon says, her employer inundated her with calls while she was on a trip to visit family members that she hadn’t seen for more than a year because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Because of that experience, she now makes it a point to discuss vacation practices and policies before taking on a new project. “If I take a vacation, I want it to be a real vacation,” Lyon emphasizes. “I do not want to be checking my email or having my phone on just in case somebody ends up calling me.”

The importance of work/life balance should not be underestimated, research studies show. ADP Research Institute, for example, found that more than half of the 32,000 workers it polled in a 2022 study said they would take a pay cut in pursuit of better work/life balance. COVID triggered a change in employees’ expectations, ADP’s research underscores. “The pandemic signaled a paradigm shift as today’s workers reevaluate the presence of work in their lives,” said Nela Richardson, ADP chief economist, in a statement made at the time the research was announced. Employees’ view of work changed, Richardson observed, noting that many are “now prioritizing a wider and deeper range of factors that are more personal in nature.”

Intellectual stimulation was third on the Career Path Survey employment priority list, cited as extremely/very important by 87%, with 75% of respondents feeling extremely or somewhat satisfied with that aspect of their work lives.

For Matthew Moore, an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, having the freedom to pursue the kinds of research topics that he feels passionate about is among the main reasons that he loves academic life.

Moore finds meaning, not just in his own research exploration, but also in the experience of mentoring students. “The students in my lab are really, really good, and getting to see them develop … is a really fun and rewarding part of the job,” he says.

Work/life boundaries aren’t much of an issue for Moore. “I constantly think about my research, but it’s not like, ‘Oh, I have to work and put this time in.’ It’s more my lifestyle choice. It’s that I actually like doing the research, so it just kind of blurs the line.”

"I really like it because they know you, and it’s not superficial."

Professional Passages

Eighty-two percent of Career Path Survey respondents have worked in food-related roles for their entire careers. Just over half (54%) have been employed in the same sector within the food profession throughout their career, but that varies considerably from sector to sector.

Those working for a nonprofit group or nongovernmental organization had the most fluid careers, the survey showed. Just 14% reported working only in that field, while 57% have previously been employed in industry, 35% in academia, and 14% have been self-employed or worked as a consultant.

That contrasts with industry professionals, 67% of whom have worked solely in industry. Among those who reported employment in other sectors, 21% have been in academia, 7% were self-employed or consultants, and another 7% worked in government or nonprofits.

Among survey respondents employed in academia, just 40% have spent their entire careers in that setting. Forty-two percent previously worked in industry, 14% in government, 7% were self-employed/consultants, and 6% worked for a nonprofit group.

Fear of the unknown can be a barrier to career transitions, says Vay Cao, who has a PhD in neuroscience and developed a career transition platform called Free the PhD to help researchers find new careers.

“If you find yourself dreading or avoiding your day-to-day responsibilities wherever you are, you owe it to yourself to take a moment, step back, and evaluate if this is really the right fit for you,” says Cao. “I’ll say from personal experience that if you decide you need a change, the subsequent possibility for improvements in quality of life, work/life balance, financial stability, and so on can make all the stresses of transitioning well worth the effort.”

Moore says his career path moved him away from industry; his decision to build an academic career was crystallized by an internship experience. “You didn’t have as much intellectual freedom to explore the actual, fundamental purpose of something,” in that setting [industry], he reflects. “You actually had to focus specifically on, ‘Here’s our product. Let’s just optimize it so that people will buy it and that there’s a profit in it,’” he continues. “I think it was just that aspect I didn’t really like.”

Nutrition scientist Lisa Sanders, however, had the opposite experience. As she was completing a postdoctoral project with an eye toward pursuing an academic career, an opportunity in industry attracted her attention. “It [the opportunity] was with a food and ingredient company that was making a new dietary fiber, and they needed someone to help them with the research,” says Sanders. “It was a good opportunity because the postdoc was wrapping up, so I decided to go into industry, which was not what I had originally planned. But it turned out to be a perfect fit for me—even more so than the academic side, I realized very quickly.

“I just enjoyed the faster pace,” she continues. “I enjoyed the people that I worked with. Everybody was there to get their job done and do it well. And I just really liked working in that environment.”

"During my career, I followed the mantra: work hard, contribute, make a difference, and the pay will follow."

Scott Riefler, chief science officer at Sōrse Technology, an emulsion supplier for cannabis products, has transferred his skill set more than once. Most recently, he left the food industry to join the Sōrse startup. Five years in, he’s loving it. “We are in a sense transforming an industry,” he says. “We’re applying technology in an area it wasn’t applied in before, and it’s making a difference.”

Riefler spent two decades early in his career working in the aerospace industry before deciding that it was no longer a fit and moving into a series of leadership roles at TIC Gums.

“I left the aerospace industry as more and more of my work was going into war machines—equipment to kill people,” he says. “And that, more and more, started to bother me. So I made it my personal choice to change industries.”

For Rebecca Milczarek, the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a process of career reevaluation that led her halfway across the country to a completely different kind of job after she’d spent more than a decade as a research scientist in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Science (ARS) arm in Albany, Calif.

