Foodservice Picks Up the Pieces

The pandemic hit the U.S. foodservice industry unevenly and battered a vital innovation pipeline. How will its recovery impact menu and product development?

Article Content

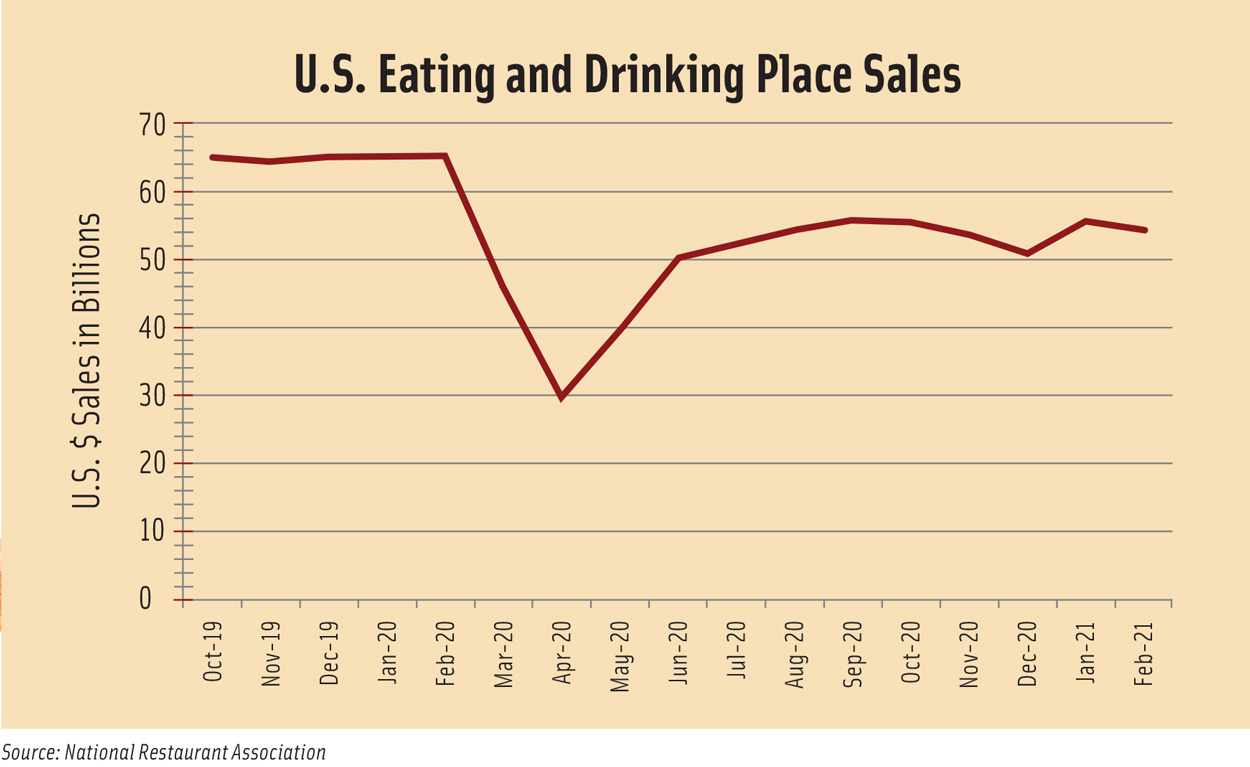

As the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the world last year, government mitigation measures limiting social gatherings placed the bullseye squarely on foodservice establishments. With dining rooms closed and consumers stuck at home, U.S. foodservice sales plummeted from $65 billion in February 2020 to $30 billion in April, according to the National Restaurant Association (NRA). (See the table on this page for a month-by-month look at the impact.) “Of all the industries in America, restaurants were the most severely impacted in terms of employment and sales declines,” says Hudson Riehle, NRA senior vice president, Research & Knowledge Group.

Inequities Magnified

As the pandemic extended into the summer, a K-shaped recovery emerged, with wildly diverging performance in different parts of the U.S. economy. While all foodservice categories felt the sting, some limited-service operations, like Chipotle and McDonald’s, were able to recover more quickly thanks in part to a carryout-friendly operating model. On the other hand, large casual-dining chains, where sales were lagging prior to the pandemic, were on the verge of collapsing. In 2020, more than 10 chains, including California Pizza Kitchen and Ruby Tuesday, declared bankruptcy.

“No restaurateur in the world ... has been unaffected by the COVID-19 pandemic,” wrote Jim Hyatt, CEO of California Pizza Kitchen in the company’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing. “For many restaurants, the COVID-19 pandemic will be the greatest challenge they will ever face; for some, it may also be their last.”

