Biomilq: Still in Its Infancy, Already Poised to Disrupt

Startups & Innovators | INNOVATIONS

Shazi Visram knows a thing or two about starting up a food company and making it successful. So when the founder of Happy Family Organics became one of the earliest angel investors in Biomilq in early 2020, Michelle Egger was encouraged by the capital infusion—and by Visram’s advice.

“She was one of the first people in our seed round who urged us to stick with our valuation and dictate our terms,” says Egger, co-founder with Leila Strickland of mammary biotechnology startup Biomilq. Visram, who sold her better-for-you children’s food company to Groupe Danone in 2013, told us to “show up confidently with the technology we had and [to be] clear about what we need” and that “we are not a beggar and not Oliver Twist,” Egger recalls.

That Visram is a woman also reminded Egger and Strickland of an unpleasant reality: Female entrepreneurs remain underrepresented in the food-and-beverage space so far, for various reasons. “They get set up to believe that they have to bend and be the ones that are malleable,” Egger says. “They may be willing to take whatever they can to get cash.”

Funding for Female Founders

Overall, venture capital investment in the food business is “getting a little better for women and minorities, but it’s a slow crawl to reach equality,” says Hillary Hughes, chair of the food and beverage practice for the Foster Garvey law firm. The gender balance isn’t getting any help from the fact that many food startups now have a digital component, where male-dominated Silicon Valley can be a huge factor, she says.

For female entrepreneurs, “the path to get capital isn’t a well-worn path,” contends Adam Demuyakor, founder and managing partner of Wilshire Lane Capital, which has funded two woman-led food delivery startups.

But Biomilq has access to capital. The company recently closed a $21 million Series A financing round led by Danish life science investor Novo Holdings and clean tech financier Breakthrough Energy Ventures, the latter of which was founded by a who’s who of high-profile billionaires: Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Richard Branson, Alibaba founder Jack Ma, Michael Bloomberg, and Mark Zuckerberg.

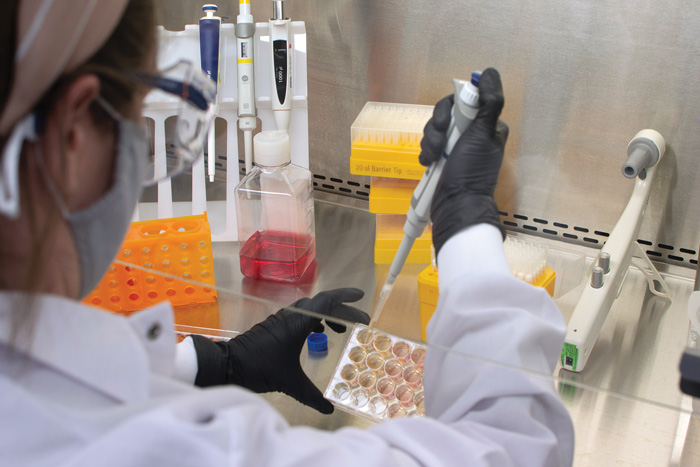

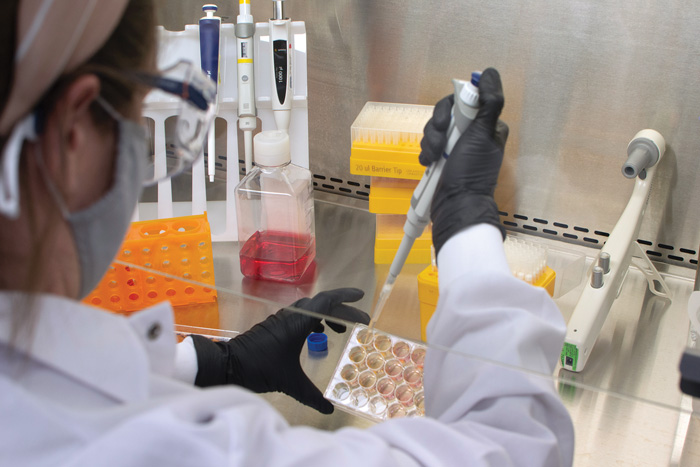

Some of the world’s savviest entrepreneurs are excited about Biomilq because the company has synthesized a breast milk alternative that it is ready to commercialize within four years. It is made from cultured human mammary epithelial cells, so Biomilq calls it “human milk produced outside the body.” Biomilq claims it can produce both casein and lactose, which are important proteins in real human breast milk, and to be a pioneer in producing additional integral components of milk within the same system, using an approach that is sterile throughout.