When her ARS job responsibilities shifted during COVID to focus more on writing research articles and preparing grant applications than on doing bench laboratory work, she found that she wasn’t itching to get back into the lab. That got her thinking about exploring new options.

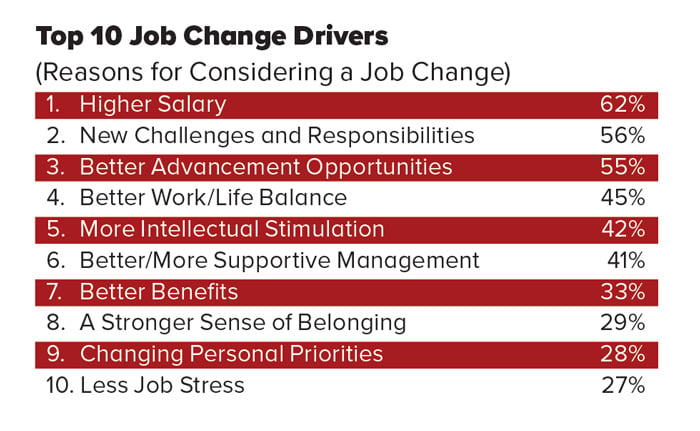

Top 10 Job Change Drivers (Reasons for Considering a Job Change)

Tapping into resources from Free the PhD introduced Milczarek to the research development field. She ultimately found a position as assistant director of research development at the University of Illinois Chicago that met her goals for both a career switch and a geographic shift that allows her to live near extended family members in the Midwest.

Envisioning the Future

A quarter (25%) of respondents in the IFT Employment and Salary Survey conducted this past February said they had made or considered a job change in the past 24 months.

When asked about the factors that would motivate them to change jobs, salary topped the list, followed by new challenges and responsibilities.

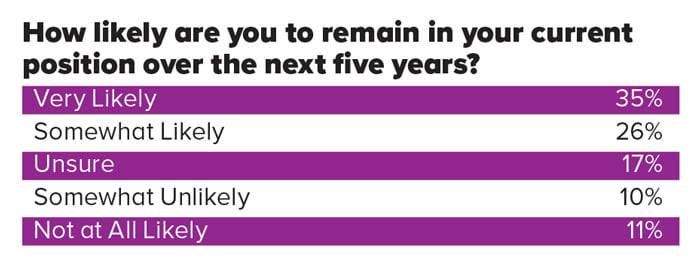

Career Path Survey findings present a mostly stable employment environment, however. Asked how likely they were to remain in their current position, 61% said staying put was very or somewhat likely. And just 14% of Career Path Survey respondents said they expected to transfer their skills to another professional sector.

Wilson of Nestlé Canada is among those who don’t anticipate making a change. “To be honest,” she says, “I’ve had several offers, which I’ve turned down because [Nestlé Canada] supported me in terms of my education, my growth. I was able to finish my master’s in global food law with Michigan State University, online.”

How likely are you to remain in your current position over the next five years?

What’s more, Wilson, notes, the company also provides opportunities for team members to work outside their assigned areas, which is a helpful professional growth vehicle. “So it’s not like, ‘Oh, you’re going to be stuck here until you retire,’” she observes.

Overall, employment in the science of food professions has been a positive experience for the majority of survey respondents. Asked to rate the likelihood of recommending a career in food science to their peers on a scale of 0 to 10, more than half (52%) responded with a score of 9 or 10.

Entrepreneurial Ambitions—or Not?