Foodservice workers and independently owned restaurants have been hardest hit by the pandemic. Before 2020, the United States boasted around 370,000 independent restaurants, representing 57% of total restaurants, according to Morgan Stanley. “These businesses support local economies and according to some studies, restaurants pump as much as 60% of their money back into their local communities,” says Kristopher Moon, chief operating officer at the James Beard Foundation. Black and Latino workers, disproportionately employed in low-paying foodservice jobs, were most affected when half of the 12.3 million–strong workforce was laid off in April 2020, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The Innovation Pipeline

What impact will this loss have on the larger foodservice industry?

“I think there will be significant repercussions, certainly in the short term and definitely for the midterm,” says Maeve Webster, president at foodservice consultancy Menu Matters. “For the short term what we’re looking at, essentially, is a loss of the engine that drives true innovation. And by that, I mean the innovation where you’re introducing completely new ingredients, completely new formats, and completely new cuisines.”

“Independent restaurants are the innovators,” and regional and national chains look to them “for trend direction and inspiration,” asserts Rob Corliss, chef/founder at All Things Epicurean.

New ingredients and flavors developed by fine-dining chefs and mixologists typically trickle down to limited-service chains and are incorporated into consumer packaged goods found on grocery store shelves. But the pandemic has shaken things up, and food and beverage manufacturers aren’t waiting for innovation to come to them. “We’re going to see incredible amounts of innovation at the retail level as manufacturers and retailers realize there is a gap and that there is an opportunity for them to fill some of that pent-up demand and some of the loss,” Webster says.

She sees an opportunity for retailers to enhance their prepared food offerings—deli, bakery, etc.—to meet consumers’ need for fresh, ready-to-eat food to take home. She believes fast-casual and fast-food chains also have an opportunity to fill the gap.

“Chains are more mass market by their nature, so their innovation will be a bit closer in,” says Webster. “But I think you will see chains reaching a bit further out than they used to because there is that opportunity. Still, it won’t be that super cutting-edge innovation that we’ve seen in the past.”

Foodservice operators are running leaner than ever, so ideating new dishes and creative concepts may leave them stretched thin. That is where, according to Webster, food scientists and product developers come in.

“I think for the food scientists, now is really going to be their time to shine because there’s going to be a much heavier leaning across the entire foodservice industry on value-added products,” predicts Webster. “From the value-added products that help operators build up a semi-scratch product to the value-added products that are virtually done and they’re just finishing them off—it will span the entire range.” Products like these will be important to struggling independent restaurants whose operators are hesitant to invest heavily in fresh food after getting shut down repeatedly during the pandemic, leaving them with no diners and extra inventory.

Off-Premise Optimization

Expect operators to be asking manufacturing suppliers for new ingredients and value-added products that help optimize shelf life and reduce labor from their dishes in order to meet continuing consumer demand for off-premise dining.

Even pre-pandemic, more than 60% of restaurant traffic was off premises, according to the NRA’s Riehle. “As the pandemic unfolded, in the second quarter and into the beginning of the third quarter, that proportion went up to almost 90%,” says Riehle. Earlier this spring, that number had gone back down slightly to the low 80% range. “As the consumer starts feeling more safe and secure in their ability to step up their on-site patronage, that number will continue to drop somewhat, but it certainly will not be going back to that pre-pandemic level any time soon,” Riehle predicts.

While most of the quick-service segment was custom built for the off-premise diner, the fine-dining and casual-dining restaurants had to pivot quickly—and sometimes awkwardly—to adapt. It required adopting digital technology for ordering, working with third-party delivery companies, rethinking menus, figuring out packaging, and marketing to consumers. And to stay in business, it meant doing it all as quickly as possible. Many were successful; in fact, according to Technomic, in the first month of the pandemic, 42% of restaurants added curbside pickup, 27% added delivery, and 26% added takeout.

But being successful at off-premise dining is more than putting food in a Styrofoam container, slapping some branding on it, and sending it on its way. Consumers quickly came to expect much more from their takeout and delivery. “If we were preteens when it came to our experience with delivery before Coronavirus, we’re now essentially in our early 30s within a 12-month period,” says Webster. “I think the at-home occasion is really going to remain a far more significant part of what dining from a restaurant actually means, and so that experience needs to be something more than what people were willing to put up with before.”

Reengineering the Menu

Some fine-dining innovators quickly saw the importance of mixing it up. Instead of trying to recreate its elaborate and experiential tasting menu for at-home dining, for example, Chicago’s three-star Michelin restaurant Alinea launched Alinea To Go. For less than $50 per person, customers can order a set three-course dinner with options like beef Wellington and mashed potatoes complete with instructions for reheating or finishing off the dishes at home.

While Alinea had to reconceptualize its entire business model, the shift for most foodservice operators was more centered on examining their menus and rethinking the dishes to optimize them for travel. For many, this also meant reducing the number of items it offers. “Innovation may also come in the form of skillfully reengineering the menu,” explains Corliss. “Restaurants are streamlining menus to maximize SKUs, minimize inventory, and make ordering more efficient and convenient for guests.”