“We’re building a pilot plant now in North Carolina for high enough quantities that we can enter safety testing,” Egger says. “That’s an important milestone and goal for us. From there, we’re working on process design to be able to scale. And in the next two to three years we’ll have a product we’ll be able to prove is safe and of high quality and nourishes the human body.”

Some of Biomilq’s signature backers also have been busy funding other would-be disruptors of the animal protein business, including plant-based alt-meat makers Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods and cell-cultured meat company Upside Foods. Egger and Strickland share their billionaire investors’ ambition to phase out animal products to reduce the carbon footprint.

Ambitions, Potential, Hurdles

In Biomilq’s case, the competition includes not only moms’ breast milk but also, of course, dairy-based infant formula, part of a total $100 billion worldwide infant formula market. “Parents shouldn’t have to decide between feeding their kids and doing what’s best for the planet,” Egger says.

But there’s even more to Biomilq’s ambitions. “All mammalian life on the planet is supported by mammary cells,” Egger says. “So as you think about the broader animal kingdom, there is so much we don’t know and don’t best utilize. There are potentially huge implications for human health and development outside breast or cow’s milk.”

Many large companies are tracking Biomilq’s progress, Egger says, precisely because its technology may have broad implications. “Everyone is interested,” she says. “Not just formula producers or even dairy production companies, but also amazing numbers of technologically advanced food and personal product companies that are really intrigued because, frankly, human milk has evolved to have so much benefit for the human body, but we haven’t fully utilized the potential for the infant and even beyond.”

Many obstacles remain before parents might be able to purchase synthetic Biomilq the way they do infant formula. They include the fact that Biomilq technology is borrowed from expensive pharmaceutical manufacturing processes, not from the food industry. The challenge is new to Egger, a food scientist with a degree from Purdue University. She worked in product development at General Mills for most of her career and then at the Gates Foundation. Strickland was a cell biologist.

“The equipment design and costs for biologics make for an interesting challenge, compared with milk,” Egger says. “The price point from pharma manufacturing doesn’t match up with the downstream price we’ll have to hit to be an accessible product.”

The hybrid nature of a breast milk substitute—anchored in both food and medicine—also makes it difficult for Biomilq to find “expertise from the ranks of two industries that often don’t intermix.” What her company is doing is “pretty far outside of what innovation looks like in food,” Egger says. “We have these category shifts, which make generational shifts, and so classically trained food scientists and engineers are going to have to do new tricks.”

Biomilq also faces competition from at least one other startup, Turtle Tree Labs, based in Singapore. This company also aims to create a human milk replacement derived from cell-based technology and also has attracted big-name investors.

What Will Moms Think?

But Biomilq’s biggest challenge may be gaining acceptance among its target customers, whatever the product’s environmental bona fides. There’s a unique challenge in proposing to replace something as developmentally and culturally bound as “mother’s milk.” Breast milk is a rich source of maternal genetic information and a key in developing infant immune systems, and there’s no indication Biomilq could address that. Also, variability in real breast milk influences neonatal outcomes.

What’s more, even if meat eaters eventually accept synthesized, plant-based, or cultured substitutes for real meat on the basis of taste, texture, nutrition, and the sustainability quotient—not to mention price—would that willingness necessarily translate into a casual acceptance of artificial breast milk? They’d be feeding their children, after all, not themselves.

Egger acknowledges such realities, saying, “food beliefs are deeply ingrained and held.” But she notes that “societally, we sometimes have skewered technologies in the past that we now rely on heavily.”

In any event, Egger and Strickland seem already to have moved their fledgling company beyond the boundaries of gender-based barriers. One reason might be how big their idea is and how well they’ve proven it so far.

“If you’re doing something that’s so innovative or cutting-edge that it’s going to disrupt or transform a category, VCs like that sort of thing, and the money generally will come regardless of the founder profile,” Hughes says. “An implicit gender bias doesn’t trump potentially really big financial returns.”