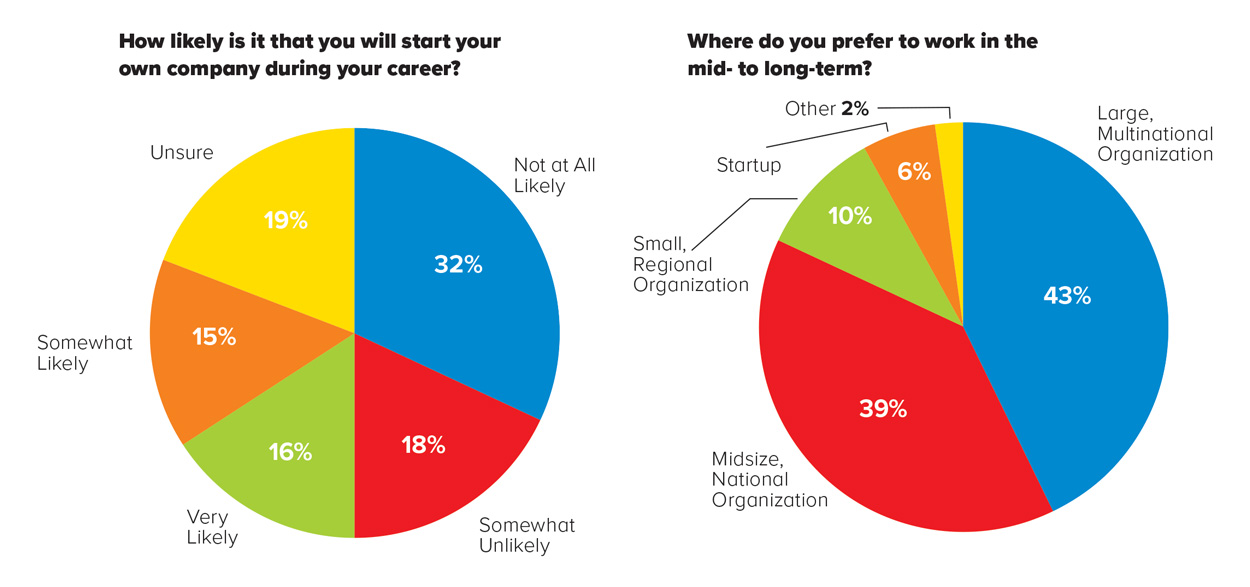

The startup life has some appeal for many, although half (50%) of Career Path Survey respondents say it’s unlikely that they will start their own company. Just 16% consider it very likely.

Working for a large, multinational corporation gets the most votes as a preferred workplace, followed by midsize/national, with only 6% of respondents saying that in the mid- to long-term they prefer to work for a startup. So despite the luster surrounding entrepreneurship, it seems that science of food professionals have a pretty strong comfort level with the corporate world.

How likely is it that you will start your own company during your career? (Left)

Where do you prefer to work in the mid- to long-term? (right)

Carlos Barroso has done both. He’s been an R&D-focused senior vice president at Campbell Soup Co. and PepsiCo, and two years ago he cofounded Plantasia Foods, a maker of plant-based meals.

“I don’t think there are many people that have gone from C-suite to entrepreneur back to the C-Suite and back to entrepreneur,” says Barroso, who also founded his own consulting firm.

Stepping away from the corporate life has its advantages, Barroso acknowledges. “As an entrepreneur and consultant, I enjoy impacting a wide range of organizations and giving them the benefits of my experiences—both successes and failures,” he says. “I also enjoy not spending an inordinate amount of my time in meetings that are not directly involved with my priorities.”

Side Gigs

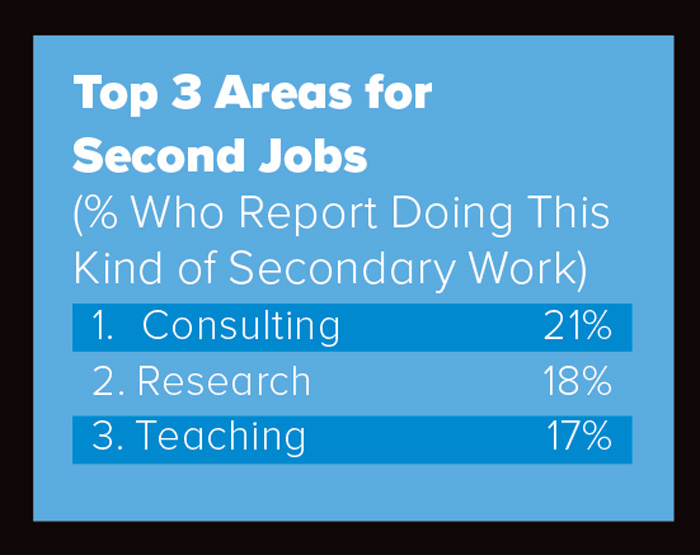

Top 3 Areas for Second Jobs

Four out of 10 survey respondents (40%) report having a second job. The most common side jobs include consulting, reported by 21%; research, cited by 18%; and teaching, noted by 17%. Other paid professional activities mentioned by survey participants include mentoring/coaching, serving on boards, editorial/writing services, food safety auditing, and training.

Academics are most likely to report a side gig; 80% said they had one. It is much less common in industry, with just over one-quarter (26%) reporting a secondary source of income.

Sixty-one percent of those who work as consultants say they directly influence, recommend, and/or specify in support of client decisions on ingredients and/or services (laboratory, food safety, and logistics). Half (50%) say they influence decisions related to equipment.

© Dmitrii_Guzhanin/Getty Images Plus

Navigating Roadblocks

The Career Path Survey asked respondents about barriers to success related to race, gender, and sexual orientation. Many respondents had compelling stories to tell. To learn about some of the experiences they shared in conversations with Food Technology editors and see what the survey showed, visit iftexclusives.org/career-barriers.

How the Survey Was Done

The IFT Career Path Survey was distributed by email by a private consulting firm and via links disseminated by individuals and organizations within the food community. The survey went to 29,300 members and non-members of IFT and drew about 3,000 responses. The margin of error is 2%.

To Learn More

A comprehensive report detailing findings from both the IFT Career Path Survey and the IFT Employment and Salary Survey is available free of charge to IFT members and is also offered for purchase by non-members. Please visit here to access the report.

Hero Image: © fona2/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Authors

-

Mary Ellen Kuhn Executive Editor

Mary Ellen Kuhn, executive editor and assistant director of publications, oversees the editorial content of Food Technology magazine.

-

Mary Ellen Kuhn, Kelly Hensel, Julie Larson Bricher, Emily Little

Categories

-

Food Sciences

-

Career Development

-

Professional Development

-

Career Resource

-

Salary Survey

-

Food Technology Magazine