Even fast-food mainstays like Taco Bell were forced to streamline. Taco Bell eliminated more than 10 items from its menu to “ensure an easy and fast ordering experience for our guests and team members, while simultaneously opening up opportunities for even more innovation,” according to a July press release. The casual-dining burger chain Red Robin cut its menu down to one-third of its pre-pandemic size, saving $2 million on labor and waste. Meanwhile, Denny’s replaced its entire menu with one that was 25% smaller and featured comfort dishes and items that travel well.

“There might be items that simply, no matter how you try and reengineer them, no matter how you try to deconstruct them or build them back, they’ll never travel well,” states Webster. She suggests either eliminating those dishes entirely or making them available for dine-in only. Bottom line: the off-premise menu must deliver the same quality as the dine-in food experience.

Packaging Becomes Critical

In addition to engineering menu items by substituting components, paring down elements, and incorporating value-added ingredients to enhance shelf life, operators need to consider delivery and takeout packaging. “Virtually every menu has items that travel well if the operator really thinks about how to pack them, the kind of material they need to legitimately protect the integrity of that product,” says Webster.

The surge in takeout and delivery in March and April 2020 spurred many operators and packaging manufacturers to create new solutions. “There’s a whole host of innovation going on now in off-premise packaging,” says Riehle. According to the NRA’s 2021 State of the Restaurant Industry report, a solid majority of operators—including 86% of fine-dining operators—say they have upgraded their takeout and delivery packaging since March 2020.

Vented and compartmentalized containers continue to be in demand to keep food elements from getting soggy and enable the guest to reconstruct the item at home. A burger packaged in a paper envelope does little to prevent sogginess from setting in during transit, for example, while a compartmentalized container that keeps condiments, bun, and burger separate prevents a mushy final product. Today, as operators struggle to stay afloat and consumers demand more in terms of quality, if an order arrives soggy or cold, the business risks losing a customer for good.

“I think one of the big changes that we’ve seen overall from a consumer’s expectation standpoint is that if you can’t give it to me in a restaurant, I want it the same way when it’s delivered or if I’m picking it up or taking it away,” says Technomic’s Joseph Pawlak.

The flavor and quality of the food will always remain the No. 1 priority for consumers. But selecting the appropriate packaging extends beyond this primary need—it can also communicate the quality of the brand. “Packaging should correlate to the style of your food,” contends Corliss. “Meaning, an upscale establishment that is now temporarily transitioning their nonexistent dine-in menu to an off-premise model needs to ensure that the style of packaging fits the caliber of their menu offerings.”

Additionally, as consumers began ordering more delivery and takeout, their awareness of the amount of packaging waste and its impact on the environment grew. Not every operation is going to have the need or the ability to prioritize sustainable packaging, but if it is something that is important to a restaurant’s core demographic, it should be considered. “Determine if it is logistically and financially feasible for your operation to implement sustainable packaging,” says Corliss. “If so, craft that packaging story alongside the story behind your food—they go hand in hand.”

Post-Pandemic Outlook

Food and beverage establishments have gone through the wringer in 2020. And while most survived, Technomic estimates that 8% of U.S. restaurants closed in 2020. Those remaining will continue to struggle until a large percentage of the public receives vaccinations and feels comfortable—both psychologically and financially—with visiting dining establishments more regularly.

“The industry was down last year pretty dramatically—about 26% from what it was in 2019,” reports Pawlak. “This year will be better, but it’s going to be a few years before we are totally back.” In fact, Technomic forecasts that total foodservice sales won’t return to pre-pandemic (2019) levels until 2023. Limited-service restaurants will recover at a faster pace, reaching 2019 sales levels in 2022, while full-service restaurants won’t see a full recovery until 2025. In terms of employment, the NRA reports that the United States ended this past year 2.5 million jobs below its pre-COVID level.

“It’s important to look at 2021 as a year of transition and redevelopment for the industry,” says Riehle. “As employment comes back, incomes come back, and consumers re-patronize on-site, it still is definitely quite a positive future over the longer term for the industry.”

The pandemic laid bare some systemic issues in the foodservice industry while also accelerating innovations that will grow the industry for years to come. COVID-19 forced the industry to adopt new technologies, such as digital ordering and back-of-house automation, and to explore new business models, such as ghost kitchens and virtual brands. The industry has come to realize that adopting new technologies is not only necessary to compete and survive, but it can also strengthen customer relationships while generating valuable data that operators can use to refine offerings and make smart business decisions.

“I am confident restaurants will continue to meet challenges and evolve,” says Corliss. “It most likely won’t be easy, but resiliency is our backbone.”

Pawlak agrees. “Longer term, we are going to get more independents coming back,” he says. “We are going to repopulate, regenerate, and the industry will thrive again.”

.jpg?mw=500&hash=D1E2E8B94FED0CCA2F5CEA8243FD787B)